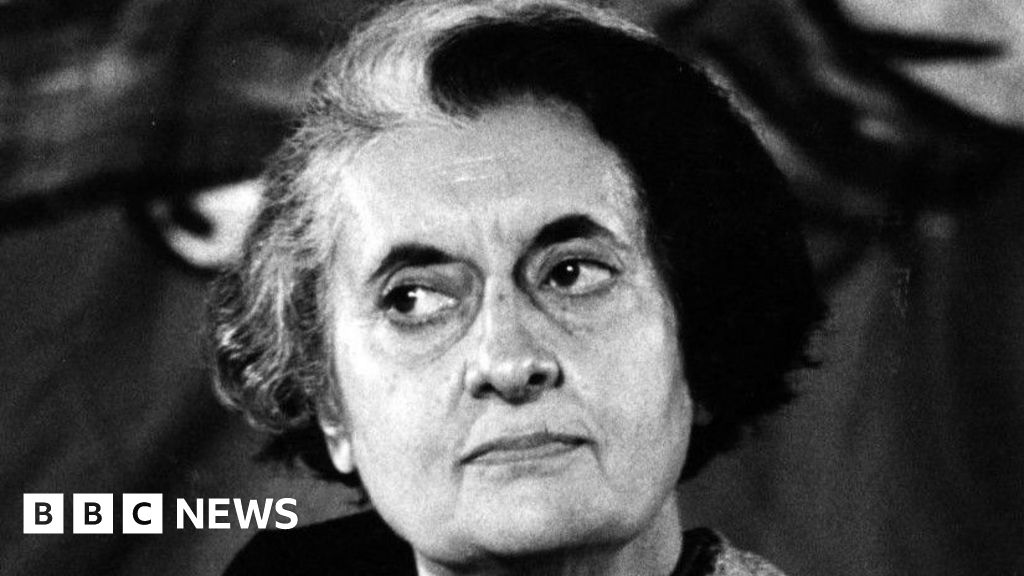

During the mid-1970s, under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi's imposition of the Emergency, India entered a period where civil liberties were suspended and much of the political opposition was jailed. Behind this authoritarian curtain, her Congress party government quietly began reimagining the country - not as a democracy rooted in checks and balances, but as a centralised state governed by command and control, historian Srinath Raghavan reveals in his new book. In Indira Gandhi and the Years That Transformed India, Prof Raghavan shows how Gandhi's top bureaucrats and party loyalists began pushing for a presidential system - one that would centralise executive power, sideline an "obstructionist" judiciary and reduce parliament to a symbolic chorus. Inspired in part by Charles de Gaulle'sFrance, the push for a stronger presidency in India reflected a clear ambition to move beyond the constraints of parliamentary democracy - even if it never fully materialised. It all began, writes Prof Raghavan, in September 1975, when BK Nehru, a seasoned diplomat and a close aide of Gandhi, wrote a letter hailing the Emergency as a "tour de force of immense courage and power produced by popular support" and urged Gandhi to seize the moment. Parliamentary democracy had "not been able to provide the answer to our needs", Nehru wrote. In this system the executive was continuously dependent on the support of an elected legislature "which is looking for popularity and stops any unpleasant measure". What India needed, Nehru said, was a directly elected president - freed from parliamentary dependence and capable of taking "tough, unpleasant and unpopular decisions" in the national interest, Prof Raghavan writes. The model he pointed to was de Gaulle's France - concentrating power in a strong presidency. Nehru imagined a single, seven-year presidential term, proportional representation in Parliament and state legislatures, a judiciary with curtailed powers and a press reined in by strict libel laws. He even proposed stripping fundamental rights - right to equality or freedom of speech, for example - of their justiciability. Nehru urged Indira Gandhi to "make these fundamental changes in the Constitution now when you have two-thirds majority". His ideas were "received with rapture" by the prime minister's secretary PN Dhar. Gandhi then gave Nehru approval to discuss these ideas with her party leaders but said "very clearly and emphatically" that he should not convey the impression that they had the stamp of her approval. Prof Raghavan writes that the ideas met with enthusiastic support from senior Congress leaders like Jagjivan Ram and foreign minister Swaran Singh. The chief minister of Haryana state was blunt: "Get rid of this election nonsense. If you ask me just make our sister [Indira Gandhi] President for life and there's no need to do anything else". M Karunanidhi of Tamil Nadu – one of two non-Congress chief ministers consulted - was unimpressed. When Nehru reported back to Gandhi, she remained non-committal, Prof Raghavan writes. She instructed her closest aides to explore the proposals further. What emerged was a document titled "A Fresh Look at Our Constitution: Some suggestions", drafted in secrecy and circulated among trusted advisors. It proposed a president with powers greater than even their American counterpart, including control over judicial appointments and legislation. A new "Superior Council of Judiciary", chaired by the president, would interpret "laws and the Constitution" - effectively neutering the Supreme Court. Gandhi sent this document to Dhar, who recognised it "twisted the Constitution in an ambiguously authoritarian direction". Congress president DK Barooah tested the waters by publicly calling for a "thorough re-examination" of the Constitution at the party's 1975 annual session. The idea never fully crystallised into a formal proposal. But its shadow loomed over theForty-second