My earliest reading memoryMy mother reading Kenneth Grahame’sThe Wind in the Willowsto me – and reading it again and again, because I loved it and her. I was perhaps three. We lived in a little mining town in the middle of the rainforest. It was always raining and the rain drummed on the tin roof. To this day that’s the sound I long to hear when I relax into a book – a voice in the stormy dark reminding me that I am not alone.

My favourite book growing upBooks were an odyssey in which I lost and found myself, with new favourites being constantly supplanted by fresh astonishments. Rather than a favourite book I had a favourite place: the local public library. I enjoyed an inestimable amount of trash, beginning with comics and slowly venturing out into penny dreadful westerns and bad science fiction and on to the wonderfully lurid pulp of Harold Robbins, Henri Charrière, Alistair MacLean and Jackie Collins, erratically veering towards the beckoning mysteries of the adult world.

The book that changed me as a teenagerAlbert Camus’s The Outsider. It didn’t offer a Damascene revelation, though. I was 11. I absorbed it like you might absorb an unexploded cluster bomb.

The writer who changed my mindWhen I was 27, working as a doorman for the local council, counting exhibition attenders, I read in ever more fevered snatches Kafka’s Metamorphosis, which I had to keep hidden beneath the table where I sat, balanced on my knees. A close family forsaking their son because he has turned into a giant cockroach, after the death of which they marvel at their daughter’s vitality and looks? It dawned on me that writing could do anything and if it didn’t try it was worth nothing. Beneath that paperback was a notebook with the beginnings of my first novel. I crossed it out and began again.

The book that made me want to be a writerNo book, but one writer suggested it might be possible for me – so far from anywhere – that I perhaps too could be a writer. And that wasWilliam Faulkner. He seemed, well, Tasmanian. I later discovered that in Latin America he seemed Latin American and in Africa, African. He is also French. Yet he never left nor forsook his benighted home of Oxford, Mississippi, but instead made it his subject. Some years ago I was made an honorary citizen of Faulkner’s home town. I felt I had come home.

The book or author I came back toWhen I was young, Thomas Bernhard seemed an astringent, even unpleasant taste. But perhaps his throatless laughter, his instinctive revulsion when confronted with power and his incantatory rage speak to our times.

The book I rereadMost years, Bohumil Hrabal’s Too Loud A Solitude, humane and deeply funny; and Anna Karenina, every decade or so, over the passage of which time I discover mad count Lev has again written an entirely different and even more astounding novel than the one I read last time.

The book I could never read againOn being asked to talk in Italy on my favourite comic novel I reread Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop. It had corked badly. My fundamental disappointment was with myself, as if I had just lost an arm or a leg, and if I simply looked around it would turn back up. It didn’t.

The book I discovered later in lifeGreat stylists rarely write great novels. Marguerite Duras, for me a recent revelation, was an exception. For her, style and story were indivisible. Her best books are fierce, sensual, direct – and yet finally mysterious. I have also just read all of Carys Davies’s marvellous novels, which deserve a much larger readership.

The book I am currently readingKonstantin Paustovsky’s memoir The Story of a Life, in which the author meets a poor but happy man in the starving Moscow of 1918 who has a small garden. “There are all sorts of ways to live. You can fight for freedom, you can try to remake humanity or you can grow tomatoes.” God gets Genesis. History gets Lenin. Literature gets the tomato-growers.

Sign up toInside Saturday

The only way to get a look behind the scenes of the Saturday magazine. Sign up to get the inside story from our top writers as well as all the must-read articles and columns, delivered to your inbox every weekend.

after newsletter promotion

My comfort readOf late, in our age of dire portents, I have been returning to the mischievous joy of James Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson: “There is nothing worth the wear of winning, but the laughter and love of friends.”

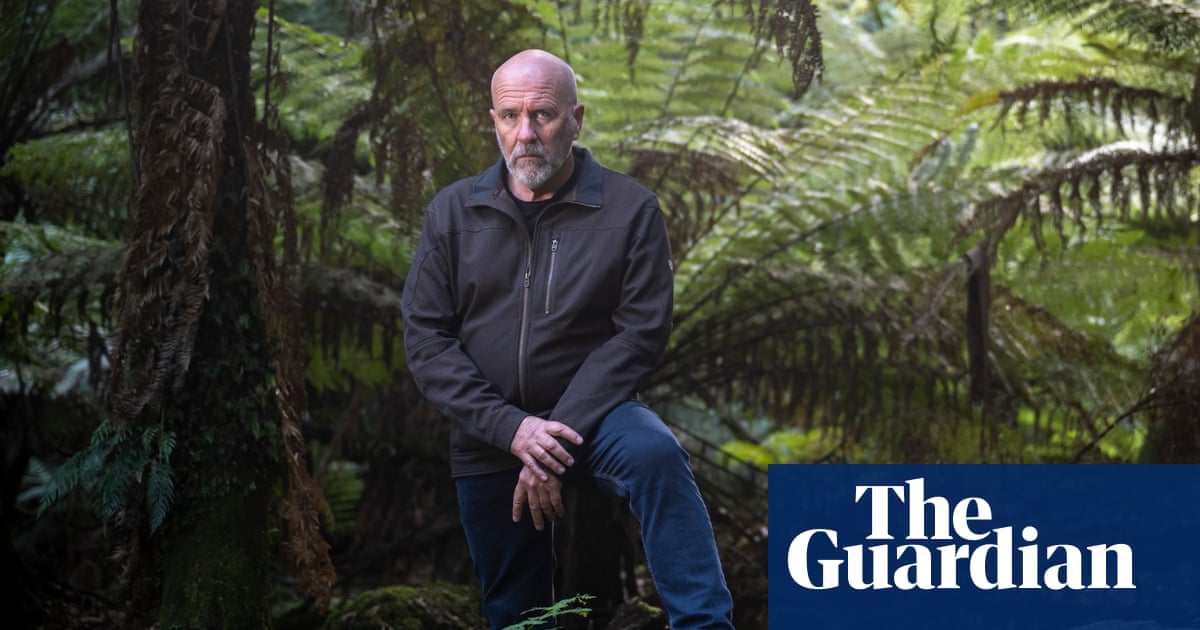

Question 7 by Richard Flanagan is published in paperback by Vintage. To support the Guardian, order your copy atguardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.