Mary Annette Pember will publish her first book, Medicine River, on Tuesday. She signed to write it in 2022 but feels she really started work more than 50 years ago, “before I could even write, when I was under the table as a kid, making these symbols that were sort of my own”.

A citizen of the Red Cliff Band of Wisconsin Ojibwe, Pember is a national correspondent forICT News, formerly Indian Country Today. In Medicine River, she tells two stories: of the Indian boarding schools, which operated in the US betweenthe 1860s and the 1960s, and of her mother, her time in such a school and the toll it took.

“My mother kind of put me on this quest from my earliest memory,” Pember said. “I’ve always known I would somehow tell her story.”

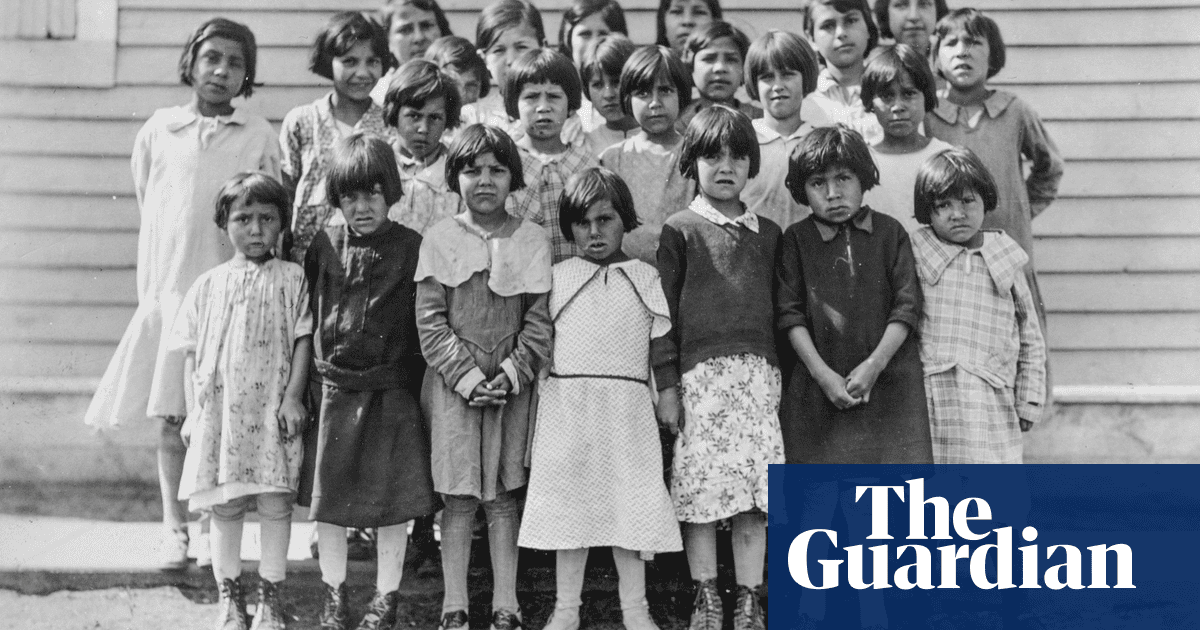

More than 400Indian boarding schoolsoperated on US soil. Vehicles for policies of assimilation, perhaps better described as cultural annihilation, the schools were brutal by design. Children were not allowed to speak their own language or practice religions and traditions. Discipline was harsh, comforts scarce. Asdescribedby Richard Henry Pratt, an army officer and champion of the project, the aim was to “kill the Indian in him, and save the man”.

In the 1930s, Pember’s mother, Bernice Rabideaux, was sent with her siblings toSt Mary’s Catholic Indian boarding school, on the Ojibwe reservation in Odanah, Wisconsin. Bernice was marked for life. On the page, Pember describes how as a young child she responded to her mother’s dark moods by hiding under the kitchen table, making her symbols on its underside. But she also writes about how her mother’s “terrible stories” about the “Sisters School”, about psychological and physical abuse, helped form a bond that never broke.

Pember kept writing. A troubled child, she “sharpened a lead pencil into a dagger-like point and wrote microscopic messages and insults to my family on the wall next to the stairs” of the family home in Chicago. Later, she became a reporter.

“Writing is so visceral for me,” she said. “I still like writing with a really sharp pencil, I like the sound of it in my notebooks, and I keep them with me all the time. It always hits me when I’m really tired, and the last thing I want to do is write things down, and that’s when I have to do it … It’s just such a part of me, I don’t question it.

