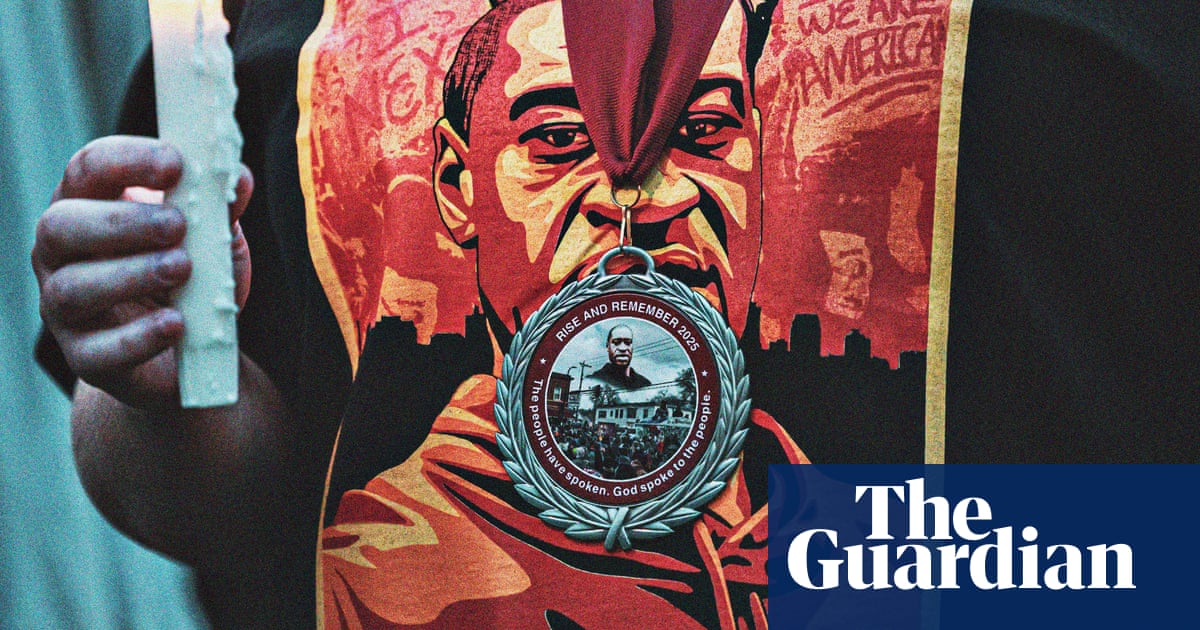

Hello and welcome to The Long Wave. This week, I reflect on theBlack Lives Matter movement, five years on from the murder of George Floyd, and trace how it changed how I think about racial justice.

I have been trying to remember how I felt when the first Black Lives Matter protests started in 2020, and it’s harder than I expected. While I have scattered recollections, the closest I can come to nailing it down is through a summary of the emotions I registered: anxiety, overwhelm followed by a determination to grasp what was happening.

My profession doesn’t help when it comes to reflecting on how history actually unfolded. One of the hazards of journalism is that often there is little time to experience and process events, only to try to capture them and analyse their significance. But another reason is that I was suspicious.

Returning towhat I wrote at the timeconfirms this. “Every few years, being Black becomes a macabre spectacle. What is usually a complicated, private identity becomes a public one. A Black man is killed by a white police officer in the United States, and suddenly the world is attuned to your race.” What is clear is that I didn’t trust the moment, and I was angry at what it took for it even to come. Did the world really need to see a man die on a pavementto realise that racism existed?

I also felt resentful that Black people were suddenly called to the spotlight, but only to perform andnarrate their experiences as a racialised people. Finally,the world was listening– but not to a whole complicated human, one who is not only defined by race but also by all the other things that make up a person. It felt out of my control, like the movement was happening about and around us, rather than to us.

It was elevating yet effacing. Theblack squares on social media, thewhite politicians taking a kneeand the myriad other instances of self-flagellation felt removed from the demands that were coalescing – to reform institutions, addresssystemic racism from healthcare to housing, and toconfront histories of enslavementand colonisationwhose legacy we still live with.

But still, I remember thinking: I’ll take it. Of course I would. How could I not? Finally, stories about theBlack experience of racialised violence and injusticewere getting attention.There was also something magnetically galvanising in how these demands mapped neatly on to different communities.

For the first time in my life, a notional concept of global Black solidarity became concrete. From the Black victims who wereshamefully mistreated during the Windrush scandalby the Home Office, to those protesting against the French police’s use ofdangerous chokeholds during arrests, to thoseremoving statues of colonial overlordswho were part of a cohort that shaped the trajectory of my birth country of Sudan – these were all my people. And so I leapt into the fray.

The immediate aftermath of BLM is sharper in my memory. It was a time of fierce argument and battle against all the directions in which the movement was being pulled. The task was to remainresilient against the backlashand the reduction of profoundly transformative demands into surface-level (even if still necessary) offers of diversity and inclusion. It was necessary, also, to stay resilient during theinevitable dissipation of attentionand allure after those first heady days.Again, there was no time to pause, and amid it all I sometimes succumbed to cynicism, perhaps in a defensive crouch. A few years ago, I would have said: “You see? I was right to be suspicious.”

Sign up toThe Long Wave

Nesrine Malik and Jason Okundaye deliver your weekly dose of Black life and culture from around the world

after newsletter promotion

What I realise now, having retreaded history, is thatthis is how all revolutions work. You cannot contain and rationalise them, and curate them to yield specific desirable outcomes. They are winds that can’t be held back.And they happen not in an abstract place but in the real world, where they will always succumb to messy and complicated countercurrents and human imperfections. They happen in larger contexts – capitalism, white supremacy, and alack of willamong progressive parties in the west to be brave and principled enough to adopt the cause of racial justice – ones that tend to colour the outcomes.

I have learned a lot in the past five years. The biggest lesson is that we don’t get to choose how revolutions unfold, and that we can obscure the small tectonic shifts by always impatiently wanting the big ones. BLM opened up the issue of racial justice in ways that can never again be closed. Whether it’s intussles about DEI, discussions aboutacademic curriculums,enslavement, colonialismand policing – the stakes have been clarified. There is no tally of wins and losses, and certainly no final score. Revolutions are not decisive in the short term but they aredefinitive in the long run.

What I can say for certain is that I am happy the revolution happened. It sharpened my understanding of how Black people have to be actively conscious of claiming theright to full personhood, while also claiming the right to Blackness on our own terms. And itconnected me to other Black peoplein their multiplicity, not just in their racial profile or experiences of racism – but also including that, when we feel like it. That feels like more than equity or inclusion – it feels like power.

Read more:

Only a third of recommendations to tackle endemic racism in UK implemented

Was the Black Lives Matter rebellion all for nothing? It may feel like that, but I have seen reasons for hope

How did 2020’s Black Lives Matter movement change the world? Our panel responds

George Floyd’s family fights for sacred ground where he took his last breath: ‘That’s my blood’

They were shot by police at the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests. ‘I came home a different person’

To receive the complete version of The Long Wave in your inbox every Wednesday,please subscribe here.