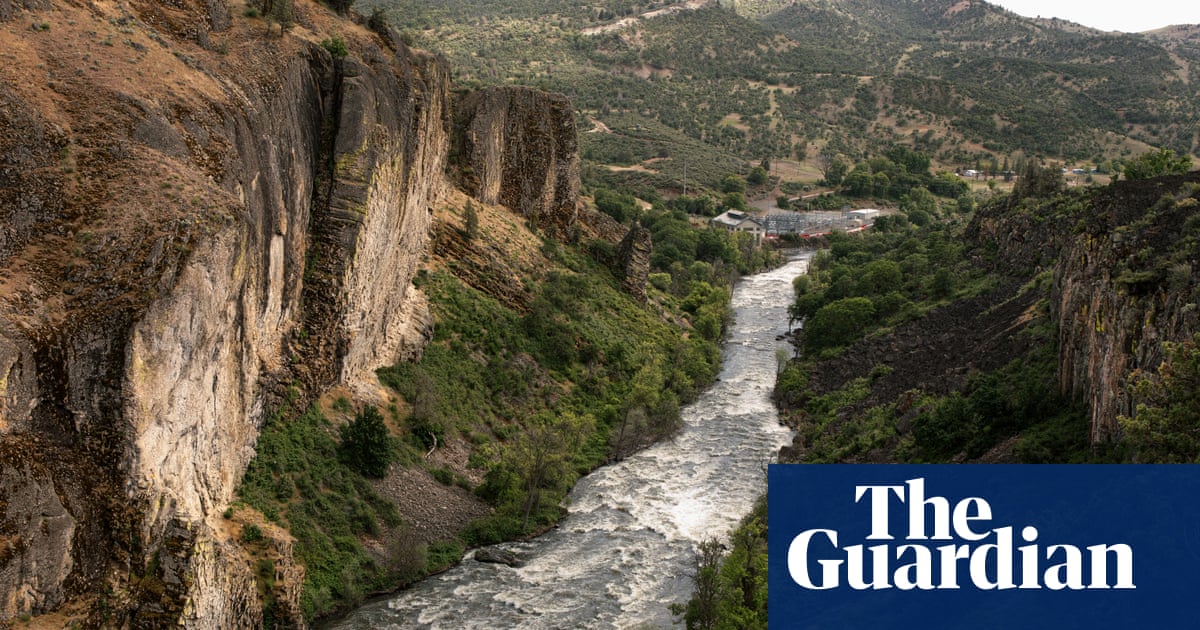

Bill Cross pulled his truck to the side of a dusty mountain road and jumped out to scan a stretch of rapids rippling through the hillsides below.

As an expert and a guide, Cross had spent more than 40 years boating the Klamath River, etching its turns, drops and eddies into his memory. But this run was brand new. On a warm day in mid-May, he would be one of the very first to raft it with high spring flows.

Last year, the final of four hydroelectric dams on the Klamath River were removed in thelargest project of its kind in US history. Forged through the footprint of reservoirs that kept parts of the Klamath submerged for more than a century, the river that straddles the California-Oregon border has since been reborn.

The dam removal marked the end of a decades-long campaign led by the Yurok, Karuk and Klamath tribes, along with a wide range of environmental NGOs and fishing advocacy groups, to convince owner PacifiCorp to let go of the ageing infrastructure. The immense undertaking also required buy-in from regulatory agencies, state and local governments, businesses and the communities that used to live along the shores of the bygone lakes.

As the flows were released and the river found its way back to itself, a new chapter of recovery – complete with new challenges – emerged.

Among the questions still being answered: how best to facilitate recreation and public connection with the Klamath while recovery continues. There are hopes for hiking trails, campgrounds and picnic spots. A wide range of stakeholders are still busy ironing out the specifics and how best to define the lines between private and public spaces.

It’s a delicate process. Not just the ecology is being restored; the Indigenous people whose ancestors relied on the river for both sustenance and ritual across thousands of years are also renewing their relationships with the land.

More than 2,800 acres, some of which emerged from under the drained reservoirs after the dams came down,will be returned to Shasta Indian Nation, a tribe that was decimated when construction on the dams started in the early 1910s. Ready to be stewards, they are also now navigating their role as landowners in a recreation region.

On 15 May, the first opening day for new access sites on the Klamath, visitors got the first real glimpse of the extensive restoration efforts since demolition began in 2023. It also served as an early trial for how the public and an eager commercial rafting community might engage with the river and the landscapes that surround it.

As the sun broke through a week of cloudy weather that morning, rafters readied their gear near an access now bearing the traditional name in the Shasta language, K’účasčas (pronounced Ku-chas-chas).

