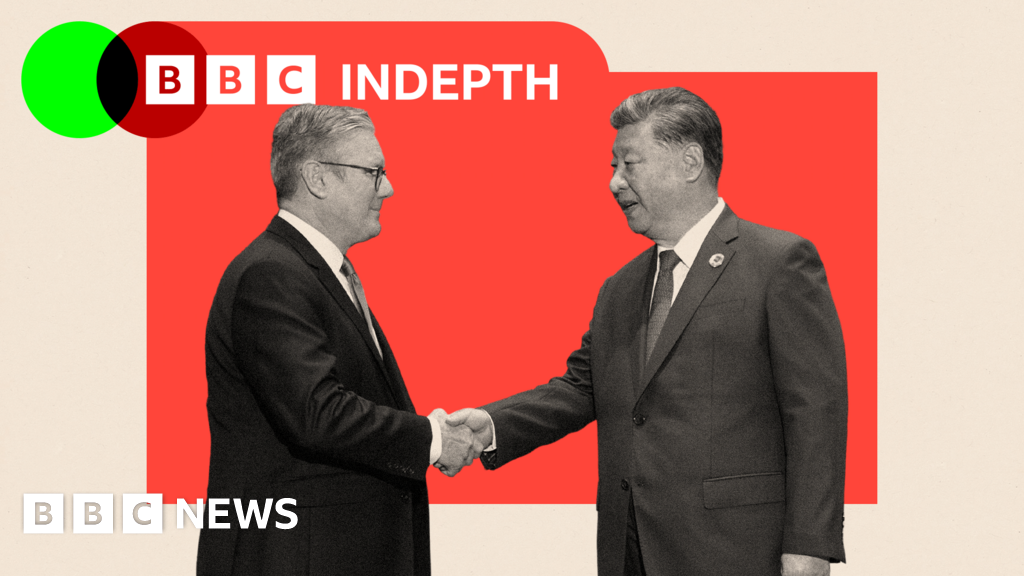

The sprawling city of Chongqing in southwestern China is an incredible sight. Built on mountainous terrain and crisscrossed by rivers, it is connected by vast elevated roads. Trains even run through some buildings. TikTokers have begun documenting their commutes in the striking urban architecture, generating millions of likes and much hype. But it is also where, on a somewhat quieter trip, mayors and their deputies from the UK recently visited - the largest British civic delegation to visit the country in modern history. The whole trip, which took place in March, received substantial Chinese media coverage, despite flying more under the radar in the UK. The impression it left on some of the politicians who travelled there was vast. "[The city is] what happens if you take the planning department and just say 'yes' to everything," reflects Howard Dawber, deputy London mayor for business. "It's just amazing." The group travelled to southern Chinese cities, spoke to Chinese mayors and met Chinese tech giants. So impressed was one deputy mayor that, on returning home, they bought a mobile phone from Chinese brand Honor (a stark contrast from the days the UK banned Huawei technology from its 5G networks, just a few years ago). Roughly half-a-dozen deals were signed on the back of the trip. The West Midlands, for example, agreed to establish a new UK headquarters in Birmingham for Chinese energy company EcoFlow. But the visit was as much about diplomacy as it was trade, says East Midlands deputy mayor Nadine Peatfield, who attended. "There was a real hunger and appetite to rekindle those relationships." To some, it was reminiscent of the "golden era" of UK-China relations, a time when then-Prime Minister David Cameron and Chinese President Xi Jinping shared a basket of fish and chips and a pint. Those days have long felt far away. Political ties with China deteriorated under former UK Conservative Prime Ministers Boris Johnson, Rishi Sunak and Liz Truss. The last UK prime minister to visit China was Theresa May, in 2018. But the recent delegation - and the talk of Sir Keir Starmer possibly visiting China later this year - suggests a turning point in relations. But to what greater intent? The course correction seemed to begin with the closed-door meeting between Sir Keir and Chinese President Xi in Brazil last November. The prime minister signalled that Britain would look to cooperate with China on climate change and business. Since then, Labour's cautious pursuit of China has primarily focused on the potential financial upsides. In January, Chancellor Rachel Reeves co-chaired the first UK-China economic summit since 2019, in Beijing. Defending her trip, she said: "Choosing not to engage with China is no choice at all." Reeves claimed re-engagement with China could boost the UK economy by £1bn, with agreements worth £600m to the UK over the next five years — partially achieved through lifting barriers that restrict exports to China. Soon after, Energy Secretary Ed Miliband resumed formal climate talks with China. Miliband said it would be "negligence" to future generations not to have dialogue with the country, given it is the world's biggest carbon emitter. Labour simply describes its approach as "grown-up". But it all appears to be a marked shift from the last decade of UK-China relations. During the so-called "golden era", from 2010, the UK's policy towards China was dominated by the Treasury, focusing on economic opportunities and appearing to cast almost all other issues, including human rights or security, aside. By September 2023, however, Rishi Sunak said he was "acutely aware of the particular threat to our open and democratic way of life" posed by China. Labour claimed in its manifesto that it would bring a "long-term and strategic approach". China has a near monopoly on extracting and refining rare earth minerals, which are critical to manufacturing many high-tech and green products. For example, car batteries are often reliant on lithium, while indium is a rare metal used for touch screens. This makes China a vital link in global supply chains. "China's influence is likely to continue to grow substantially globally, especially with the US starting to turn inwards," says Dr William Matthews, a China specialist at Chatham House think tank. "The world will become more Chinese, and whilst that is difficult for any Western government, there needs to be sensible engagement from the get-go." Andrew Cainey, a director of the UK National Committee on China, an educational non-profit organisation, says: "China has changed a lot since the Covid-19 pandemic. To have elected officials not having seen it, it's a no brainer for them to get back on the ground". Certainly many in the UK's China-watching community believe that contact is an essential condition to gain a clearer-eyed view of the opportunities posed by China, but also the challenges. The opportunities, some experts say, are largely economic, climate and education-related. Or as Kerry Brown, Professor of Chinese Studies at King's College London, puts it: "China is producing information, analysis and ways of doing things that we can learn from". He points to the intellectual, technological, AI, and life sciences opportunities. Not engaging with China would be to ignore the realities of geopolitics in the 21st century, in Dr Matthew's view, given that it is the world's second largest economy. However he also believes that engagement comes with certain risks. But Charles