Ruma was having lunch on a summer day in 2021 when her phone began blowing up with notifications. When she opened the messages, they were devastating. Photos of her face had been taken from social media and edited onto naked bodies, shared with dozens of users in a chat room on the messaging app Telegram. The comments in screen shots of the chat room were demeaning and vulgar – as were the texts from the anonymous messenger who had sent her the images. “Isn’t it funny? … Watching your own sex video,” they wrote. “Tell me you honestly enjoy this.” The harassment escalated into threats to share the images more widely and taunts that police wouldn’t be able to find the perpetrators. The sender seemed to know her personal details, but she had no way to identify them. “I was bombarded with all these images that I had never imagined in my life,” said Ruma, who CNN is identifying with a pseudonym for her privacy and safety. While revenge porn – the nonconsensual sharing of sexual images – has been around for nearly as long as the internet, the proliferation of AI tools means that anyone can be targeted by explicit deepfakes, even if they’ve never taken or sent a nude photo. South Korea has had a particularly fraught recent history of digital sex crimes, from hidden cameras in public facilities to Telegram chat rooms where women and girls were coerced and blackmailed into posting demeaning sexual content. But deepfake technology is now posing a new threat, and the crisis is particularly acute in schools. Between January and early November last year, more than 900 students, teachers and staff in schools reported that they fell victim to deepfake sex crimes, according to data from the country’s education ministry. Those figures do not include universities, which have also seen a spate of deepfake porn attacks. In response, the ministry established an emergency task force. And in September, legislators passed an amendment that made possessing and viewing deepfake porn punishable by up to three years in prison or a fine of up to 30 million won (over $20,000). Creating and distributing non-consensual deepfake explicit images now has a maximum prison sentence of seven years, up from five. South Korea’s National Police Agency has urged its officers to “take the lead in completely eradicating deepfake sex crimes.” But of 964 deepfake-related sex crime cases reported from January to October last year, police made 23 arrests, according to a Seoul National Police statement. Legislator Kim Nam-hee told CNN that “investigations and punishments have been too passive so far.” So, some victims, like Ruma, are conducting their own investigations. Victims taking action Ruma was a 27-year-old university student when her nightmare first began. When she went to the police, they told her they would request user information from Telegram, but warned the platform was notorious for not sharing such data, she said. Once an outgoing student who enjoyed school and an active social life, Ruma said the incident had completely changed her life. “It broke my whole belief system about the world,” she said. “The fact that they could use such vulgar, rough images to humiliate and violate you to that extreme extent really damages you almost irrevocably.” She decided to act after learning that investigations into reports by other students had ended after a few months, with police citing difficulty in identifying suspects. Ruma and fellow students sought help from Won Eun-ji, an activist who gained national fame for exposing South Korea’s largest digital sex crime group on Telegram in 2020. Won agreed to help, creating a fake Telegram account and posing as a man in his 30s to infiltrate the chat room where the deepfake images had circulated. She spent nearly two years carefully gathering information and engaging other users in conversation, before coordinating with police to help carry out a sting operation. When police confronted the suspect, Won sent him a Telegram message. His phone pinged – he had been caught. Two former students from the prestigious Seoul National University (SNU) were arrested last May. The main perpetrator was ultimately sentenced to 9 years in prison for producing and distributing sexually exploitative materials, while an accomplice was sentenced to 3.5 years in prison. Police told CNN further investigations identified at least 61 victims, including 12 current and former SNU students. Seoul National University, in a briefing after the incident, said “the school will strengthen preventative education to raise awareness among the members of the university about digital sex crimes and do its best to protect victims and prevent recurrence.” Excerpts of the ruling shared by Ruma’s lawyers state, “The fake explicit materials produced by the perpetrator are repugnant, and the conversations surrounding them are shocking … They targeted victims as if they were hunting prey, sexually insulted the victims and destroyed their dignity by using photos from graduations, weddings, and family gatherings.” In response to the verdict, Ruma told CNN, “I didn’t expect the ruling to align exactly with the prosecution’s request. I’m happy, but this is only the first trial. I don’t feel entirely relieved yet.” Ruma’s case is just one of thousands across South Korea – and some victims had less help from police. Public often unsympathetic One high school teacher, Kim, told CNN she first learned she was being targeted for exploitation in July 2023, when a student urgently showed her Twitter screenshots of inappropriate photos taken of her in the classroom, focusing on her body. “My hands started to shake,” she recalled. “When could this photo have been taken, and who would upload such a thing?” CNN is identifying Kim by her last name only for her privacy and safety. But she said the situation worsened two days later. Her hair was made messy, and her body was altered to make it look like she was looking back. The manipulated picture of her face was added onto nude photos. The sophisticated technology made the images unnervingly realistic. Police told her that their only option to identify the poster was to request user information from Twitter, the social media platform bought by Elon Musk in 2022 and rebranded as X in 2023, with an emphasis on free speech and privacy. Kim and a colleague, also a victim of a secret filming, feared that using official channels to identify the user would take too long and launched their own investigation. They identified the person: a quiet, introverted student “someone you’d never imagine doing such a thing,” Kim said. The person was charged but regardless of what happens in court, she said life will never be the same. She said a lack of public empathy has frustrated her too. “I read a lot of articles and comments about deepfakes saying, ‘Why is it a serious crime when it’s not even your real body?’” Kim said. According to X’s current policy, obtaining user information involves obtaining a subpoena, court order, or other valid legal document and submitting a request on law enforcement letterhead via its website. X says it’s company policy to inform users that a request has been made. Its rules on authenticity state that users “may not share inauthentic content on X that may deceive people or lead to harm.” Pressure on social platforms to act Won, the activist, said that for a long time, sharing and viewing sexual content of women was not considered a serious offense in South Korea. Though pornography is banned, authorities have long failed to enforce the law or punish offenders, Won said. Societal apathy makes it easier for perpetrators to commit digital sex crimes, Won said, including what she called “acquaintance humiliation.” “Acquaintance humiliation” often begins with perpetrators sharing photos and personal information of women they know on Telegram, offering to create deepfake content or asking others to do so. Victims live in fear as attackers often know their personal information – where they live, work, and even details about their families – posing real threats to their safety and allowing anonymous users to harass women directly. Since South Korea’s largest digital sex exploitation case on Telegram in 2020, Won said the sexual exploitation ecosystem had fluctuated, shrinking during large-scale police investigations but expanding again once authorities ease off. The victims CNN interviewed all pushed for heavier punishment for perpetrators. While prevention is important, “there’s a need to judge these cases properly when they occur,” Kim said. Online platforms are also under pressure to act. Telegram, which has become a fertile space for various digital crimes, announced it would begin sharing user data with authorities as part of a broader crackdown on illegal activities. The move came after the company’s CEO Pavel Durov was arrested in August in France on a warrant relating to Telegram’s lack of moderation, marking a turning point for a platform long recognized for its commitment to privacy and encrypted messaging. Durov is under formal investigation but has been allowed to leave France, he said in a post on Telegram. Last September, South Korea’s media regulator said Telegram had agreed to establish a hotline to help wipe illegal content from the app, and that the company had removed 148 digital sex crime videos as requested by the regulator. Won welcomed this move, but with some skepticism – saying governments should remove the app from app stores, to prevent new users from signing up, if Telegram doesn’t show substantial progress soon. “This is something that has been delayed for far too long,” she said. In a statement to CNN, Telegram said the company “has a zero-tolerance policy for illegal pornography” and uses “a combination of human moderation, AI and machine learning tools and reports from users and trusted organizations to combat illegal pornography and other abuses of the platform.” A meaningful breakthrough occurred this January, marking the first time Korean authorities successfully obtained crime-related data from Telegram, according to Seoul police. Fourteen people were arrested, including six minors, for allegedly sexually exploiting over 200 victims through Telegram. The criminal ring’s mastermind had allegedly targeted men and women of various ages since 2020, and more than 70 others were under investigation for allegedly creating and sharing deepfake exploitation materials, Seoul police said. Meanwhile, victims told CNN they hope other women in their position can receive more support from the police and the courts going forward. “No matter how much punishments are strengthened, there are still far more victims who suffer because their perpetrators have not been caught, and that’s why it feels like the verdict is still far from being a true realization of change or justice,” Ruma said. “There’s a long way to go.”

