In a long-sought first, researchers have sequenced the entire genome of an ancient Egyptian person, revealing unprecedented insight about the ancestry of a man who lived during the time when the first pyramids were built.

The man, whose remains were found buried in a sealed clay pot in Nuwayrat, a village south of Cairo, lived sometime between 4,500 and 4,800 years ago, which makes his DNA the oldest ancient Egyptian sample yet extracted. The researchers concluded that 80% of his genetic material came from ancient people in North Africa while 20% traced back to people in West Asia and the Mesopotamia region.

Their findings, published Wednesday in the journalNature, offer new clues to suggest there were ancient cultural connections between ancient Egypt and societies within the Fertile Crescent, an area that includes modern-day Iraq (once known as Mesopotamia), Iran and Jordan. While scientists have suspected these connections, before now the only evidence for them was archaeological, rather than genetic.

The scientists also studied the man’s skeleton to determine more about his identity and found extensive evidence of hard labor over the course of a long life.

“Piecing together all the clues from this individual’s DNA, bones and teeth have allowed us to build a comprehensive picture,” said lead study author Dr. Adeline Morez Jacobs, visiting research fellow at England’s Liverpool John Moores University, in a statement. “We hope that future DNA samples from ancient Egypt can expand on when precisely this movement from West Asia started.”

Pottery and other artifacts have suggested that Egyptians may have traded goods and knowledge across neighboring regions, but genetic evidence of just how closely different ancient civilizations mingled has been harder to pin down because conditions such as heat and humidity quickly degrade DNA, according to the study authors. This man’s remains, however, were unusually well-preserved in their burial container, and the scientists were able to extract DNA from one of the skeleton’s teeth.

While the findings only capture the genetic background of one person, experts said additional work could help answer an enduring question about the ancestry of the first Egyptians who lived at the beginning of the longest-lasting known civilization.

Swedish geneticist Svante Pääbo, who won theNobel Prize in physiology or medicine in 2022for sequencing the first Neanderthal genome, madepioneering attempts40 years ago to extract and study DNA from ancient Egyptian remains, but he was unable to sequence a genome. Poor DNA preservation consistently posed an obstacle.

Since then, the genomes of three ancient Egyptian peoplehave been only partially sequencedby researchersusing “target-enriched sequencing” to focus on specific markers of interest in the specimens’ DNA. The remains used in that work date back to a more recent time in Egyptian history, from 787 BC to AD 23.

It was ultimately improvements in technology over the past decade that paved the way for the authors of the new study to finally sequence an entire ancient Egyptian genome.

“The technique we used for this study is generally referred to as ‘shotgun sequencing,’ which means we sequence all DNA molecules isolated from the teeth, giving us coverage across the whole genome,” wrote study coauthor Dr. Linus Girdland-Flink, a lecturer in biomolecular archaeology at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland, in an email. “Our approach means that any future researcher can access the whole genome we published to find additional information. This also means there is no need to return to this individual for additional sampling of bone or tooth material.”

The man, who died during a time of transition between Egypt’s Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom periods, was not mummified before burial because it was not yet standard practice — and that likely preserved his DNA, the researchers said.

“It may have been a lucky circumstance — perhaps we found the needle in the haystack,” Girdland-Flink said. “But I think we will see additional genomes published from ancient Egypt over the coming years, possibly from individuals buried in ceramic pots.”

While Egypt’s overall climate is hot, the region has relatively stable temperatures, a key factor for long-term genetic preservation, Girdland-Flink said. That climate, the clay pot used for burial and the rock tomb it was placed in all played a role in preventing the man’s DNA from deteriorating, he said.

For their analysis, the researchers took small samples of the root tips of one of the man’s teeth. They analyzed the cementum, a dental tissue that locks the teeth into the jaw, because it is an excellent tool for DNA preservation, Girdland-Flink said.

Of the seven DNA extracts taken from the tooth, two were preserved enough to be sequenced. Then, the scientists compared the ancient Egyptian genome with those of more than 3,000 modern people and 805 ancient individuals, according to the study authors.

Chemical signals called isotopes in the man’s tooth recorded information about the environment where he grew up and the diet he consumed as a child as his teeth grew. The results were consistent with a childhood spent in the hot, dry climate of the Nile Valley, consuming wheat, barley, animal protein and plants associated with Egypt.

But 20% of the man’s ancestry best matches older genomes from Mesopotamia, suggesting that the movement of people into Egypt at some point may have been fairly substantial, Girdland-Flink.