“If we were here a little over a year ago, we would be standing on the edge of a reservoir,” said Thomas O’Keefe, the director of policy and science for American Whitewater, as he helped Cross and Michael Parker, a conservation biologist, ready their boat for a stretch of river above where the Iron Gate dam once stood. The Guardian joined them to try the section on opening day.

O’Keefe has played a pivotal role in bridging recreation and restoration on the river. He hopes connecting people to the landscapes will encourage future care for them.

“The vast majority of people want to do the right thing,” O’Keefe said, describing the extreme care taken towards ecologically and culturally sensitive areas. “We want to make sure we can define where that can happen.”

There is still a lot of work left to do. Rustic roads that lead to the river’s edge are minimally paved and laden with potholes. It’s not immediately clear where visitors should park. Finishing touches are still being added on signs and infrastructure – from put-ins to picnic tables – with the completion of five new public recreation sitesplanned for 1 August.

And for rafters, of course, the river itself must be relearned. Roughly45 continuous mileswere unleashed between the Keno and Iron Gate dams. Rapids long-dependent on artificial surges from the hydropower operations are at last being fueled by natural conditions.

“We are kind of writing the book on it,” said Bart Baldwin, the owner of Noah’s River Adventures, a commercial outfit out of Ashland,Oregon, who has taken guests downriver for decades. While he admits the releases from the dams made for “world-class” rapids, he says the loss has created new opportunities.

“The scenery is stunning and I think it’s going to be special.”

The waters of the Klamath have burst back to life in recent weeks, spurred by melt-off from strong winter storms. The Iron Gate run bumps and sways through a mix of class II and class III rapids, enough for a fun ride that’s manageable for most experience levels. Upriver, theexciting and challenging K’íka·c’é·ki Canyon runwinds through more than 2.5 miles of class IV rapids, beckoning those with more expertise.

As he called out paddling orders to navigate his boat’s small crew through splashy sections, Cross was relieved. In the years before the dams came out, he’d worked to outline the new river and its whitewater potential,armed with historical topographic maps, old photos and bathymetric data that showed depth and underwater terrain. Rooted in science, it requires a bit of guesswork. The volcanic geology here often comes with surprises.

“I spent the first six months sweating bullets watching the water recede and the channel scour and wondering if there was going to be a waterfall I didn’t predict,” he said.

Even with strong flows, there was space to breathe between more challenging sections. There were spots to beach boats for a picnic lunch, places to quietly float through the vibrant scenery.

Vestiges of the recent past are still visible. Gradients of green shroud a scar left by the high-water mark of the reservoir. Columns of dried mud, remnants of the 15m cubic yards of sediment held behind the dams, are clumped along the river’s edge.

But there are also signs of nature’s resilience. Swaying willows stand stalwart from the banks. Behind them, rolling hills splashed with orange and yellow wildflowers and ancient basalt pillars stretch to the horizon. Far from the hum of highway and roads, the silence here is broken only by the purr of the river as it rolls over rocks, accented with eagle calls or chattering sparrows who have already claimed sites along the water for their nests.

Years before the dams were demolished, as teams of scientists, tribal members and landscape renovation experts tried to envision how recovery should unfold, there wasn’t a guidebook to go by. There weren’t records for how the heavily degraded ecosystems should look or function.

“Creating the mosaic we are currently seeing out there has been a work of educated estimation,” said Dave Coffman, a director for Resource Environmental Solutions (RES), the ecological recovery company working on the Klamath’s restoration. “There’s nothing in that watershed that hasn’t been touched by some sort of detrimental activity.”

In less than a year’s time, a dramatic reversal has taken place. Some spots have bounced back beautifully. Others had to be carefully cultivated to mimic what could have been if the dams never disrupted them. Native seeds were cast across the slopes, some by hand and others from helicopters. Heavy equipment trucked away mounds of earth. Invasive plants were plucked from around the reservoir footprint before they could spread across the barren ground.

“We are giving nature the kickstart to heal itself,” said Barry McCovey Jr, the fisheries department director for the Yurok tribe. What he calls “massive scars” left by the dams “aren’t going to heal overnight or in a year or in 10 years”, he added. Giving the large-scale process, time will be important – but a little help can go a long way.

In late November last year,threatened coho salmon were seen in the upper Klamath River basinfor the first time in more than 60 years. Other animals are benefiting, too, including north-western pond turtles, freshwater mussels, beavers and river otters.It took mere months for insects, algae and microscopic features of a flourishing food web to return and sprout. “It’s amazing to see river bugs in a river,” he said. They are good indicators of water quality and ecosystem health.