Parton, who spent 22 years of his diplomatic career working in or on China, raises questions about the UK's economic andnational security. For example, the government is reportedly weighing up proposals for a Chinese company to supply wind turbines for an offshore windfarm in the North Sea. Mr Parton warns against allowing China access to the national grid: "It wouldn't be difficult in a time of high tension to say, 'by the way, we can turn off all your wind farms'". But earlier this year, the China Chamber of Commerce to the EU issued a statement expressing concern over the "politicisation" of deals between wind developers in Europe and Chinese turbine suppliers. James Sullivan, director of Cyber and Tech at defence think tank Rusi, notes there are also some questions around cyberspace. "China's activities in cyberspace appear to be more strategically and politically focused compared to previous opportunistic activities," he says. As for defence, the UK's recently published defence review describes China as a "sophisticated and persistent challenge", with Chinese technology and its proliferation to other countries "already a leading challenge for the UK". Ken McCallum, MI5 director general, meanwhile, has previously warned of asustained campaign on an "epic scale"of Chinese espionage abroad. But Prof Brown pushes back on some concerns about espionage, saying some media narratives about this are a "fairytale". Beijing has always dismissed accusations of espionage as attempts to "smear" China. Sir Keir and his team will no doubt be closely monitoring how this is all viewed by Washington DC. Last month, President Donald Trump's trade advisor Peter Navarro described Britain as "an all too compliant servant of Communist China", urging the UK against deepening economic ties. "When it comes to foreign policy towards China, America's influence on policy will be quite substantive compared with say continental Europe," says Dr Yu Jie of China Foresight at LSE IDEAS think tank. Most analysts I speak to in both the UK and China are still clear on the need for the two countries to get back in the same room, even if they differ on where to draw the line: in which areas should Westminster cooperate and where should it stay clear. These red lines have not yet been drawn, and experts say that without some kind of playbook, it is difficult for businesses and elected officials to know how to engage. "You can only keep firefighting specific issues for so long without developing a systematic plan," warns Mr Cainey. Certain thorny issues have arisen, including Chinese investments in the UK. For example in April when the government seized control of British Steel from its former Chinese owner Jingye, to prevent it from being closed down, Business Secretary Jonathan Reynolds admitted that he would "look at a Chinese firm in a different way" when considering investment in the UK steel industry. China's foreign ministry spokesperson, Lin Jian, warned that Labour should avoid "linking it to security issues, so as not to impact the confidence of Chinese enterprises in going to the UK". After Starmer met Xi last year, he said the government's approach would be "rooted in the national interests of the UK", but acknowledged areas of disagreement with China, including on human rights, Taiwan and Russia's war in Ukraine. Securing the release of pro-democracy activist and British citizen Jimmy Lai from a Hong Kong prison is, he has said, a "priority" for the government. Labour's manifesto broadly pledged: "We will cooperate where we can, compete where we need to, and challenge where we must." What is still lacking, however, is the fine print. Asked about the British government's longer-term strategy, Mr Parton replied: "No.10 doesn't have a strategy." He tells me he has some specific advice: "Go with your eyes open," he says. "But have a clear idea of what needs protecting, and a willingness to take some short-term financial hits to protect long-term national security." Labour has suggested that some clarity on their approach will be provided through the delayed China "audit", a cross-government exercise launched last year, which will review the UK's relations with China. The audit is due to be published this month, but many doubt that it will resolve matters. "If we see a visit from Starmer to Beijing, that will be an indication that the two sides have actually agreed with something, and that they would like to change and improve their bilateral relationship," says Dr Yu. But many people in Westminster remain China-sceptic. And even if the audit helps Britain better define what it wants out of its relationship with China, the question remains, do MPs and businesses have the China-related expertise to get the best out of it? According to Ruby Osman, China analyst at the Tony Blair Institute, there is an urgent need to build the UK's China capabilities in a more holistic way, focusing on diversifying the UK's points of contact with China. "If we want to be in a position where we are not just listening to what Beijing and Washington want, there needs to be investment in the talent pipeline coming into government, but also think tanks and businesses who work with China," she argues. And if that's the case, then irrespective of whether closer ties with China is viewed as a security threat, an economic opportunity, or something in between, the UK might be in a better position to engage with the country. Top image credit: PA BBC InDepthis the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

