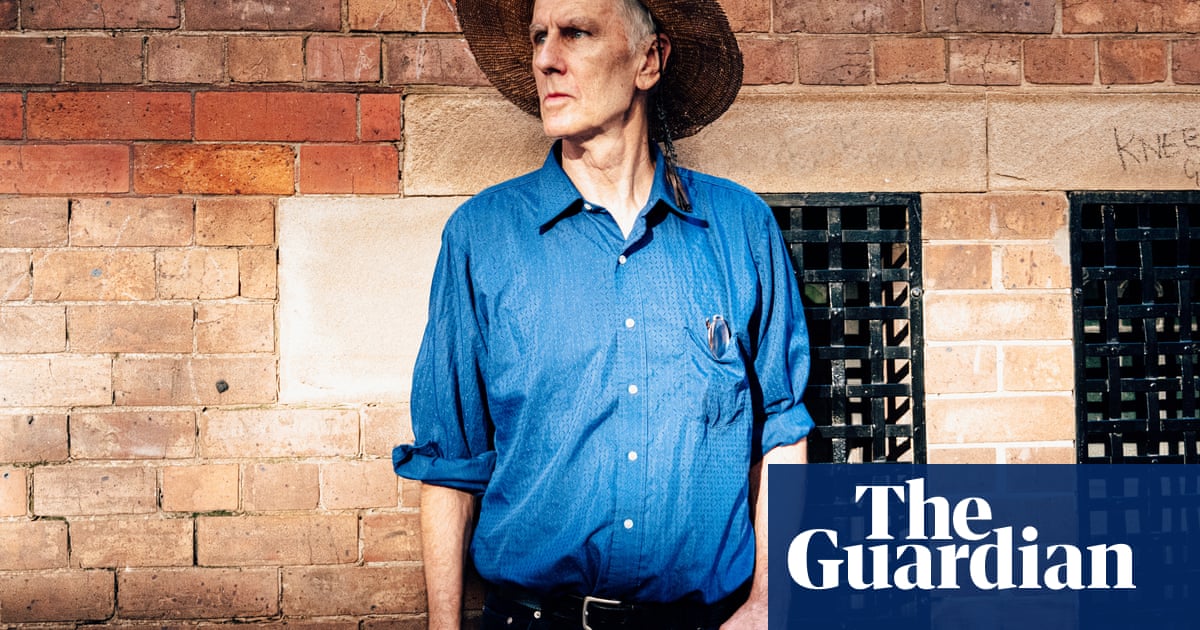

When I meet former Go-Between Robert Forster at a cafe in the centre of Brisbane for a walk around his home town, it’s no surprise to see a book on the table in front of him. It isThe Café With No Name, by Austrian novelist Robert Seethaler – a gift for his wife, Karin Bäumler.

Forster picked it up, somewhat reluctantly, from a chain store. A great indie bookshop, he says, is “the one thing that I really miss in Brisbane – the thing that makes me go, this is not a world-class city”. He remembers a time when it was, but it’s not when you might think.

At home, in the leafy western suburb of The Gap, he has a copy of a colour photograph of Brisbane’s main drag, Queen Street, from the late 50s. Historians would have you believe that back then Brisbane was just a big country town.

The photograph tells him it was all that and more. “It looks incredible, like the most gorgeous city you’ve ever seen. It was abeautifulcountry town! It’s all neon; it looks like a cross between Las Vegas and Memphis.”

And now? “It’s been mall-ised, it’s been nibbled away, it’s been destroyed.” (The Queen Street Mall is right behind us.) “It’s luxury. It’s Gucci and Chanel and Louis Vuitton. I’m happy that’s available, but it’s not for me.”

In the Pretenders’ songMy City Was Gone, singer Chrissie Hynde goes back to her home town of Akron, Ohio, only to find that all the things that once bound her to her birthplace have disappeared.

The Go-Betweens’ most famous song is Streets of Your Town, which (depending on who you ask) may or may not be about Brisbane. In the song’s bridge, the late Grant McLennan sings wistfully:“They shut it down, they closed it down, they pulled it down …”

We finish our coffee and head out into a city we barely recognise.

IT’S been a busy year for Forster. His ninth solo album, Strawberries, has just been released. Coming after The Candle and the Flame – which addressed in intimate detail thechallenges faced by his wife’s ovarian cancer– it’s expansive, good-humoured and lush (Bäumler’s cancer is in remission). It might even be his best.

It follows the third and final Go-Betweens box set, a project that took a decade to complete. There’s also a novel, which he’s been working on for nearly as long.

I tease him that it must be approaching Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past by now. He laughs. “No! I don’t want that. I always wanted to write a book of 60,000 words, not 500 pages of me eating a biscuit when I was three years old.” He promises it’s “very close” to completion.

Forster rarely comes into the city any more. “I don’t look for stuff here. I’m in the suburbs, and happy.” Brisbane, he says, is all about pockets – niches that outsiders don’t know about, or bother with. “People find their place in the suburbs and just live in that ecosystem.”

