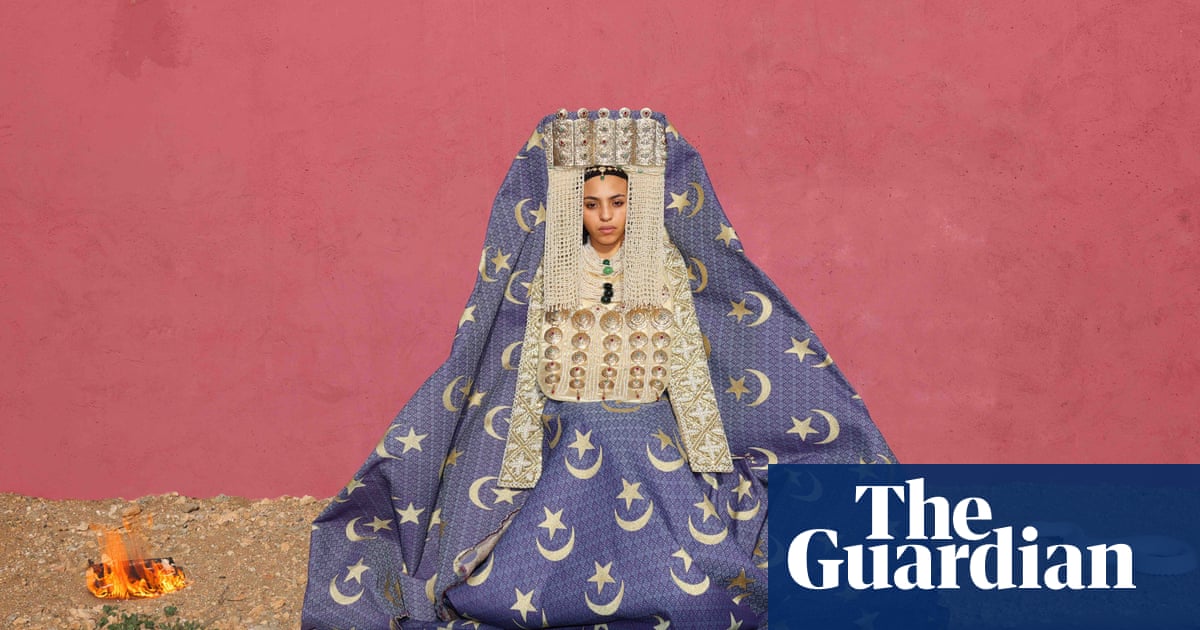

Through my series Dry Land, I explore the deep contradictions embedded in Moroccan marriage traditions – how they oscillate between sacred ritual and social imprisonment. This image was taken on the arid outskirts of Marrakech, where the earth is cracked and open, a stark contrast to the heaviness of the dress the woman carries on her body. It shines beautifully but restricts, almost theatrical in its weight.

The woman stands still in a traditional Fassi bridal garment, a piece that is both exquisite and nearly unbearable to wear. It is a dress I grew up seeing and quietly fearing – not just for its grandeur, but for what it symbolised.

It is meant to exalt the bride, to present her as a queen for a day, but to me it always felt like armour – or worse, a cage.

It was the perfect way to showcase the pressure placed on women: to appear perfect, graceful and silent, no matter how heavy the burden. Even her beauty must obey tradition. That’s the paradox I wanted to expose: how celebration can camouflage submission.

The fire represents the quiet rage – generational, internalised, contained. InMorocco, marriage is often the turning point in a woman’s life, but not always in the way it’s romanticised.

Beneath the celebrations and garments lies an expectation to conform, to serve, to stay silent. The flames at her feet symbolise the heat of that pressure – the things that cannot be spoken but are always felt.

The snake, for me, is the woman herself. Western narratives often depict Muslim women as passive, obedient, in need of saving. But I reject that completely. I believe that you only build walls or cages around something that threatens you.

The snake is not weak – it is feared. It holds power and wisdom that unsettles people. In this image, she is not afraid of the snake. Sheisthe snake: dangerous, deliberate, watching everything.

I didn’t want to stage this in a clean, controlled environment. I needed dust, wind and unpredictability. The landscape itself felt symbolic: unforgiving, exposed and yet enduring.

The series title, Dry Land, refers to the Darija termAl Bayra, meaning “barren land” – a phrase cruelly used to describe unmarried women over a certain age, as if their value disappears with time; as if they stop being fertile, not just biologically, but socially and emotionally. This work is my response to that idea.

I don’t create these images to be pretty. I create them to spark discomfort, to shift the lens – to reclaim the narrative and to make visible what has long been buried beneath brocade and silence.

Sara Benabdallahis a Moroccanvisual artist, photographer andfilm-maker based in Marrakech