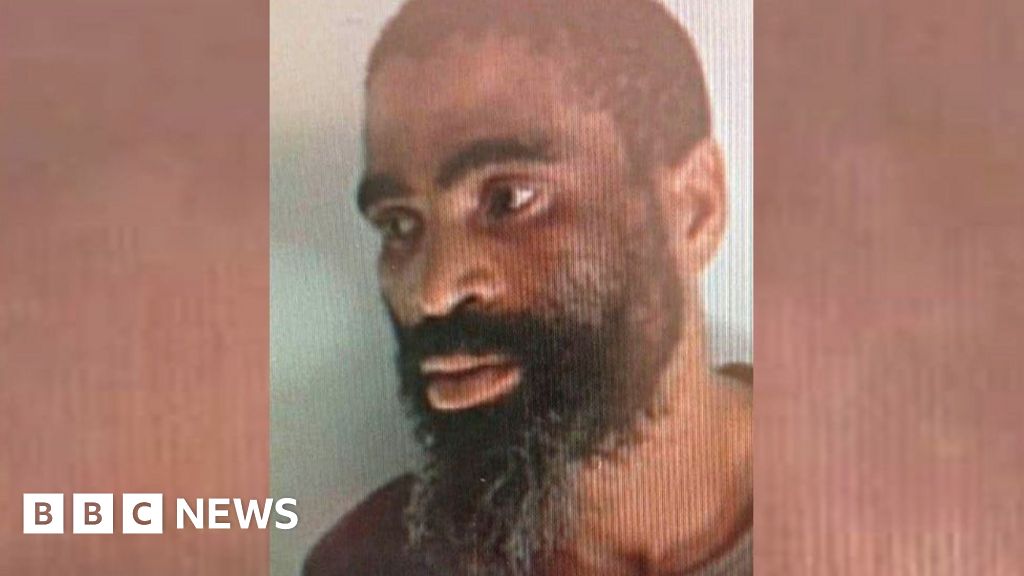

Nobody in South Africa seems to know where Tiger is. The 42-year-old from neighbouring Lesotho, whose real name is James Neo Tshoaeli, has evaded a police manhunt for the past four months. Detained after being accused of controlling the illegal operations at an abandoned gold mine near Stilfontein in South Africa, where 78 corpses were discovered underground in January, Tiger escaped custody, police allege. Four policemen, alleged to have aided his breakout, are out on bail and awaiting trial, but the authorities appear no closer to learning the fugitive's whereabouts. We went to Lesotho to find out more about this elusive man and to hear from those affected by the subterranean deaths. Tiger's home is near the city of Mokhotlong, a five-hour drive from the capital, Maseru, on the road that skirts the nation's mountains. We visit his elderly mother, Mampho Tshoaeli, and his younger brother, Thabiso. Unlike Tiger, Thabiso decided to stay at home and rear sheep for a living, rather than join the illegal miners, known as zama zamas, in South Africa. Neither of them has seen Tiger in eight years. "He was a friendly child to everyone," Ms Tshoaeli recalls. "He was peaceful even at school, his teachers never complained about him. So generally, he was a good person," she says. Thabiso, five years younger than Tiger, says they both used to look after the family sheep when they were children. "When we were growing up he wanted to be a policeman. That was his dream. But that never happened because, when our father passed away, he had to become the head of the family." Tiger, who was 21 at the time, decided to follow in his father's footsteps and headed to South Africa to work in a mine - but not in the formal sector. "It was really hard for me," says his mother. "I really felt worried for him because he was still fragile and young at that time. Also because I was told that to go down into the mine, they used a makeshift lift." He would come back when he got time off or for Christmas. And during that first stint as a zama zama his mother said he was the family's main provider. "He really supported us a lot. He was supporting me, giving me everything, even his siblings. He made sure that they had clothes and food." The last time his family saw or heard from him was in 2017 when he left Lesotho with his then wife. Shortly after, the couple separated. "I thought maybe he'd remarried, and his second wife wasn't allowing him to come back home," she says sadly. "I've been asking: 'Where is my son?' "The first time I heard he was a zama zama at Stilfontein, I was told by my son. He came to my house holding his phone and he showed me the news on social media and explained that they were saying he escaped from the police." The police say several illegal miners described him as one of the Stilfontein ring leaders. His mother does not believe he could have been in this position and says seeing the coverage of him has been upsetting. "It really hurts me a lot because I think maybe he will die there, or maybe he has died already, or if he's lucky to come back home, maybe I won't be here. I'll be among the dead." A friend of Tiger's from Stilfontein, who only wants to be identified as Ayanda, tells me they used to share food and cigarettes before supplies dwindled. He also casts doubt on the "ringleader" label, saying that Tiger was more middle management. "He was a boss underground, but he's not a top boss. He was like a supervisor, someone who could manage the situation where we were working." Mining researcher Makhotla Sefuli thinks it was unlikely that Tiger was at the top of the illegal mining syndicate in Stilfontein. He says those in charge never work underground. "The illegal mining trade is like a pyramid with many tiers. We always pay attention to the bottom tier, which is the workers. They are the ones who are underground. "But there is a second layer… they supply cash to the illegal miners. "Then you've got the buyers… they buy [the gold] from those who are supplying cash to the illegal miners." At the top are "some very powerful" people, with "close proximity to top politicians". These people make the most money, but do not get their hands dirty in the mines. Supang Khoaisanyane was one of those at the bottom of the pyramid and he paid with his life. The 39-year-old's body was among those discovered in the disused gold mine in January. He, like many of the others who perished, had migrated to South Africa. Walking into his village, Bobete, in the Thaba-Tseka district, feels like stepping back in time. The journey there is full of obstacles. After crossing