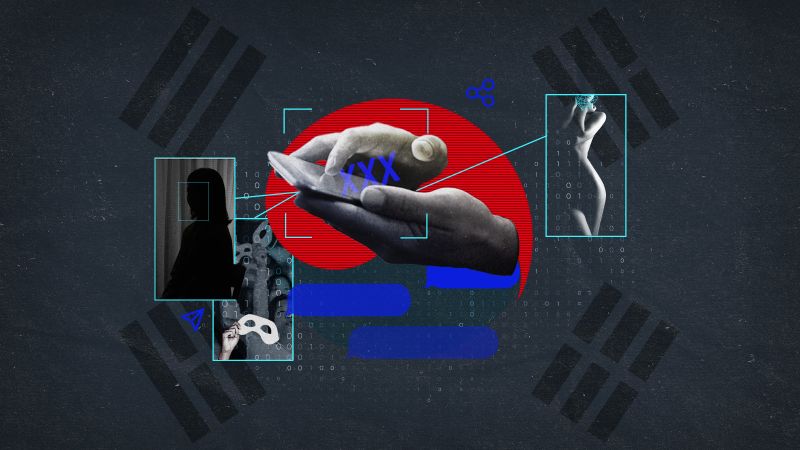

Deepfake porn is destroying real lives in South Korea

TruthLens AI Suggested Headline:

"Rising Deepfake Pornography Crisis in South Korea Highlights Victim Struggles and Legal Challenges"

TruthLens AI Summary

In South Korea, the rise of deepfake pornography has exacerbated the ongoing crisis of digital sex crimes, profoundly affecting victims like Ruma, a university student whose life was turned upside down after her face was manipulated onto explicit images and shared in a Telegram chat room. The incident, which began with notifications of these images, led to a barrage of harassment and threats from anonymous users, showcasing the alarming ease with which technology can violate personal privacy. This issue is not isolated; reports indicate that over 900 cases of deepfake sex crimes were documented in schools alone between January and November of the previous year, prompting the education ministry to form an emergency task force and legislate stricter penalties for perpetrators. Despite these measures, the response from law enforcement has been criticized as inadequate, with only a fraction of cases leading to arrests, leaving many victims feeling abandoned and compelled to seek justice on their own.

The societal response to deepfake pornography reflects a troubling lack of empathy for victims, with some public commentary suggesting that such crimes are less serious due to the non-physical nature of the images. Activist Won Eun-ji, who has worked tirelessly to expose perpetrators, highlighted the pervasive culture of impunity surrounding digital sex crimes in South Korea. Victims like Ruma and Kim, another educator who faced a similar violation, have taken matters into their own hands, conducting investigations to identify their harassers. While recent legislative efforts and police actions signal a potential shift in addressing these crimes, the path to justice remains fraught with challenges, as many victims continue to suffer in silence, fearing further harassment and the inadequacy of legal protections. The urgent need for societal change and robust legal frameworks remains a pressing issue as victims advocate for more effective support and accountability mechanisms.

TruthLens AI Analysis

The article highlights the alarming issue of deepfake pornography in South Korea, shedding light on the severe consequences it has on individuals' lives. By sharing the distressing experience of "Ruma," the article illustrates how advanced technology can be exploited to harass and intimidate people, especially women. The societal implications of such acts are profound, prompting a discussion on the need for stronger regulations and protections against digital sex crimes.

Impact of AI Technology on Privacy

The rise of deepfake technology represents a significant threat to personal privacy. Unlike traditional revenge porn, which typically relies on images taken consensually, deepfakes can be created without the victim's consent or even their knowledge. This development raises critical questions about the ethics of AI and the responsibility of tech companies in preventing misuse.

Wider Societal Issues

The article reflects South Korea's ongoing struggle with digital sex crimes, highlighting a broader cultural issue regarding misogyny and the treatment of women. The mention of past incidents involving hidden cameras and coerced sexual content in Telegram chat rooms suggests a systemic problem that extends beyond individual cases. This context implies a need for societal change and greater awareness of the challenges faced by women in digital spaces.

Legislative Response and Its Importance

The establishment of an emergency task force by the education ministry and the passing of an amendment to penalize deepfake pornography demonstrate a governmental recognition of the issue. Such measures are essential in protecting victims and deterring potential offenders. However, the effectiveness of these laws will depend on proper enforcement and public awareness.

Potential Reactions and Broader Implications

The public response to the article may lead to increased support for women's rights organizations and advocacy for stricter regulations on digital content. Economically, there could be increased investment in technologies aimed at detecting and combating deepfake content. Politically, this issue may influence future elections or legislative agendas focused on digital security and women's rights.

Target Audience and Community Support

The article seems to resonate particularly with feminist groups and advocates for digital rights, aiming to raise awareness about the exploitation of women in online spaces. By focusing on the personal stories of victims, it seeks to garner empathy and support for systemic changes.

Market Impact and Global Relevance

While this specific issue may not directly affect stock markets, companies involved in cybersecurity and digital rights may see fluctuations in interest or investment. It's important to note that the conversation around deepfakes and digital privacy is relevant to global discussions about technology, security, and human rights.

AI's Role in the Narrative

Given the nature of the news, it's possible that AI tools were utilized to analyze data or even to generate certain parts of the text. However, the emotional depth and personal anecdotes suggest human authorship in crafting a compelling narrative. The framing of the story emphasizes the urgency of addressing deepfake technology's implications on privacy and personal safety.

Manipulative Aspects of the Reporting

There is a degree of manipulation in how the article presents deepfake pornography as a pressing societal issue. By focusing on personal victimization and the emotional toll it takes, the article aims to evoke a strong reaction from readers. While this approach can effectively raise awareness, it also risks sensationalizing the issue without addressing the broader systemic factors at play.

In conclusion, the article serves as a critical reminder of the dangers posed by technology in the realm of personal privacy and safety. While it is grounded in real experiences and factual data, the framing and emotional appeals suggest an intention to drive societal change regarding digital rights and protections for individuals.