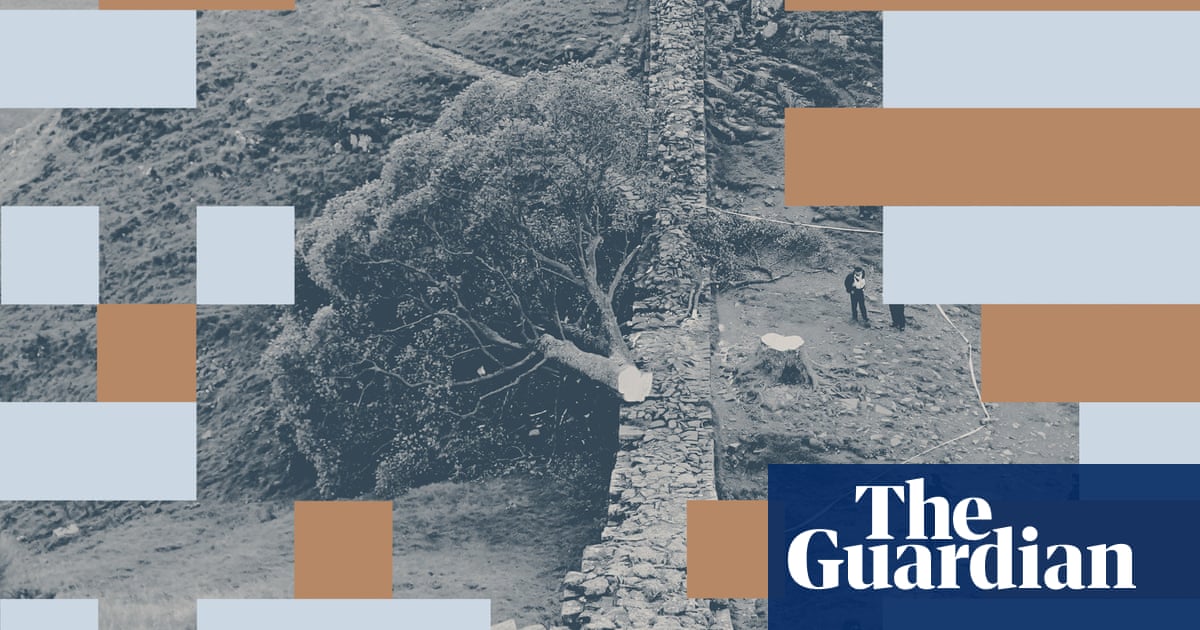

Iwas moved to read of the grief expressed by so many at the brutal felling of the Sycamore Gap tree. I found it surprising. Not the crime itself: I know well the unconscious drive we all have within us to destroy good things – the most valuable, the most beautiful, the most life-affirming things. What took me by surprise was the capacity that so many people found within themselves to express their devastation and anger at this painful loss, not only to us as individuals, but as a nation.

On the day the perpetrators were found guilty, I was reeling in my own private grief. I’d just read a different news story that told of another brutal cutting-down: again the destruction of something beautiful and valuable with deep roots, that stood for growth and possibility and life. The article, on this website, told how among other “savings”, talking therapies services are to be cut “as part of efforts by England’s 215 NHS trusts to comply witha ‘financial reset’”.

As a patient in psychoanalysis that I pay for privately because I am privileged enough to be able to afford it; as a psychodynamic psychotherapist working in theNHSbecause I passionately believe that people should have access to good, sustained mental health treatment regardless of their means; and as your columnist writing about how to build a better life – I find this to be morally wrong.

Just as I was not surprised by the felling of the Sycamore Gap tree, I am not surprised by these further cuts to talking therapy on the NHS. The flesh is so thin on the bone already, there is precious little now to cut, with patients facing the (bad) luck of the draw of patchy, postcode lottery-style provision. Many of us as individuals have a tendency to diminish our own mental anguish – to feel that physical pain is somehow more worthy. This is why it is unsurprising that we tolerate such meagre offerings of sustained psychotherapy on the NHS. It is why we have to have a law that mental health and physical health should be treated with parity of esteem – because deep down, we do not do this within ourselves.

That law, incidentally, is theHealth and Social Care Act 2012, which states it is theSecretary of State for Health’s duty to “continue the promotion of a comprehensive health service designed to secure improvement […] in the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of physical and mental illness”. How can he possibly fulfil this duty if the already limited offer of psychotherapy is reduced even further?

Whether talking therapy services are scrapped altogether, or treatments are shortened and cheapened and replaced with “interventions”, it seems important to see the truth of what is happening here. There will be cuts to psychotherapy. Psychotherapy in its different modalities is a potent treatment that has been proven again and again, in study after study and in patient after patient, to be effective for many people suffering with mental illness – and, in the case of sustained psychodynamic psychotherapy, to grow more effective over time after treatment ends. Patients can use it and get better. Do we understand this? That psychotherapy works? Of course it doesn’t always work, and it is not always indicated for everyone – like any other treatment. But for many, it works. It saves lives. It keeps people out of hospital. It enables people to get back into work. It can repair relationships. It can restore self-respect. It can allow people to stand tall when they have previously had to drag themselves along the ground. It is a treatment that works, and it is being cut, so people will have even less chance of being offered it than they do now.

We need to find within ourselves the kind of anger and sadness at cutting down our mental health services that some have found within themselves at the cutting down of the Sycamore Gap tree. This tree found its home in an empty hollow and grew strong and true and beautiful. Psychotherapy can help people do that too. And what will fill the gap left when psychotherapy is cut down? The usual things people turn to when they are struggling and they feel hopeless, uncared-for and forgotten – none of them good. Suicidality; addiction; relationship and family breakdown.

If we want to build a better life, for ourselves and our families and our fellow citizens, we need to do something about this. We need to fight for our cause; we need to protest in the streets and bring legal challenges and write (politely and firmly) to our MPs. We need to demand theHealthSecretary fulfil his responsibilities outlined by the Health and Social Care Act 2012. We need to stand up and make it politically impossible for this government that talking therapies provision be further diminished; the NHS must offer psychotherapy treatment for anyone who needs it and who can use it.

Receiving and offering psychotherapy has taught me that we all have it in us to cut down and destroy beautiful things – but we also have it in us to come together in our grief, to repair, to help each other, to do good things, to stand up when we see that something is deeply morally wrong. That is how we build a better life not only for ourselves but also for each other.

Moya Sarner is an NHS psychotherapist and the author ofWhen I Grow Up – Conversations With Adults in Search of Adulthood

Do you have an opinion on the issues raised in this article? If you would like to submit a response of up to 300 words by email to be considered for publication in ourletterssection, pleaseclick here.