a rickety bridge barely wide enough to hold our car, we are faced with a long drive up unpaved mountain roads with no safety barriers. More than once it feels likely we will not make it to the top. But when we do, the scenery is pristine. Seemingly untouched by modernity. Dozens of small, thatched huts, their walls made from mountain stone, dot the rolling green hills. Right next door to the late Supang's family home is the unfinished house he was building for his wife and three children. Unlike most of the dwellings in the village, the house is made of cement, but it is missing a roof, windows and doors. The empty spaces are an unintentional memorial to a man who wanted to help his family. "He left the village because he was struggling," his aunt Mabolokang Khoaisanyane tells me. Next to her Supang's wife and one of his children lay down on a mattress on the floor, staring sadly into space. "He was trying to find money in Stilfontein, to feed his family, and to put some roofing on his house," Ms Khoaisanyane says. The house was built with money raised from a previous work trip to South Africa by Supang - a trip that many of those from Lesotho have made over the decades drawn by the opportunities of the much richer neighbour. His aunt adds that before he left the second time, three years ago, his job prospects at home were non-existent. "It's very terrible here, that's why he left. Because here all you can do is work on short government projects. But you work for a short time and then that's it." This landlocked country - entirely surrounded by South Africa - is one of the poorest in the world. Unemployment stands at 30% but for young people the rate is almost 50%, according to official figures. Supang's family say they did not realise he was working as a zama zama until a relative called them to say he had died underground. They thought he had been working in construction and had not heard from him since he left Bobete in 2022. Ms Khoaisanyane says that during the phone call, they were told that what caused the deaths of most of those underground in Stilfontein was a lack of food and water. Many of the more than 240 who were rescued came out very ill. Stilfontein made global headlines late last year when the police implemented a controversial new strategy to crack down on illegal mining. They restricted the flow of food and water into the mine in an attempt to "smoke out" the workers, as one South African minister put it. In January, a court order forced the government to launch a rescue operation. Supang's family say they understand what he was doing was illegal but they disagree with how the authorities dealt with the situation. "They tortured these people with hunger, not allowing food and medication to be sent down. It makes us really sad that he was down there without food for that long. We believe this is what ended his life," his aunt says. The dead miner's family have finally received his body and buried him near his half-finished home. But Tiger's mother and brother are still waiting for news about him. The South African police say the search continues, though it is not clear if they have got any closer to finding him. Go toBBCAfrica.comfor more news from the African continent. Follow us on Twitter@BBCAfrica, on Facebook atBBC Africaor on Instagram atbbcafrica

South Africa's hunt for 'Tiger' - alleged illegal mining kingpin

TruthLens AI Suggested Headline:

"Authorities Continue Search for Alleged Illegal Mining Kingpin 'Tiger' in South Africa"

TruthLens AI Summary

James Neo Tshoaeli, known as 'Tiger,' has been evading authorities in South Africa for the past four months after escaping custody following accusations of controlling illegal mining operations in Stilfontein. This area gained notoriety when 78 corpses were discovered in an abandoned gold mine in January, raising concerns over the dangerous conditions faced by illegal miners, known as zama zamas. Tiger's family, residing in Lesotho, has not seen him in years, with his mother expressing deep concern for his well-being and lamenting the negative portrayal of her son in the media. She recalls Tiger as a peaceful child with aspirations to become a policeman, but circumstances forced him to leave home at a young age to support his family through illegal mining activities. Despite reports labeling him as a 'ringleader' in the illegal operations, acquaintances describe him as a middle management figure rather than a top boss within the syndicate, indicating a more complex hierarchy in the illegal mining trade that often involves powerful individuals who remain detached from the dangers faced by workers underground.

