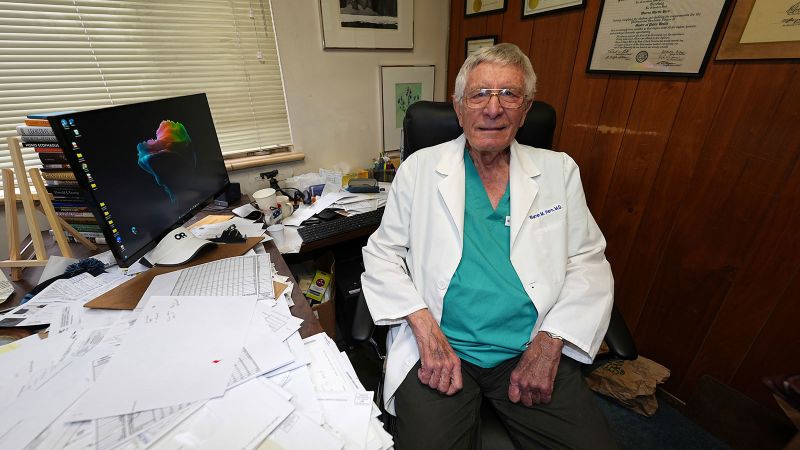

To fellow travelers, Hannah Brehm likely looked like she was taking a belated babymoon well into her third trimester. But she and her husband had received a crushing diagnosis: Their baby’s brain was not developing properly, upending their wanted pregnancy. Medical experts warned moving forward would likely mean her son would know only pain and suffering. The Minnesota couple wasn’t going to take that chance. Instead, they went to Colorado, where for decades the Boulder Abortion Clinic served as a resource for women who looked to terminate their pregnancies in the second or third trimester because of medical reasons, like Brehm, or other circumstances. After more than 50 years, that clinic quietly closed last month, leaving the U.S. with just a handful that offer abortions after 28 weeks into pregnancy — many on a case-by-case basis. The 87-year-old clinic founder, Dr. Warren Hern, says he is deeply upset: “It became impossible to continue, but closing is one of the most painful decisions of my life.” Anti-abortion advocates have celebrated the closure, calling it a step forward in protecting mothers and unborn children. While the overwhelming majority of abortions take place in the first trimester, former patients and reproductive rights advocates worry about the impact of losing an already narrow resource. “Chances are it’s not gonna happen to you. And I hope it doesn’t happen to someone else that you love, but it is happening,” Brehm said, reflecting on her experience in 2022. Reasons for late abortions Federal data shows just 1% of abortions come after 21 weeks of pregnancy, but experts believe that number is higher because some states, including California, don’t give the feds their abortion statistics. The reasons for late abortions vary. Some diagnoses like anatomy abnormalities or genetic disorders can’t happen until after 20 weeks or later into pregnancy. Other women may not find out they’re pregnant until after the first trimester. Millions of women live in a state with a strict abortion ban. Sarah Watkins traveled from Georgia to the Boulder clinic in 2019 just before 25 weeks into her pregnancy after learning her baby had a condition called trisomy 18, an extra chromosome that made it likely the baby would die in utero or shortly after birth. A genetic blood screening at 10 weeks previously dismissed chances of the condition, but a detailed ultrasound in the second trimester proved otherwise. “You can do everything right, by the book, but you still can’t find out certain things until that ultrasound at 20 weeks and sometimes even later,” she said. “And as a mom, I did not want her to feel a single moment of hurt or suffering or pain or discomfort. That’s why I made the decision.” Watkins described the medical care she received at the Hern’s clinic attentive and caring. Nevertheless, she said traveling to a place with multiple layers of bulletproof glass and a throng of protesters was a traumatic experience. Hern’s reach through the decades For years, Hern was the only provider in the U.S. to offer later abortions, starting in 1973 and developing specialized techniques and even innovating certain tools to ensure better health outcomes. But offering abortions late in pregnancy came with risks. He and his medical team received constant death threats. Someone shot through the windows of the clinic five times in 1988. Five of Hern’s colleagues who offered similar services were assassinated throughout his career, including the 2009 slaying of Dr. George Tiller in Kansas. When Hern announced