It has long been assumed that William Shakespeare’s marriage to Anne Hathaway was less than happy. He moved to London to pursue his theatrical career, leaving her in Stratford-upon-Avon and stipulating in his will that she would receive his “second best bed”, although still a valued item.

Now a leading Shakespeare expert has analysed a fragment of a 17th-century letter that appears to cast dramatic new light on their relationship, overturning the idea that the couple never lived together inLondon.

Matthew Steggle, a professor of early modern English literature at the University of Bristol, said the text seemed to put the Shakespeares at a previously unknown address in Trinity Lane – now Little Trinity Lane in the City. It also has them jointly involved with money that Shakespeare was holding in trust for an orphan named John Butts.

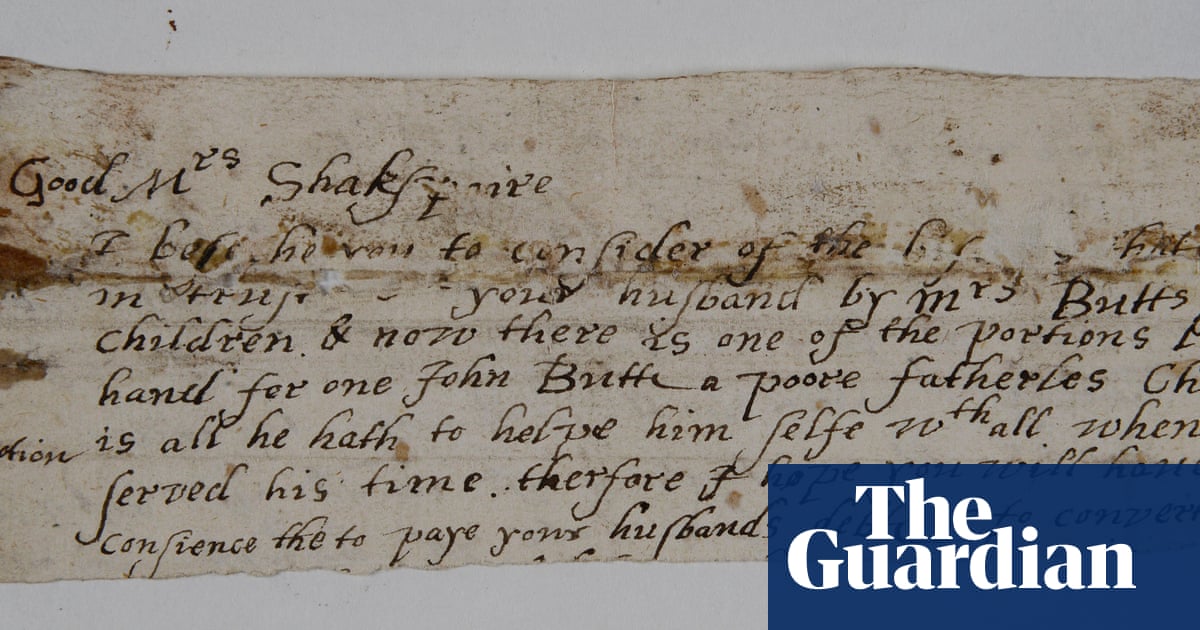

Addressed to “Good Mrs Shakspaire”, the letter mentions the death of a Mr Butts and a son, John, who is left “fatherles”, as well as a Mrs Butts, who had asked “Mr Shakspaire” to look after money for his children until they came of age. It suggests the playwright had resisted attempts to pay money that the young Butts was owed.

Steggle said: “The letter writer thinks that ‘Mrs Shakspaire’ has independent access to money. They hope that Mrs Shakspaire might ‘paye your husbands debte’.

“They do not ask Mrs Shakspaire to intercede with her husband, but actually to do the paying herself, like Adriana in The Comedy of Errors,who undertakes to pay a debt on her husband’s behalf, even though she was previously unaware of it: ‘Knowing how the debt grows, I will pay it.’”

Steggle added: “For about the last 200 years, the prevailing view has been that Anne Shakespeare stayed in Stratford all her life and perhaps never even went to London.”

This document, which refers to the couple who “dwelt in trinitie lane”, suggests that she did spend significant time with her husband in the capital.

The fragment was preserved by accident in the binding of a book in Hereford Cathedral’s library. Although it was discovered in 1978, it has remained largely unknown because “no one could identify the names or places involved”, Steggle said.

Crucial evidence includes the 1608 book in which the fragment was preserved, Johannes Piscator’s analyses of biblical texts. It was published by Richard Field, a native of Stratford, who was Shakespeare’s neighbour and his first printer.

Steggle said that it would be a “strange coincidence” for a piece of paper naming a Shakspaire to be bound, early in its history, next to 400 leaves of paper printed by Field, “given Field’s extensive known links to the Shakespeares”.

John Butts seems to have been serving an apprenticeship because the letter mentions “when he hath served his time”. Scouring records from the period 1580 to 1650, Steggle found a John Butts, who was an apprentice, fatherless and in the care of his mother.

He also unearthed a 1607 reference to a John Butts in the records of Bridewell, an institution whose tasks included the disciplining of unruly apprentices. A document told of “his disobedience to his Mother” and that he was “sett to worke”.

Steggle found John Butts in later records, placing him in Norton Folgate, outside the city walls, and living on Holywell Street (Shoreditch High Street today), home to several of Shakespeare’s fellow actors and associates.

It was an area in which Shakespeare worked in the 1590s, first at theTheatrein Shoreditch, the principal base for the Lord Chamberlain’s Men throughout those years, and then at its near neighbour, the Curtain theatre. Shakespeare’s lifelong business partners, the Burbages, were involved in innkeeping and victualling nearby.

Steggle said: “The adult John Butts, living on the same street as them, working in the hospitality industry in which they were invested … would very much be on the Burbages’ radar. So Shakespeare can be linked to Butts through various Norton Folgate contacts.”

If the writing on the back of the letter – in another hand – was written by Anne, the words would be “the nearest thing to her voice ever known”, he noted.

The research is being published inShakespeare, the journal of theBritish Shakespeare Association, on 23 April, the anniversary of his birth.

Steggle writes: “For Shakespeare biographers who favour the narrative of the ‘disastrous marriage’ – in fact, for all Shakespeare biographers – the Hereford document should be a horrible, difficult problem.”