The tragic fate of many illegal miners, including that of Supang Khoaisanyane, who died in the same mine, highlights the grim realities of life for those seeking better opportunities in South Africa. Families of the deceased miners express their grief and frustration, particularly regarding the South African government's controversial tactics to combat illegal mining, which included restricting access to food and water for those trapped underground. This approach has been criticized as inhumane and has contributed to the deaths of many miners. The Khoaisanyane family, who thought Supang was working in construction, only learned of his tragic end when they were informed of his death underground. Meanwhile, Tiger's mother continues to await news of her son, as police efforts to locate him remain ongoing but have yielded little success, leaving families in despair over the uncertainty of their loved ones' fates in the perilous world of illegal mining.

TruthLens AI Analysis

The article highlights the ongoing manhunt for James Neo Tshoaeli, also known as "Tiger," an alleged kingpin of illegal mining operations in South Africa. This story is timely and significant as it sheds light on the underground economy and the social implications of illegal mining in the region, particularly in light of the tragic discovery of numerous corpses at a mine associated with these activities.

Public Sentiment and Perception

The narrative seeks to evoke a sense of intrigue and concern among the South African public regarding the prevalence of illegal mining operations and the associated dangers. By focusing on Tiger's background and his family's perspective, the article humanizes the issue, potentially generating sympathy for both the victims of illegal mining and the families of those involved. The portrayal of Tiger as a once-promising individual who was forced into a life of crime due to socio-economic pressures may elicit mixed feelings, including empathy and frustration towards the larger systemic issues at play.

Potential Concealments

While the article emphasizes the manhunt and the immediate circumstances surrounding Tiger's escape, it may obscure broader discussions about the role of corruption within law enforcement and the socio-economic conditions driving individuals to engage in illegal mining. By focusing on the individual narrative, there might be an implicit intention to divert attention from institutional failures and the need for more comprehensive policy responses to illegal mining.

Credibility Assessment

This news piece appears to be grounded in factual reporting, with specific references to events such as the discovery of corpses and the alleged police involvement in Tiger's escape. However, sensational elements may be present in the framing of Tiger’s character and the dramatic details of the manhunt. The credibility of the story largely depends on the accuracy of the claims regarding the police's actions and the portrayal of the illegal mining situation in South Africa.

Social and Economic Implications

The implications of this story are multifaceted. It could lead to increased public discourse surrounding illegal mining, possibly prompting calls for reform in mining regulations and law enforcement practices. The article may also resonate with communities affected by illegal mining, potentially mobilizing grassroots activism for safer working conditions and better economic opportunities.

Target Audience

The article seems to appeal to a broad audience, particularly those interested in social justice, crime, and economic disparity. It may resonate more with communities directly affected by illegal mining and those advocating for reform in mining practices and law enforcement accountability.

Impact on Markets

While the article primarily focuses on social issues, the implications for the mining sector could be significant. Increased scrutiny on illegal mining operations may lead to fluctuations in the stock prices of companies involved in legitimate mining activities, particularly if regulatory changes are anticipated as a result of heightened public awareness.

Global Context

In the context of global power dynamics, this story underscores the challenges faced by nations like South Africa, where illegal mining poses risks to both economic stability and public safety. The situation connects to broader themes of governance, economic inequality, and the search for sustainable livelihoods in developing regions.

Use of AI in Reporting

There is no direct indication that AI was used in the composition of this article, but it is possible that data-driven insights were utilized to highlight trends in illegal mining. If AI were involved, it might have influenced the framing of the narrative or the selection of data points that emphasize the urgency of the situation.

The article appears to be a mix of factual reporting and narrative-driven storytelling, aiming to draw attention to the social issues surrounding illegal mining in South Africa. While it provides valuable insights, it is essential to consider the broader context and potential biases in how the story is presented.