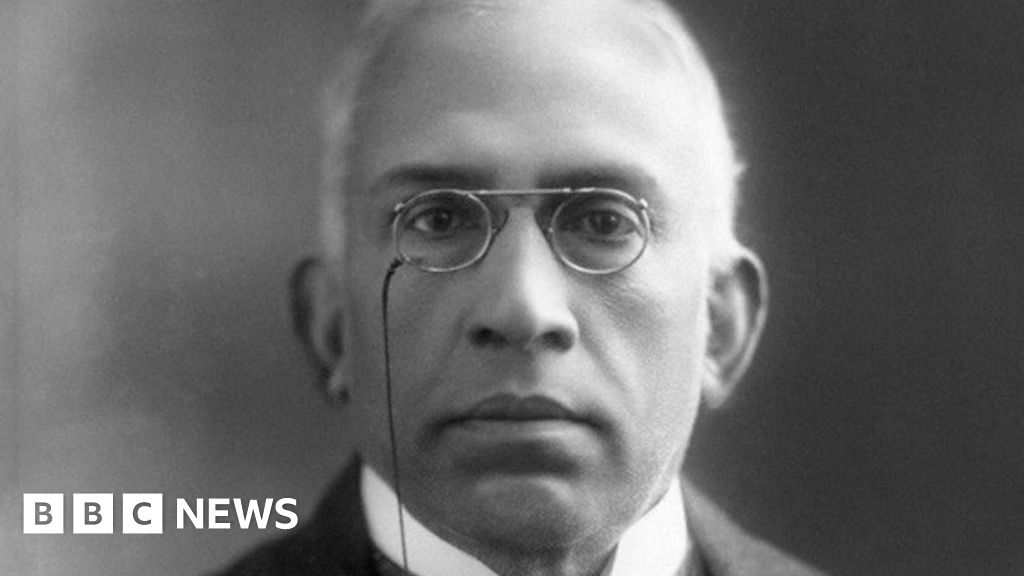

Long before India gained independence, one defiant voice inside the British Empire dared to call out a colonial massacre - and paid a price for it. Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair, a lawyer, was one of the few Indians to be appointed to top government posts when the British ruled the country. In 1919, he resigned from the Viceroy's Council after the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in the northern Indian city of Amritsar in Punjab, in which hundreds of civilians attending a public meeting were shot dead by British troops. On the 100th anniversary of the massacre, then UK Prime Minister Theresa Maydescribed the tragedy as a "shameful scar"on Britain's history in India. Nair's criticism of Punjab's then Lieutenant Governor, Michael O'Dwyer, led to a libel case against him, which helped spotlight the massacre and the actions of British officials. In a biography of Nair, KPS Menon, independent India's first foreign secretary, described him as "a very controversial figure of his time". Nair was known for his independent views and distaste for extremist politics, and spoke critically of colonial rule and even of Mahatma Gandhi, the Indian independence hero who is now regarded as the father of the nation. Menon, who married Nair's daughter Saraswathy, wrote: "Only [Nair] could have insulted the all powerful British Viceroy on his face and opposed Mahatma Gandhi openly." Nair was not a familiar name in India in recent decades, but earlier this year, a Bollywood film based on the court case, Kesari Chapter 2- starring superstar Akshay Kumar - helped bring attention to his life. Nair was born in 1857 into a wealthy family in what is now Palakkad district in Kerala state. He studied at the Presidency College in Madras, acquiring a bachelor's degree before studying law and beginning his career as an apprentice with a Madras High Court judge. In 1887, he joined the social reform movement in the Madras presidency. Throughout his career, he fought to reform Hindu laws of the time on marriage and women's rights and to abolish the caste system. For some years, he was a delegate to the Indian National Congress and presided over its 1897 session in Amraoti (Amravati). In his address, he held the British-run government "morally responsible for the extreme poverty of the masses", saying the annual famines "claimed more victims and created more distress than under any civilised government anywhere else in the world". He was appointed public prosecutor in 1899 and writes in his autobiography about advising the government on seditious articles in newspapers, including those by his close friend G Subramania Iyer, the first editor of The Hindu newspaper. "On many occasions… I was able to persuade them not to take any step against him." He became a high court judge in 1908 and was knighted four years later. Nair moved to Delhi in 1915 when he was appointed a member of the Viceroy's Council, only the third Indian to hold the position. He was a fierce proponent of India's right to govern itself and pushed for constitutional reforms during his time on the council. Through 1918 and 1919, his dissent and negotiations with Edwin Montagu, then secretary of state for India, helped expand provisions of the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms which laid out how India would gradually achieve self-governance. Montagu wrote in his diary that he had been warned "that it was absolutely necessary to get him on my side, for Sankaran Nair wielded more influence than any other Indian". A pivotal moment in Nair's career as a statesman was the massacre in Jallianwala Bagh, when hundreds of unarmed Indians were shot dead in a public garden on the day of the Baisakhi festival. Official estimates said nearly 400 people were killed and more than 1,500 wounded by the soldiers, who fired under the orders of Brigadier General REH Dyer. Indian sources put the death toll closer to 1,000. Nair writes in his 1922 book Gandhi and Anarchy about following the events in Punjab with increasing concern. The shooting at Jallianwala Bagh was part of a larger crackdown in the province, where martial law had been introduced - the region was cut off from the rest of the country and no newspapers were allowed into it. "If to govern the country, it is necessary that innocent persons should be slaughtered at Jallianwala Bagh and that any Civilian Officer may, at any time, call in the military and the two together may butcher the people as at Jallianwala Bagh, the country is not worth living in," he wrote. A month later, he resigned from the council and left for Britain, where he hoped to rouse public opinion on the massacre. In his memoir, Nair writes of speaking to the editor of The Westminster Gazette