Amendment Act, passed in 1976, which expanded Parliament's powers, limited judicial review and further centralised executive authority. The amendment made striking down laws harder by requiring supermajorities of five or seven judges, and aimed to dilute the Constitution's'basic structure doctrine'that limited parliament's power. It also handed the federal government sweeping authority to deploy armed forces in states, declare region-specific Emergencies, and extend President's Rule - direct federal rule - from six months to a year. It also put election disputes out of the judiciary's reach. This was not yet a presidential system, but it carried its genetic imprint - a powerful executive, marginalised judiciary and weakened checks and balances. The Statesman newspaper warned that "by one sure stroke, the amendment tilts the constitutional balance in favour of the parliament." Meanwhile, Gandhi's loyalists were going all in. Defence minister Bansi Lal urged "lifelong power" for her as prime minister, while Congress members in the northern states of Haryana, Punjab, and Uttar Pradesh unanimously called for a new constituent assembly in October 1976. "The prime minister was taken aback. She decided to snub these moves and hasten the passage of the amendment bill in the parliament," writes Prof Raghavan. By December 1976, the bill had been passed by both houses of parliament and ratified by 13 state legislatures and signed into law by the president. After Gandhi's shock defeat in 1977, the short-lived Janata Party - a patchwork of anti-Gandhi forces - moved quickly to undo the damage. Through theForty-thirdandForty-fourthAmendments, it rolled back key parts of the Forty Second, scrapping authoritarian provisions and restoring democratic checks and balances. Gandhi was swept back to power in January 1980, after the Janata Party government collapsed due to internal divisions and leadership struggles. Curiously, two years later, prominent voices in the party again mooted the idea of a presidential system. In 1982, with President Sanjiva Reddy's term ending, Gandhi seriously considered stepping down as prime minister to become president of India. Her principal secretary later revealed she was "very serious" about the move. She was tired of carrying the Congress party on her back and saw the presidency as a way to deliver a "shock treatment to her party, thereby giving it a new stimulus". Ultimately, she backed down. Instead, she elevated Zail Singh, her loyal home minister, to the presidency. Despite serious flirtation, India never made the leap to a presidential system. Did Gandhi, a deeply tactical politician, hold herself back ? Or was there no national appetite for radical change and India's parliamentary system proved sticky? There was a hint of presidential drift in the early 1970s, as India's parliamentary democracy - especially after 1967 - grew more competitive and unstable, marked by fragile coalitions, according to Prof Raghavan. Around this time, voices began suggesting that a presidential system might suit India better. The Emergency became the moment when these ideas crystallised into serious political thinking. "The aim was to reshape the system in ways that immediately strengthened her hold on power. There was no grand long-term design - most of the lasting consequences of her [Gandhi's] rule were likely unintended," Prof Raghavan told the BBC. "During the Emergency, her primary goal was short-term: to shield her office from any challenge. The Forty Second Amendment was crafted to ensure that even the judiciary couldn't stand in her way." The itch for a presidential system within the Congress never quite faded. As late as April 1984, senior minister Vasant Sathe launched a nationwide debate advocating a shift to presidential governance - even while in power. But six months later, Indira Gandhi was assassinated by her Sikh bodyguards in Delhi, and with her, the conversation abruptly died. India stayed a parliamentary democracy.