It might seem like a happy ending. McCovey Jr said it’s just the beginning. “We are going to have ups and downs and it will take a long time to get to where we want to be,” he said.

Ongoing Yurok projects will focus on making more areas “fish-friendly” and closely monitoring aquatic invertebrates in coordination with the other tribes, researchers and advocacy organizations, and the Klamath River Renewal Corporation thatwas created to oversee the project.

There are also far-flung parts of the watershed they are still working to restore. Close to47,000 acres of ancestral Yurok homelands in the lower Klamath basinwill be returned to the tribe this year after being owned and operated for more than a century by the industrial timber industry. Considered the largest land-back conservation deal in California history, the work there will complement and benefit from what’s being done upriver.

Even as recovery on the riverremains perhaps at its most fragile, most people who have been part of this enormous undertaking are looking forward to welcoming the public.

“I think one of the biggest fears of this project is that it wouldn’t work,” Coffman said. “I am excited for more folks to get out here and see what we are capable of.”

The work goes beyond the water line. The lands that hug this river have had their own transformation, along with the people who once called them home.

“People are really focused on dam removal and fish and recreation – and those are all great things – but it is a very personal story for us,” said Sami Jo Difuntorum,cultural preservation officer for the Shasta Indian Nation. As the tribe returns to their ancestral lands, they are envisioning ways to introduce themselves to a largely unfamiliar public.

Their story is laced with tragedy, but also resilience. Shasta Indian Nation is not federally recognized, largely because they were massacred in the mid-19th century when gold-seeking settlers poured into the region. Their villages and sacred lands were drowned in the damming of the river. But the people tied to these lands have largely remained close by; many still reside in the county.

As the waters of the reservoirs receded, it revealed a place held at the heart of their culture for thousands of years.

“The return of our land is the most important thing to happen for our people in my lifetime, for the generation before and the generation ahead,” Difuntorum said, standing on a quiet overlook watching the river course through the sacred K’íka·c’é·ki Canyon. This steep basalt chasm was left dewatered while the river was rerouted to the hydroelectric plant.

“There are so many things we are learning, like how to coexist as future landowners with the whitewater community, the local community, the fishermen – and then all the tribes,” she added. “It’s a lot – but it’s all good stuff. It’s huge for our people.”

Looking ahead, plans are being made both for public use and for tribal reconnection. There will be access trails across their lands and efforts to plant traditional medicinal and ceremonial plants. Old buildings that provided electricity from the plant will be converted to an interpretive center. Places have been picked for sweat lodges, an official tribal office and the area where the first salmon ceremony will be held in more than century. Difuntorum’s grandsons – ages nine and six – will be dancing in that ceremony this year.

For the tribe, reconnecting to the river has provided an opportunity to reconnect to their culture and history.Part of reconnecting comes through reintroducing their language. James Sarmento, a linguist and tribal member, is helping Shasta people learn and use pronunciations for recovered places as they were once known along with the stories of creation tied to them. The public will learn them, too.

“It’s about making a relationship and having conversations with the land,” Sarmento said. “These are landscapes that we are not only working to protect – we are working to speak their names out loud.”

The darker moments in the tribe’s history live on. Remnants of the now-inoperable hydroelectric plant still sit solemnly on the embankment: coils of metal, enormous pipes, nests of wires that connect to nothing. A cave, tucked into the steep slopes among ancient lava fields where 50 or so Shasta people sought refuge in the mid-1800s, still bears the violent marks of a miners’raid that left five people, including women and children dead.

Difuntorum said it used to be hard for her to see it all. “I don’t feel that now,” she said. “Of all the places I have been in the world, this is where I feel the most me – out here at the water.”

Cross, O’Keefe and Parker pulled up their paddles to ease into the final float of the run, gliding through the channel that once propped up the Iron Gate dam. Overhead, an osprey settled into its nest with a large fish as a throng of small birds scattered into the cloudless sky.

There are sure to be challenges ahead. The climate crisis has deepened droughts and fueled a rise in catastrophic fire as this region grows hotter. Habitat loss and water wars will continue as city sprawl, agriculture and nature increasingly come into conflict.

For now though, the river’s recovery is a hopeful sign that a wide range of interests can align to make a positive change, even in a warming world.

“I never thought I would see the run under reservoirs be revealed,” Cross said, smiling as he packed up his boat. As a new chapter begins, the Klamath has already become a story of what’s possible, fulfilling the hopes that the project could inspire others.

And, after decades of advocacy and years of work, “we have salmon and beaver and poppies,” he said. “This river will go on forever.”