Four executions are scheduled across the US this week, marking a sharp increase in killings as Donald Trump has pushed to revive the death penalty despite growing concerns about states’ methods.

Executions are set to take place in Alabama, Florida andSouth Carolina. A fourth, scheduled in Oklahoma, has been temporarily blocked by a judge, but the state’s attorney general is challenging the ruling.

The killings are being carried out by Republican-run states where civil rights lawyers say past executions have beenbotchedandtortuousand included the killing of people who havesaidthey werewrongfully convictedand subject toracially biased proceedings.

Nineteen people have been executed in the US in 2025 so far, and if this week’s four executions proceed, along with two more scheduled for later in June, the country will see 25 executions by the end of the month – the same number of killings carried out in all of 2024. In the first five months of 2025, the US has carried out the highest number of executions in a decade year-to-date,accordingto the Death Penalty Information Center, a nonprofit that tracks capital punishment.

In Alabama on Tuesday,Gregory Huntis set to become the fifth person executed by nitrogen suffocation in the state. Last year, the state’s use of gas to kill Kenneth Smith took roughly 22 minutes, with witnesses saying hisbody violently shookduring the procedure.

Also on Tuesday, Florida is set to kill Anthony Wainwright by lethal injection, which would make him the sixth person put to death in the state this year. Florida is leading the US this year in executions as Republican governor Ron DeSantis has aggressivelypursued capital punishmentand as state legislators have sought toexpand parametersof the death penalty in ways that expertssayareunconstitutional.

Florida is also the only state to use a controversialanestheticcalled etomidate in its lethal injections despite the pharmaceutical inventorssayingit should not be used for executions. One man killed by lethal injection in the state in 2018screamed and thrashed on a gurneyas he was put to death.

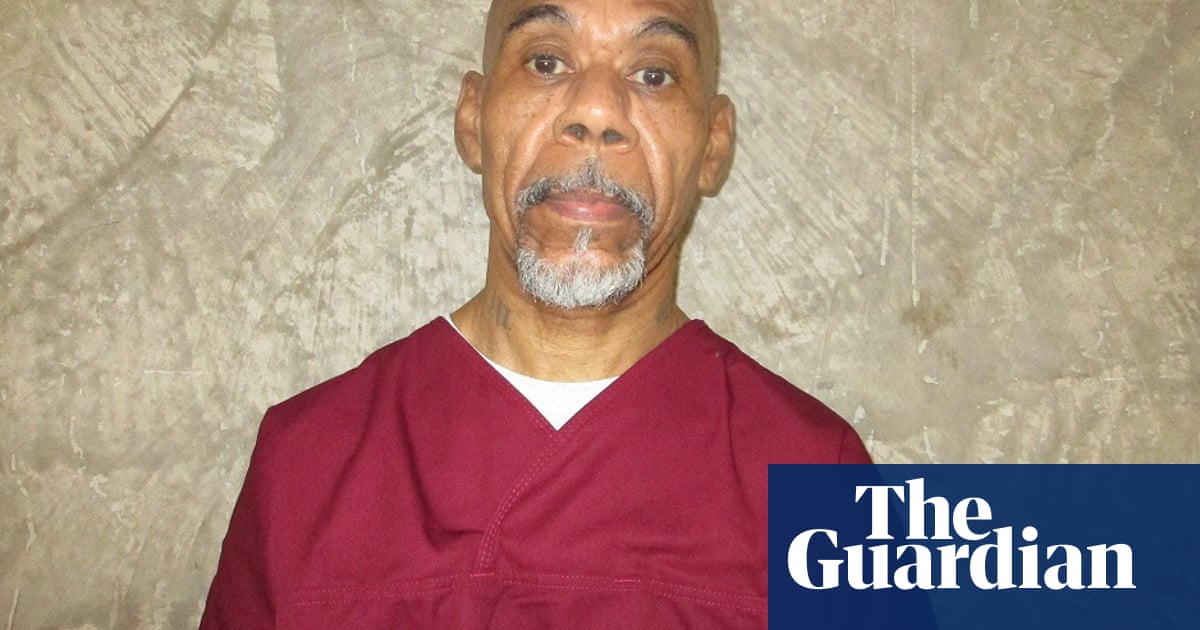

John Hanson is scheduled to be executed by the state of Oklahoma on Thursday. Hanson had been in federal prison in Louisiana serving a life sentence, and in 2022, when Oklahoma sought for him to be transferred to the state for execution, theBiden administration denied the move. This year, Oklahoma’s attorney general, citing Trump’s order, pushed to have him transferred again, and attorney general Pam Bondicomplied.

On Monday, an Oklahoma district judge sided with Hanson’s attorney and issued a stayhalting the execution, which the state’s attorney general immediately challenged to the Oklahoma court of criminal appeals. A department of corrections spokespersontold local outletsit wasmoving forwardwith plans for the Thursday execution, saying in an email to the Guardian: “We are continuing our normal process for now.”

The final execution is scheduled for Friday in South Carolina, where Stephen Stanko is set to bekilled by lethal injection. The state has been rapidly killing people after reviving capital punishment last year and directs defendants to choose between firing squad, lethal injection and electrocution. Lawyers have argued that the lethal injections haveled to a condition akin to suffocation and drowningand that the lastdeath by firing squad was botched, causing prolonged suffering.

States like South Carolina have been able to push forward with executions by passing secrecy laws that shield the identities of suppliers facilitating the killings.

“The death penalty remains unpopular and practiced by a very small number of states,” said Matt Wells, deputy director of Reprieve US, a human rights nonprofit. “In those states, you see an increased willingness to do whatever it takes to carry out executions. The result is we’re more likely to see executions go wrong.”

In one of his final acts, Joe Bidencommutedthe death sentences of 37 people on federal death row, changing their punishments to life without parole. Following Trump’s order, some local prosecutors have expressed interest in bringing state charges against commuted defendants in an effort to again sentence them to death, though they would face anuphill legal battle.

Public support for the death penalty is at a five-decade low in the US, which has seen a decrease in new death sentences, said Robin Maher, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center.

“Elected officials are setting these executions, but it does not in any way equate to increased enthusiasm for the death penalty at large,” she said.