Labour is cosying up to China after years of rollercoaster relations

TruthLens AI Suggested Headline:

"UK Labour Party Seeks to Revive Relations with China Amidst Historical Tensions"

TruthLens AI Summary

In March, a significant delegation of British mayors and their deputies made a historic visit to Chongqing, China, marking the largest civic delegation from the UK to the country in modern times. The trip received considerable attention in Chinese media, showcasing the impressive urban landscape of Chongqing, characterized by its mountainous terrain and intricate network of elevated roads. The delegation engaged with local Chinese officials, explored potential trade agreements, and discussed technology partnerships with prominent Chinese firms. This visit resulted in several deals, including the establishment of a UK headquarters in Birmingham for the Chinese energy company EcoFlow, highlighting a renewed interest in fostering economic ties between the two nations. The trip was not just focused on commerce; it also underscored a diplomatic effort to mend the historically strained relations that have developed over recent years, particularly during the leadership of former UK Prime Ministers who took a more confrontational stance towards China.

The evolving approach of the UK Labour Party towards China indicates a potential shift in strategy under the leadership of Sir Keir Starmer. Following a closed-door meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping in Brazil, Labour has emphasized the importance of re-engaging with China, particularly concerning economic cooperation and climate change initiatives. Recent statements from Labour officials, including Chancellor Rachel Reeves, suggest that avoiding engagement with China is no longer seen as a viable option. With a focus on the economic benefits of collaboration, Labour's stance appears to echo the earlier 'golden era' of UK-China relations, which prioritized economic opportunities while often overlooking critical issues such as human rights. However, concerns remain regarding national security and the implications of deepening ties with China, especially in technology and infrastructure sectors. As the UK government prepares to release a comprehensive audit of its relations with China, the path forward remains uncertain, with a need for clarity on the balance between economic engagement and national security considerations.

TruthLens AI Analysis

The recent article highlights a significant shift in the UK’s approach to its relationship with China, particularly through a recent visit by British mayors to Chongqing. This visit signifies a rekindling of diplomatic ties after a period of strained relations. The article appears to serve multiple purposes, from showcasing positive interactions with China to emphasizing the potential benefits of such diplomatic engagements.

Diplomatic Reconciliation

The article emphasizes the rekindling of relationships between the UK and China, reminiscent of a "golden era" in bilateral relations. It points out the enthusiasm among UK officials to establish new partnerships, underlining the importance of diplomacy alongside trade. This narrative aims to frame the relationship positively, suggesting that cooperation could yield significant benefits for both nations.

Trade Opportunities

The mention of signed deals, such as the establishment of a UK headquarters for a Chinese energy company, highlights the practical benefits of the visit. By focusing on tangible outcomes, the article seeks to present the UK’s engagement with China as not only politically beneficial but also economically advantageous. This could appeal to business-oriented readers and stakeholders looking for growth opportunities.

Contrasting Past Policies

The article contrasts the current engagement with the previous UK government’s approach, which was marked by a more confrontational stance towards China. This juxtaposition serves to illustrate a shift in policy that may resonate well with audiences who favor more collaborative international relations. By acknowledging past tensions while highlighting current cooperation, the article attempts to normalize the relationship.

Potential Manipulation or Bias

While the article presents a largely positive view of the UK-China relationship, it may downplay ongoing concerns related to human rights and geopolitical tensions. By focusing heavily on diplomatic and economic aspects, it risks creating a one-dimensional narrative that may not fully represent the complexities of the relationship. This could be seen as a subtle form of manipulation, directing public perception towards a more favorable view.

Public Sentiment and Economic Impact

The rekindling of ties with China could influence public sentiment positively, especially among those who see economic benefits. However, it may also alienate segments of the population concerned about China’s human rights record and its geopolitical ambitions. The potential for increased trade could impact stock markets, particularly for companies involved in technology and energy sectors.

Community Support and Target Audience

The article likely appeals to business communities and political figures interested in international relations. It may resonate more with those who prioritize economic growth and diplomatic engagement over more critical perspectives on China’s policies.

Global Power Dynamics

In the context of global power dynamics, this article reflects broader trends of countries reassessing their relationships with China. As nations navigate complex geopolitical landscapes, the UK’s approach could signal a shift towards increased cooperation, which may influence China’s global standing and relationships with other countries.

AI Involvement in Article

It is plausible that AI tools were utilized in crafting this article, particularly in data analysis and trend identification. The language and structure might suggest a deliberate effort to shape public perception positively. If AI was involved, it may have prioritized certain narratives over others, emphasizing economic cooperation while downplaying potential conflicts.

Overall, the article offers a largely optimistic view of UK-China relations, focusing on the benefits of rekindled ties while potentially glossing over more contentious issues. The reliability of the information hinges on its balance and representation of different perspectives on the relationship.