which soon published an article called the Amritsar Massacre. Other papers including The Times also followed suit. "Worse things had happened under British rule, but I am glad I was able to obtain publicity for this one at least," Nair wrote. Nair's book Gandhi and Anarchy drew the ire of several Indian nationalists of the time after he criticised Gandhi's civil disobedience movement, calling it a "weapon to be used when constitutional methods have failed to achieve our purpose". But it was the few passages condemning Sir Michael O'Dwyer, the Lieutenant Governor of Punjab, that became the basis for the libel suit against him in 1924. Nair accused O'Dwyer of terrorism, holding him responsible for the atrocities committed by the civil government before the imposition of martial law. A five-week trial in the Court of King's Bench in London ruled 11:1 in favour of O'Dwyer, awarding damages of £500 and £7,000 in costs to him. O'Dwyer offered to forgo this for an apology but Nair refused and paid instead. Reports of the depositions in the hearing were published daily in The Times. Nair's family says despite losing, the case achieved his purpose of having the atrocities brought to public attention. Nair's great-grandson Raghu Palat, who co-wrote the book The Case That Shook the Empire, with his wife Pushpa, says the case helped spark "an uproar for the freedom movement". It also showed that "there was no point in having a dominion status under the empire when the British cannot be expected to deal with their subjects fairly", adds Pushpa. Even Gandhi referred to the case several times, writing once that Nair had showed pluck in fighting without hope of victory, historian PC Roy Chaudhury later pointed out. After losing the case, Nair continued with his career in India. He was chairman of the Indian Committee of the Simon Commission, which reviewed the working of constitutional reforms in India in 1928. He died in 1934 at the age of 77. Through his career, Menon notes, Nair "bent all his thoughts and energies on the emancipation of his country from the bondage of foreign domination and native custom. In this task, he achieved as much success as any man, wedded to constitutional methods".

The Indian who called out a massacre - and shamed the British Empire

TruthLens AI Suggested Headline:

"Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair's Legacy in Challenging British Colonial Atrocities"

TruthLens AI Summary

Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair, a prominent lawyer and one of the few Indians appointed to high government positions during British rule, became a pivotal figure in calling out the atrocities committed by colonial authorities, particularly following the infamous Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919. This tragic event saw British troops open fire on unarmed civilians in Amritsar, resulting in hundreds of deaths and injuries. Nair's resignation from the Viceroy's Council in protest against the massacre and his subsequent criticism of Punjab's Lieutenant Governor, Michael O'Dwyer, led to a libel case that highlighted the brutal realities of colonial rule. His outspoken views and willingness to challenge both British officials and Indian leaders like Mahatma Gandhi marked him as a controversial yet significant voice in the struggle for Indian self-governance. KPS Menon, the first foreign secretary of independent India, noted Nair's unique ability to confront powerful figures, demonstrating his commitment to social reform and justice.

Nair's career was characterized by his advocacy for constitutional reforms and his deep engagement in social issues, including the rights of women and the abolition of the caste system. He was instrumental in the Indian National Congress and played a significant role in shaping public discourse around India's governance. Following the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, Nair traveled to Britain to raise awareness of the incident, leading to widespread media coverage and public outcry. Although he lost the libel case against O'Dwyer, the proceedings brought significant attention to the issues of colonial oppression and sparked conversations that contributed to the Indian independence movement. Nair's later work included serving as the chairman of the Indian Committee of the Simon Commission, which evaluated constitutional reforms in India. His legacy is marked by his relentless pursuit of justice and his dedication to the cause of Indian emancipation from colonial rule, as noted by historians and family members alike, who recognize his contributions to the fight for India's independence.

TruthLens AI Analysis

You need to be a member to generate the AI analysis for this article.

Log In to Generate AnalysisNot a member yet? Register for free.