The forgotten story of India's brush with presidential rule

TruthLens AI Suggested Headline:

"Exploring India's Historical Consideration of a Presidential System During the Emergency"

TruthLens AI Summary

In the mid-1970s, during a tumultuous period in Indian history marked by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi's imposition of the Emergency, the country experienced a significant curtailment of civil liberties and a severe crackdown on political opposition. Historian Srinath Raghavan, in his book 'Indira Gandhi and the Years That Transformed India', highlights how this authoritarian environment fostered ambitions within Gandhi's Congress party to shift towards a presidential system of governance. This shift was driven by influential bureaucrats and party loyalists who sought to centralize executive power and diminish the role of the judiciary and legislature. As early as September 1975, B.K. Nehru, a close aide to Gandhi, advocated for a directly elected president, arguing that the existing parliamentary system was inadequate for India's needs. He envisioned a strong presidency modeled after Charles de Gaulle's France, which would empower the executive to make decisive, albeit unpopular, choices without being impeded by legislative or judicial oversight. This idea garnered enthusiastic support from various Congress leaders, although it was met with skepticism by some, including non-Congress chief ministers.

As discussions progressed, a clandestine proposal emerged, suggesting extensive constitutional changes that would enable a president with expansive powers, potentially surpassing those of the American presidency. This proposal included a new council to interpret laws and a judiciary with significantly reduced authority, effectively undermining the Supreme Court's role. Although the push for a formal presidential system did not materialize, the ideas influenced the Forty-second Amendment Act of 1976, which expanded parliamentary powers and limited judicial review. The amendment raised concerns about the balance of power in Indian democracy, as it made significant changes to the Constitution that favored a powerful executive and restricted judicial independence. Following Gandhi's electoral defeat in 1977, the Janata Party sought to reverse these changes, restoring democratic checks and balances. Despite flirtations with the idea of a presidential system in the years that followed, particularly during Gandhi's second term, India ultimately remained a parliamentary democracy, reflecting both a lack of consensus on radical change and Gandhi's political calculations during her tenure.

TruthLens AI Analysis

The article delves into a significant yet often overlooked chapter in India's political history, focusing on the period during the Emergency imposed by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in the mid-1970s. It highlights the push for a presidential system that would centralize power and diminish the role of the judiciary and parliament, drawing parallels with Charles de Gaulle's France. The narrative suggests that this shift was not merely a political maneuver but a reflection of deeper ideological aspirations within the Congress party.

Historical Context and Political Implications

The author emphasizes the authoritarian nature of the Emergency, where civil liberties were curtailed and political dissent was harshly repressed. The discussion around a presidential system reveals an underlying ambition to redefine India’s governance structure away from the existing parliamentary democracy. This historical analysis may provoke readers to reflect on contemporary political dynamics, especially in relation to the current government’s approach to power and governance.

Public Perception and Potential Manipulation

The article likely aims to evoke a critical awareness among the public about the fragility of democratic institutions and the dangers of centralizing power. By highlighting this historical narrative, there may be an intention to caution against similar trends in the present. It subtly implies that the pursuit of a strong presidency, while appealing to some, could lead to authoritarianism. This aspect raises questions about what might be omitted from the discussion regarding the current political climate, potentially implying that similar tendencies are emerging today.

Trustworthiness and Reliability

The reliability of the article appears strong, as it draws on historical accounts and the scholarship of a historian, Srinath Raghavan. The use of documented evidence from the 1970s provides a solid foundation for the argument. However, the interpretation of these events and their implications can be subjective, which may lead to different conclusions based on the reader's perspective.

Connection with Other News

When compared to contemporary news narratives, this article connects with ongoing discussions about governance, democracy, and authority in India. It may resonate with reports on political centralization or challenges to judicial independence, suggesting a continuity of themes throughout India's political evolution.

Impact on Society and Economy

The implications of such a discussion could extend beyond historical reflection to influence current socio-political discourse. If the public perceives a trend toward authoritarian governance, it could spark debates about civil rights and democratic integrity, potentially affecting political activism and public trust in institutions.

Support Base and Audience

This article may resonate more with politically engaged communities, historians, and those concerned about democracy and civil liberties. It is likely to attract readers who are critical of government overreach and advocates for preserving democratic norms.

Global Perspective

From a global standpoint, the examination of India's political history in relation to centralized authority can contribute to broader discussions about democracy worldwide. It underscores the importance of vigilance against authoritarianism, an issue that remains relevant in many countries today.

In conclusion, the article sheds light on a critical moment in India's history, encouraging readers to reflect on the implications of centralizing power and the historical lessons it offers for contemporary governance. The analysis reveals a nuanced understanding of India's political landscape and its challenges, while also hinting at broader themes of democracy that resonate globally.