Which begs the question: why meet here? Well, it’s another kind of remembrance of things past; of a town that no longer exists. Brisbane is transforming before our eyes. In 2032, it will host the Olympic Games.

In 1978, the Go-Betweens released their first single,Lee Remick. It begins with a self-deprecating couplet: “She comes from Ireland, she’s very beautiful / I come from Brisbane, and I’m quite plain.” Original copies now change hands for thousands of dollars.

“I wasn’t born in Paris or Rome, I knew that early on,” Forster says. But in many ways, Brisbane was more lively back then than it is now. It was, he says, all about the dimly-lit arcades, “where things were tucked away, out of the relentless sunshine”.

We pause at the top of the Elizabeth Arcade, once a bohemian oasis. Forster remembers it housing an import record store, a vegetarian restaurant, even a communist bookshop: “The Communist party had a bookshop right here at the start of the arcade!”

At the time, the state of Queensland was ruled by Joh Bjelke-Petersen. Forsteronce wrotethat the so-called “Hillbilly Dictator” was “the kind of crypto-fascist, bird-brained conservative that every punk lead singer in the world could only dream of railing against”.

By way of response, Brisbane produced both pioneering punk band the Saints and the Go-Betweens, one of the first post-punk groups. Both would quickly decamp for London. Australia (let alone Brisbane) was not ready for them.

We proceed down Elizabeth Arcade. I ask Forster what he sees. “Progress! I can’t expect everything to be like 1975. I’ve lost the anarchist bookshop, but I’ve got lots of ramen places. Before it was just chops and potatoes and peas.”

We emerge into Charlotte Street. To our right is Archives (est. 1986), a dark, labyrinthine second-hand bookshop, and thePancake Manor(est. 1979), open 24 hours. On our left is Festival Towers, a ghastly apartment block built on top of the old Festival Hall.

This is the last of the old Brisbane that Forster still feels like he knows. He looks up at the Pancake Manor’s old red art-deco brickwork. “I don’t drop to my knees in nostalgia, but I just like that it still exists. This is what I’d keep.”

IN 1989, the Go-Betweens played a celebrated show at Festival Hall, supporting REM. The latter were touring their hit album, Green, and were on the escalator to superstardom. The Go-Betweens had just released 16 Lovers Lane, their final album before the band split.

REM were fans, and understood the significance of the Go-Betweens’ homecoming, playing to a crowd of close to 4,000 people. Forster was setting foot on the same stage where he’d first seen his heroes perform: Roxy Music, Bob Dylan, Talking Heads all played there.

After the show, about 10.30pm, a very Brisbane thing happened. REM were staying at Lennons, on Queen Street. All nine members of the two bands walked from the venue up Albert Street back towards Queen – completely unmolested, unrecognised and undisturbed.

“There was just nothing going on,” Forster remembers. “I’m walking up there with [Peter] Buck and [Michael] Stipe and they’re like, ‘Does anything ever happen here?!’ So that’s a nice memory.”

The day before the show, Rocking Horse Records (est. 1975) would be the subject of a police raid for selling allegedly obscene records. Proprietor Warwick Vere, who still owns the shop, was eventually acquitted.

Brisbane was on the cusp of change. It had been a long time coming. A few months after the raid, the devastatingFitzgerald reportinto police corruption was handed down. Bjelke-Petersen, by then, was gone.

Rocking Horse is another surviving relic of the old Brisbane. The store is now on Albert Street–so naturally, we follow the path Forster, Stipe and company once cut, up towards the shop.

“Grant and I used to come here when it opened. Again, you were in an arcade, so you felt protected – for the 80 metres of that arcade, you weren’t in Brisbane. You might as well have been in Vienna.”

In 1999, McLennan and Forster reconvened the Go-Betweens with a new lineup, making three more albums. The group ended with McLennan’s sudden, shocking death from a heart attack in 2006. He was just 48.

The 20th anniversary of McLennan’s death looms, and I ask Forster how it sits with him. “I miss him more as a friend,” he says. “Karin and I were talking about it, wondering how he would have negotiated those 19 years. What would he have been like?”

Forster is now 67. He’s been through his own health scare, being diagnosed with hep C in 1997. He hasn’t had a drink since, and has long been clear of the disease, but he knows he’s lucky. Many of his peers have been less fortunate.

“I’m 67, but I may as well be 47,” he says. “I find a little bit of wisdom comes with age. Like, you don’t turn into the Dalai Lama, but you improve as a person, I think, as you get older. I think that’s a fact.”

On the wall at Rocking Horse, behind the counter, there’s a copy of the Go-Betweens’ second single,People Say, released in 1979. It’s in its original bright yellow sunflower sleeve and is selling for the princely sum of $650. Forster looks up at it with glee and smiles.

“Absolute bargain,” he declares.

Robert Forster’s ninth studio album, Strawberries, is out now