the clinic’s closure in late April, the anti-abortion group Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America declared the news as a “VICTORY” in a social media post. Hern said the work was always worth it. He recalled one of his first patients who couldn’t believe the cleanliness of his operating room; she previously had an illegal abortion that left her humiliated and frightened. “She looked up at me and said ‘Please, don’t ever stop doing this,’” Hern said. “So I didn’t. Until now.” In the end, financial issues made it almost impossible to operate the clinic. Hern said patients increasingly were having trouble paying for the procedure, which hovers around $10,000 and is often not covered by insurance. Longtime personal donors were also dwindling. Hern worked with physicians over the decades, hopeful that one day they would take over his clinic, but that never worked out. “I had to make a decision really, you know, sort of on the basis of the situation at the moment that we couldn’t continue,” he said. “It was very, very painful. I see this as my personal failure.” Providers and patients wonder what’s next According to the Later Abortion Initiative by Ibis Reproductive Health, fewer than 20 clinics provide abortions after 24 weeks into pregnancy in the U.S. — though that number isn’t considered comprehensive and excludes hospitals and a handful of other clinics for security reasons. Currently, the group lists three clinics — in New Mexico, Maryland and Washington, D.C. — that provide services after 28 weeks. Five others — in Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Oregon and Washington state — will consider patients depending on physician recommendations or fetal and maternal conditions. “I think Dr. Hern has been the torchbearer for abortion leaders in pregnancy,” said Jane Armstrong, a licensed therapist in Texas who now helps support families who have terminated pregnancies for medical reasons. She ended her own pregnancy around 21 weeks in 2021. “Who will pick up the mantle? We really do need a new torchbearer right now.” A dozen states have bans on abortion at all stages of pregnancy and four more have bans that kick in after about six weeks. Abortion fund organizations, which help people arrange and pay abortions, say the bans mean a higher demand for later abortions. When people travel, it often takes more time to make appointments, gather the money needed and to catch a flight or take a drive hundreds of miles away. “Every time a clinic closes, it does impact everybody and what kinds of care they give,” said Anna Rupani, executive director of Fund Texas Choice. Shortly after the nation’s highest court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022, an all-trimester abortion clinic opened in Maryland — a partnership between certified nurse-midwife Morgan Nuzzo and Dr. Diane Horvath, an OB-GYN who specializes in complex family planning. They said they’re worried about many things when it comes to reproductive rights, including the Trump administration’s move to curtail prosecutions against people accused of blocking access to abortion clinics and reproductive health centers. But they’re also buoyed by the consistent overwhelming number of applications from providers whenever they post a position, and said that the number of clinics that offer later abortions has gone up since Roe was overturned. “This type of care is still available,” Horvath said. “It’s more rare than it was a couple weeks ago, but we want to say loud and proud that our doors are still open and there are other places still open.”

