At her home in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, Harleen Kapoor* reflects with melancholy on how, sinceNarendra Modibecame prime minister in 2014, she has spent a lot of time in the office instead of out on the powerful human rights exposés she used to work on.

Stories from some of the most deprived areas in the country were her forte. But, she says, in the climate of fear that has built up inIndiain the past decade, her media outlet has made it clear that her reports on topics such as sexual violence against lower-caste women and the harassment of Muslims are no longer welcome.

When the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata party (BJP), which rules nationally, won power in Uttar Pradesh for a second term in 2022, the outlet told her to stop travelling altogether. Its finances were already fragile, and it feared losing government advertising.

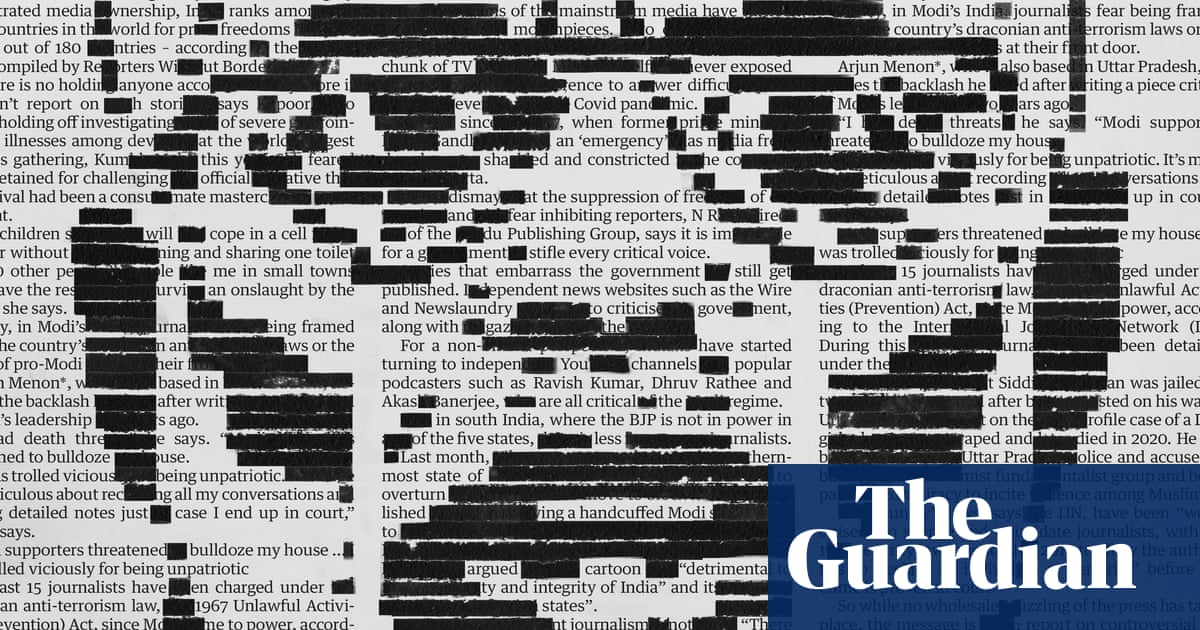

In theory, the press in India enjoys freedom. Anyone looking at the media landscape would find it vibrant, with about20,000 daily newspapersand about 450 privately owned news channels. No minister has ordered any curtailment of press freedom or freedom of expression. No formal policy of shutting down newspapers or channels has been announced. Reporters are, for the most part, free to travel.

But because of violence against journalists and highly concentrated media ownership, India is ranked among the worst countries in the world for press freedom– 151st out of 180 countries – according to theannual indexcompiled by Reporters Without Borders.

“There is no holding anyone accountable any more if you don’t report on such stories,” says Kapoor, who says she held off reporting on the many cases of severe gastrointestinal illnesses among devotees at theworld’s largest religious gathering, Kumbh Mela, this year.

She feared being detained for challenging the official narrative that the festival had been a consummate masterclass in crowd management.

“My children said, ‘how will you cope in a cell in the summer without air conditioning and sharing one toilet with 40 other people?’ People like me in small towns don’t have the resources to survive an onslaught by the police,” she says.

Today, in Modi’s India, many journalists say they fear being framed under draconian anti-terrorism laws, or the arrival of pro-Modi gangs at their front door.

Arjun Menon*, also based in Uttar Pradesh, says he received death threats after writing a piece critical of Modi’s leadership two years ago.

“Modi supporters threatened to bulldoze my house. I was trolled viciously for being unpatriotic. It’s made me meticulous about recording all my conversations and keeping detailed notes just in case I end up in court,” Menon says.

At least 15journalists have been charged under the anti-terrorism law, the 1967 Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, since Modi came to power, according to the International Journalists’ Network (IJN). Thirty-six journalists have been detained.

Siddique Kappan wasjailed for two years without trialafter being arrested on his way to Uttar Pradesh to report on the high-profile case of a Dalit girl who was gang-raped and later died in 2020. He had been picked up by Uttar Pradesh police and accused of belonging to an Islamist fundamentalist group and conspiring to incite violence among Muslims.

India’s laws,says the IJN, have been “weaponised” to silence and intimidate journalists, with the 1967 security law amended in 2019 to allow the authorities to declare an individual a “terrorist” before any crime is proved in court.

The Delhi-based independent journalistAakash Hassan, a regular contributor to the Guardian, says he has been visited at home by police and intelligence officials for his coverage of the restive Himalayan region ofKashmir, which is claimed by both Pakistan and India. He has now been banned from travelling outside India, he says, and has had his phone confiscated by police, who demanded his password.

“There are many important stories I have wanted to do, and I should be doing, but fears for my safety and that of my family have stopped me. It’s very scary to know that any number of draconian laws can be used to jail journalists. Then you can wait years for a verdict,” says Hassan.

Modi and the BJP are not the first in India to try to suppress media freedom, says the journalist Paranjoy Guha Thakurta. Earlier governments also tried, including the Congress party, now the main opposition. Under a Congress government in 2012, the cartoonist Aseem Trivediwas arrestedfor depicting parliament as a toilet.

The difference, says Thakurta, is that the Modi regime has “weaponised law-enforcing agencies to target not only its political opponents but several independent journalists who have not kowtowed to the right wing”.

Large sections of the mainstream media appear to have been turned into subservient mouthpieces. Modi himself has never exposed himself to a press conference to answer difficult questions, not even during the Covid pandemic.

“Never since 1975-77, when former prime minister Indira Gandhi imposed an ‘emergency’, has media freedom been so shackled and constricted in the country,” says Thakurta.

While dismayed at the suppression of freedom of expression and the fear inhibiting reporters, N Ram, director of the Hindu Publishing Group, says critical voices remain. Stories that embarrass the government do still get published. Independent news websites such asthe WireandNewslaundrycontinue to criticise the government, along with magazines such asthe Caravan.

For a non-official perspective, Indians have started turning to independent YouTube channels and popular podcasters such as Ravish Kumar, Dhruv Rathee and Akash Banerjee, who are all critical of the Modi regime. And in southern India, where the BJP is not in power in any of the five states, there is less fear among journalists.

Last month,Vikatan, a news website in the southernmost state of Tamil Nadu, managed to get a court to overturn the government’s move to block it after it published a cartoon showing a handcuffed Modi sitting next to Donald Trump following news of the deportation of Indian immigrants from the US. The Modi government’s lawyer had argued that the cartoon was “detrimental to the sovereignty and integrity of India” and its “friendly relations with foreign states”.

Ram says independent journalism is not dead. “There remain spaces and voices that resist suppression and I think we will see more people standing up to pressure.”

- Names have been changed to protect identities