“There was a lot of drama in my house. All these things were going on. Of course, they weren’t explained to me. They would sort of lower their voices if they knew I was around. And I just hated being an outsider. I wanted to know what was going on.”

Medicine River is an attempt to explain. To most, its story will be unfamiliar. If recent years have seen a shift in US awareness of the boarding schools and their legacy, that is in large part due to events in Canada, wherediscoveries of unmarked gravesat sites of such institutions prompted anational reckoningof sorts.

“We were the model from which Canada drew,” Pember said. “We predated them by quite some time, and we had far more schools. It had an impact on a far greater number of children. But for some reason we just remain stubbornly ignorant of it here in the United States. They were horrible places in which children were brutalized. And of course it wasn’t just the schools. The schools were part of a greater federal assimilationist agenda.

“If they had just done the schools to us, it would not have been so bad. But I always think of it as this triple whammy that happened to Native people in the 19th century. It wasremoval[forced relocation west], thenallotment[dividing lands collectively held], then taking the kids away. It was a concerted attack on our culture, our language and our holdings. That was what it was really about. They wanted our land.

“The public was averse to outright extermination, so it was framed as a humanitarian policy. I think it is really important to view boarding schools in that context.”

Pember’s investigations led her to dark places. Noting that in other spheres the Catholic church has been forced to reckon with sexual abuse by priests, she said a moment of truth regarding Native boarding schools may yet come – while pointing to milestones already passed includingreportingby Dana Hedgpeth and others for the Washington Post, a class actionlawsuitin western states, and similareventsin Alaska.

“Native people were not really viewed as actually human,” Pember said. “One of the surprising things I learned in researching the book, was the power of the eugenics movement. I mean, this was not peripheral hogwash. They were teaching this at Harvard. The leaders of the era … supported this whole notion of eugenics. They were using phrases like ‘the final solution’. They stopped short of advocating euthanasia but there were 30 states that allowed involuntary sterilization of people who were considered feeble-minded or in some way racially inferior … I had not realized how foundational that was, to the way the relationship between the federal government and Native people evolved.”

For Pember, publication day will not be without a certain irony. As Medicine River was written, the federal government finally engaged, to some extent, with the Indian boarding schools and their lasting harms. Last year brought aninvestigative report, identifying at least 973 student deaths (the Postfoundmore than 3,100), and apresidential apology, delivered by Joe Biden alongside Deb Haaland, the first indigenous secretary of the interior. But as Medicine River comes out,Donald Trumpis back, assaulting federal agencies with staffing and budget cuts, seeking to obliterate recognition of America’s racist past.

Sign up toFirst Thing

Our US morning briefing breaks down the key stories of the day, telling you what’s happening and why it matters

after newsletter promotion

“Things are so wild and uncertain,” Pember said. “We’re all just being pulled back and forth, every single day.

“We’re still trying to figure out the impact of these things [Trump has] done, because Indian country runs on all of these disparate grants from agencies … the US Department of Agriculture gives so many grants to Indian country, for example, and then there’s various sub-agencies and organizations within that. Unlike mainstream America, we have no tax base, and so we don’t really have good, sustainable infrastructure. So we’re trying to piece it together.

“I[n] the Bad River tribe, where my mom is from, the librarian is gone now. She lost her funding, under some real obscure agency. And that was so sad. They just recently got it, and they were really feeling they were sitting pretty, and now that’s gone.”

Hope remains. TheTruth and Healing Commissionon Indian Boarding School Policies in the United States Act, a bipartisan measureintroducedin 2021, is not dead yet. Lisa Murkowski, an Alaska Republican senator more independent-minded than most, hastaken it up. Pember noted that if such a commission is formed, it will not have subpoena power, perhaps necessary for co-operation from the Catholic church.

Pember is determined to keep the Indian boarding schools in the public eye.

“The goal is to record as much as possible the stories that people have,” she said. “To say, ‘Yes, this happened to you. Let’s document this.’”

Describing research atMarquette University in Milwaukee, in the archives of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions, she said: “The big thing is to make these records available to people. I can tell you how powerful it is just see your relative’s name printed. To see my mom’s name and my uncles and aunts and my grandmother and grandfather, to see their names on these rosters … was just something really powerful. It said: ‘This happened, and there’s no workaround. There’s no way people can apologize it away. This did happen.’ That’s uniquely powerful.”

Medicine River is out in the US on 22 April