Late abortions are rare. The US just lost a clinic that offered the procedure for over 50 years

TruthLens AI Suggested Headline:

"Closure of Boulder Abortion Clinic Reduces Access to Late-Term Abortions in the U.S."

TruthLens AI Summary

Hannah Brehm and her husband faced a heartbreaking decision after receiving a diagnosis indicating severe developmental issues with their unborn child. Rather than proceeding with a pregnancy that medical experts warned would lead to immense suffering, they traveled to Colorado to seek a late-term abortion at the Boulder Abortion Clinic. This clinic, which had been a crucial resource for women needing late-term abortions for medical reasons or other circumstances, recently closed its doors after over 50 years of operation. The closure leaves the United States with only a handful of clinics that provide such services, and those are often limited to specific cases. Dr. Warren Hern, the clinic's founder, expressed deep sorrow over the decision to shut down, highlighting the emotional toll it has taken on him and the patients who relied on the clinic's care. Anti-abortion advocates have welcomed the closure as a victory, while supporters of reproductive rights express concerns about the implications for women facing similar medical crises.

The reasons for seeking late-term abortions are diverse and often complex. Many women do not discover severe fetal abnormalities until after the 20-week mark, and some may not even realize they are pregnant until later. The Boulder clinic served patients like Sarah Watkins, who traveled from Georgia to terminate her pregnancy after learning of a serious genetic condition that would cause her baby to suffer. Dr. Hern had long been a pioneer in providing later abortions, but financial difficulties ultimately led to the clinic's closure. With fewer than 20 clinics in the U.S. currently providing abortions after 24 weeks, advocates are concerned about the future of care for women with complicated pregnancies. As the landscape of reproductive health continues to change, the need for accessible late-term abortion services remains critical, prompting discussions about who will carry on the legacy of care that Dr. Hern established. The closure of the Boulder clinic underscores the ongoing challenges faced by women in states with strict abortion regulations, emphasizing the importance of maintaining access to necessary medical services for those in need.

TruthLens AI Analysis

The article examines the recent closure of the Boulder Abortion Clinic, which had provided late abortion services for over 50 years. This event is significant in the context of reproductive rights in the U.S., especially for women facing serious medical issues during pregnancy. The narrative follows the personal story of Hannah Brehm, whose family faced a tragic diagnosis, highlighting the emotional and ethical complexities surrounding late-term abortions.

Implications of the Closure

The closure of the Boulder Abortion Clinic leaves few options for women seeking late-term abortions, particularly those with medical complications or other serious circumstances. Advocates for reproductive rights express concern that this will further limit access to necessary medical care, which could disproportionately affect marginalized communities. The article aims to raise awareness about the challenges faced by women needing late abortions and the dwindling resources available to them.

Public Perception and Advocacy

By presenting personal stories alongside statistical data, the article seeks to foster empathy and understanding among readers, particularly those who may not have experienced similar situations. It contrasts the perspectives of anti-abortion advocates who celebrate the clinic's closure with the voices of women who have benefited from its services. This dual approach aims to highlight the stark realities of reproductive health decisions.

Hidden Narratives

While the article focuses on the emotional journey of women like Brehm, it may also be seen as an attempt to underscore the broader implications of limiting access to reproductive health services. The closure can be perceived as part of a larger trend toward restricting abortion rights in the U.S., which may not be as prominently discussed in more general reports on reproductive health.

Comparative Context

When compared to other reports on abortion rights, this article provides a more personal and emotional angle, which is often less emphasized in broader news coverage. It connects with ongoing debates about women's autonomy over their bodies and the legal landscape surrounding abortion, reflecting a critical moment in the ongoing discourse.

Societal Impact

The closure could lead to significant changes in public opinion regarding reproductive rights, potentially mobilizing advocacy groups to push back against restrictive laws. Economically, it may affect clinics that provide similar services, as fewer options can lead to increased demand at remaining facilities. Politically, this situation could energize both pro-choice and pro-life movements, influencing future elections and legislative actions.

Target Audience

The article likely resonates more with communities that support reproductive rights and those concerned about health care access. It aims to engage readers who may not be directly affected by late-term abortions but can empathize with the emotional weight of such decisions.

Market Reactions

From a market perspective, the closure of the clinic might not have immediate direct effects on stock prices; however, it could influence companies involved in women's health services or pharmaceuticals related to reproductive health. Advocacy groups may also see fluctuations in funding and support based on public reaction to such closures.

Global Perspective

In the context of global reproductive rights, this news piece underscores the ongoing struggles many women face regarding autonomy and health care access. It connects with broader discussions on women's rights and health in various countries, highlighting disparities in access to necessary medical procedures.

Use of Technology in Reporting

The article may have utilized AI tools for data analysis or to enhance narrative structure, but there is no definitive evidence of AI influence on the emotional tone or framing. The language used is human-centered, focusing on personal stories rather than algorithmically generated content.

Manipulative Aspects

While the piece does not overtly manipulate, it does present a specific narrative that could be interpreted as biased towards pro-choice views. The emotional storytelling may sway readers' opinions, particularly by emphasizing the personal experiences of women impacted by these laws.

In conclusion, the article provides a poignant exploration of the implications of the Boulder Abortion Clinic's closure, shedding light on the complex issues surrounding reproductive rights. Its emotional appeal and personal narratives serve to raise awareness and provoke thought among readers about the future of reproductive health care in the U.S.