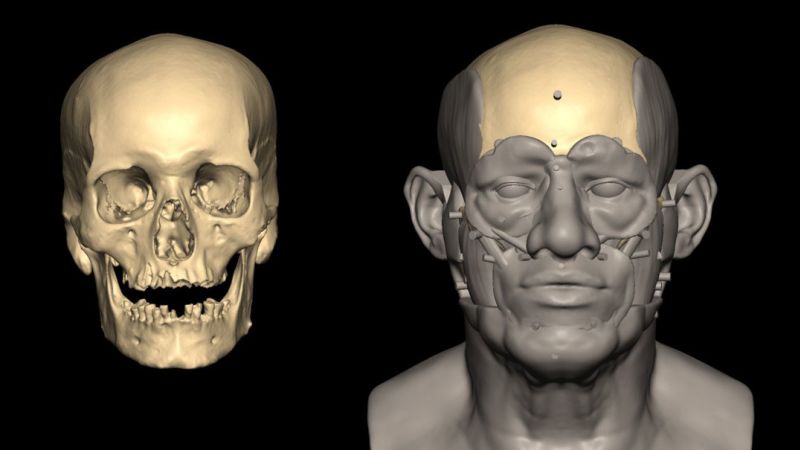

Dental anthropologist and study coauthor Joel Irish also took forensic measurements of the man’s teeth and cranium, which matched best with a Western Asian individual. Irish is a professor in the School of Biological and Environmental Sciences at Liverpool John Moores University.

The study provides a glimpse into a crucial time and place for which there haven’t been samples before, according to Iosif Lazaridis, a research associate in the department of human evolutionary biology at Harvard University. Lazaridis was not involved with the new study but has done research onancient DNA samples from Mesopotamiaand the Levant, the eastern Mediterranean area that includes modern-day Syria, Lebanon, Israel, the Palestinian territories, Jordan and parts of Turkey.

Researchers have long questioned whether the Egyptians from the beginnings of the Dynastic civilization were indigenous North Africans or Levantine, Lazaridis said.

“What this sample does tell us is that at such an early date there were people in Egypt that were mostly North African in ancestry, but with some contribution of ancestry from Mesopotamia,” Lazaridis said. “This makes perfect sense geographically.”

Lazaridis said he hopes it’s the beginning of more research on Egypt, acknowledging that while mummification helped preserve soft tissue in mummies, the chemical treatments used in the mummification process were not ideal for ancient DNA preservation.

“I think it is now shown that it is feasible to extract DNA from people from the beginnings of Egyptian civilization and the genetic history of Egypt can now begin to be written,” he said.

By studying the man’s skeleton, the team was able to determine that he was just over 5 feet tall and between 44 and 64 years old, likely closer to the end of that range — “which is incredibly old for that time period, probably like 80s would be today,” Irish said.

Genetic analysis suggests he had brown eyes and hair and dark skin. And his bones told another tale: just how hard he labored in life, which seems at odds with the ceremonial way he was buried within theceramic vessel.

Indications of arthritis and osteoporosis were evident in his bones, while features within the back of his skull and vertebra showed he was looking down and leaning forward for much of his lifetime, Irish said. Muscle markings show he was holding his arms out in front of him for extended periods of time and carrying heavy materials. The sit bones of his pelvis were also incredibly inflated, which occurs when someone sits on a hard surface over decades. There were also signs of substantial arthritis within his right foot.

Irish looked over ancient Egyptian imagery of different occupations, including pottery making, masonry, soldering, farming and weaving, to figure out how the man might have spent his time.

“Though circumstantial these clues point towards pottery, including use of a pottery wheel, which arrived in Egypt around the same time,” Irish said. “That said, his higher-class burial is not expected for a potter, who would not normally receive such treatment. Perhaps he was exceptionally skilled or successful to advance his social status.”

Before the pottery wheel and writing systems were shared between cultures, domesticated plants and animals spread across the Fertile Crescent and Egypt in the sixth millennium BC, as societies transitioned from being hunter-gatherers to living in permanent settlements. Now, the study team wonders whether human migrations were also part of that shift. Additional ancient genomes from Egypt, Africa and the Fertile Crescent could supply answers about who lived where and when.

“This is just one piece of the puzzle that is human genetic variation: each person who ever lived — and their genome — represents a unique piece in that puzzle,” Girdland-Flink said in an email. “While we will never be able to sequence everyone’s genome, my hope is that we can gather enough diverse samples from around the world to accurately reconstruct the key events in human history that have shaped who we are today.”