Alison Bechdel emerged in the 1980s with Dykes to Watch Out For, a groundbreaking weekly strip that featured a group of mostly lesbian friends. Since then, her acclaimed graphic novels have focused mainly on herself and her family.Fun Homein 2006 (exploring her closeted, funeral-director father’s suicide and her coming out) was followed byAre You My Mother?(psychoanalysis and her relationship with her mother) andThe Secret to Superhuman Strength(her compulsive exercising, from karate and crunches to snowshoeing).

These three erudite, pensive and observant works spend most of their time looking back. Where the modern Bechdel is present, she is mostly sketching, editing and narrating her past, and contemplating how everyone from Jack Kerouac and Virginia Woolf topaediatrician Donald Winnicottcan help her shed light on it.

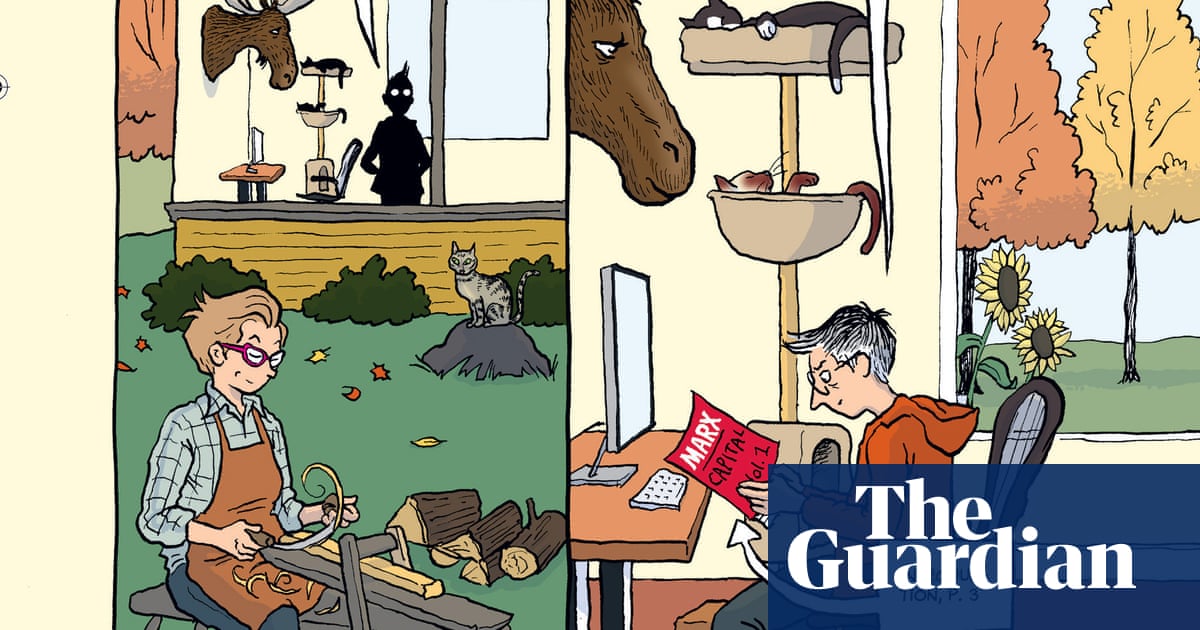

In Spent, by contrast, we meet an Alison Bechdel who lives largely in the present. She writes and draws in rural Vermont, campaigns for progressive causes and hangs out with her friends and her wife, Holly. Yet this book-Alison is not quite the real Bechdel. In Spent, Alison’s father was a taxidermist, not a mortician; Bechdel’s two brothers have been replaced by aMaga-loving sister. In our world, Fun Home has been made into a Tony-winning musical and is being (slowly) developed into a movie starring Jake Gyllenhaal. The equivalent in Spent is Death and Taxidermy, a graphic memoir whose very loose TV adaptation (dragons and cannibalism feature, alongside Aubrey Plaza and Benedict Cumberbatch) is on to its third season.

The book-Alison has mixed feelings about its success, but the royalties help fund the pygmy goat sanctuary she runs with Holly, and give her the leeway to prevaricate as she plans a new work: $um, an accounting of money and her life, with a little help from Karl Marx. Progress is slow: headlines about Trump’s first term blare from her device screens, the goats are grabbing every opportunity to breed, Holly is increasingly keen to film everything for her social feeds and Covid has the world in its grip. America is atomised, with “a zillion streaming options with six people tuned into each of them”, Alison says. “No wonder the country’s a mess.”

Yet Spent is anything but a book about a writer’s lonely lot. Alison’s liberal community bustles with gossip and life. There are vets to befriend, new neighbours to meet, anticolonial Thanksgiving dinners to attend and speeches to give against book banning. Just down the road, her friends Ginger, Lois, Sparrow and Stuart share a house, this quartet – in another metafictional twist – having wandered over from the panels of Dykes to Watch Out For.

Spent, then, feels less like a fictionalised autobiography and more a gathering of threads from Bechdel’s life and work, a celebration of and a rumination on where she has landed in late middle age, and how some of her fictional creations might live alongside her.

That doesn’t mean first-time readers won’t enjoy it. Bechdel’s acutely observant line drawings – here enriched with warm colour by the real-life Holly – lend themselves wonderfully to the alternately comfortable, intimate and awkward interactions of her cast as they gather around tamari-roasted turnips and fennel flambé to shoot the breeze. There’s always been a spark to Bechdel’s work, despite its often serious themes, and writing about herself from a greater fictional distance seems to have given her more room to have fun. Dramas and mishaps unspool with a lightly comic charm that belies the darkness in the world outside, from Alison’s optimistic side-hustle (she pitches a reality TV show based on ethical living) to Sparrow and Stuart’s experiment as a throuple with old friend Naomi (a vegan purple dildo is delivered with a wink by a FedEx driver).

Yet it’s longtime fans who will get the most from Spent. There’s a real joy to seeing characters return, their shapes a little baggier, their hair greyer, but their spirits the same. If you’ve treasured sharing Bechdel’s days spent hunched over her diary as a pale and anxious child, or cycling up theAdirondacksas a fitness-mad thirtysomething, it’s poignant to meet an Alison whose fierce self-analysis has mellowed a little. There’s a pathos, too, in seeing once-young radicals engage with a younger generation, in the form of Sparrow and Stuart’s daughter JR, who has returned to Vermont after the collapse of her polycule.

Spent isn’t perfect. At times Alison’s world, with its “Shmetflix” and “Schmamazon” and “sage and sawdust” gluten-free stuffing, seems broad pastiche. There are stretches where you feel like you’re watching comfortably off semi-retirees cosplaying as agricultural workers. Yet while Spent may lack some of the raw power of Bechdel’s earlier work, this wise and playful tale has deep roots. On a flight back from pitching half-interested streaming networks about her reality TV show Alison soars over the “intriguingly wrinkled landscape of the south-west”, asks for a pencil and starts drawing over a TV script, the “rasp of graphite on paper … opening the flat page into another dimension”.

It’s a neat epiphany and a lovely summary of the craft of comics, and it feels thoroughly earned. By the end of Spent, Alison has learned that she can’t do everything, but that perhaps doing something – and being in the moment with people you love – is enough. It’s an almost cosy conclusion, undercut by what we know but the book-Alison does not: that Trump will return, not long after her account has finished. Will Alison keep her newfound joie de vivre? I hope we get to find out.

Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel is published by Jonathan Cape (£20). To support the Guardian, order your copy atguardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.