In 1976, Richard Appignanesi, who has died aged 84, translated and published Marx for Beginners by the Mexican cartoonist, Ruis. It was the first title to make a real mark for the Writers and Readers Cooperative’s series For Beginners, comic books on great thinkers and big topics aimed at readers of all backgrounds. Appignanesi produced enduring titles in collaboration with his close friend the illustratorOscar Zarate. Freud for Beginners (1979), translated into 24 languages, has been a bestseller for more than four decades.

Appignanesi was a master of the graphic novel – the term was coined by the comic book historian Richard Kyle in 1964, and the genre was a relative innovation in the UK.

He was hands-on, marrying text and image, editing and storyboarding. Writing to the art criticJohn Berger, he claimed that he was the only writer member who “dirtied his hands” on the shop floor. In 1980 his work brought him a Directors Club (New York) merit award for art direction.

After the cooperative broke up in 1984, he co-founded Icon Books, which expanded the series under a new name, Introducing ..., with more than 100 titles. His standalone contributions include Lenin, existentialism and postmodernism.Introducing Postmodernism(2004) is a rollercoaster – taking in Marilyn Monroe, Disney World, The Satanic Verses and cyberspace – the labyrinthine subject illuminated with wit and cartoons by Chris Garratt, cartoonist ofthe Guardian’s strip Biff(1985-2005).

Appignanesi became series editor ofManga Shakespeare(2007-11), adapting Shakespeare plays illustrated by UK Manga artists, the text abridged but unaltered. The 14 titles are still much appreciated by teachers and fly off library shelves.

Emma Hayley of the series’ publisher, SelfMadeHero, remembered his wicked humour: King Lear was illustrated byIlya, known for publications for Marvel, with Lear as the Last of the Mohicans. Hayley also worked with Appignanesi on the Graphic Freud series:The Wolf Man(2012) and Hysteria (2014), exploring Freud’s famous early case studies of psychological disorders through visual storytelling. Introducing The Wolf Man, Appignanesi was circumspect: “It remains for me an open question whether there is such a thing as a cure. Psychoanalysis seems to me a life commitment – like writing.”

He was a pioneer in a field now widely thought by educationists to develop critical thinking, opening the way to deeper reading. His two series for beginners added wry observation to the narrative, raising questions as much as answers. Introducing Lenin and the Russian Revolution (1977), at 175 pages, gives the complexities of the revolutionary movement and Lenin’s rise, but leaves it open whether he was responsible for Stalinism.

Hysteria takes a clearer position on Freud. It is a mordant tale of medical hubris, with Freud’s theories and his doubts and reflections on the errors of his mentor, Jean-Martin Charcot, set alongside the contemporary crisis of mental health and treatment with drug therapies.

Appignanesi’s fiction trilogy Italia Perversa – Stalin’s Orphans, The Mosque and Destroying America (1985-86) – is a dense epic about the relentless European wanderings of a Stalinist Quebec revolutionary who turns terrorist. His novel Yukio Mishima’s Report to the Emperor (2002) received a dressing-down for biographical inaccuracy about the ultranationalist writer whose attempted coup ended in his ritual suicide in 1970. But one online reviewer found it: “a very enjoyable ride. It’s one-part Mishima biography to two parts Mishima’s own fiction to three parts Appignanesi madness.”

His humour, internationalism and literary bandwidth were a pleasure and a support for me when, from 1993, I was working at Arts Council England and had to navigate divisive issues in the visual arts. He was editor ofThird Text, the leading journal of art in a global context, founded by the artistRasheed Araeen, and for Arts Council England compiledBeyond Cultural Diversity(2010). When it was published the following year, Third Text described it as “a timely and uncompromising investigation of what has gone wrong, and why, with state-sponsored cultural diversity policy in Britain”.

He was one of the co-curators for the ICA, London, on Winds of Change: Cinema in Muslim Societies (2011), a programme of film screenings and talks prompted by the uprisings of the time known as the Arab spring, and was a contributor to Critical Muslim, the journal founded by his friend and collaborator Ziauddin Sardar.

Born in Montreal, Canada, Richard was the eldest son of working-class Italian immigrants. His father, Ezio Appignanesi was a talented saxophonist and drove taxis. His mother, Angelina (nee Canestrari) was an amateur actor, seamstress and a great storyteller.

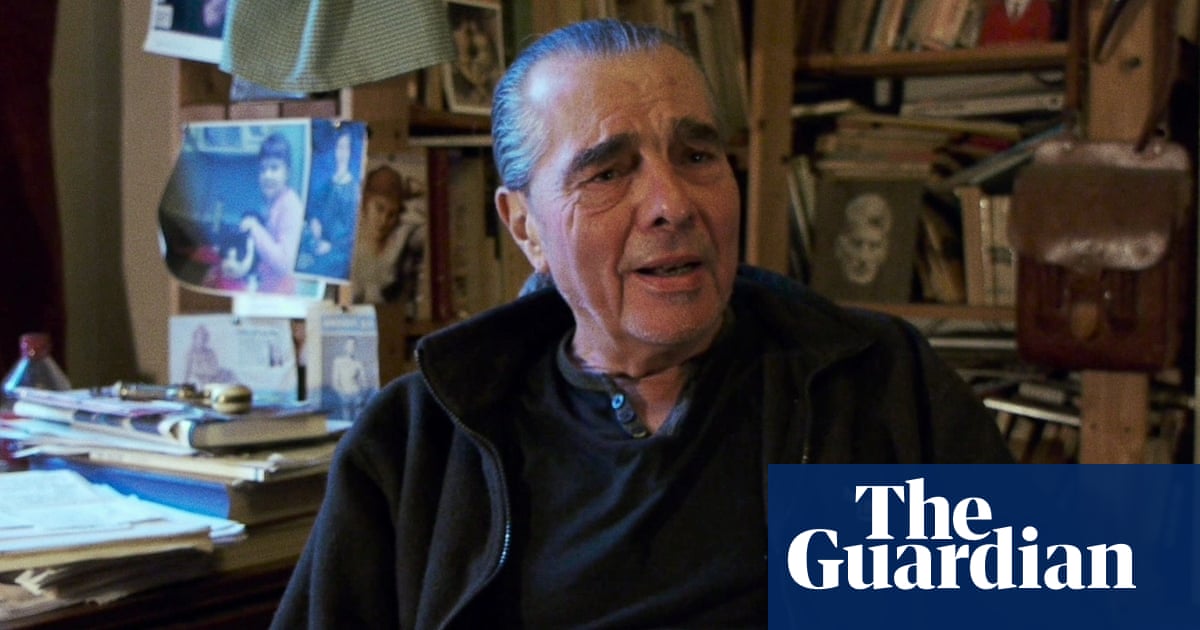

Possessed of Italian good looks and a ponytail, he referred affectionately to his family as “the mob”. Though he won a music scholarship to the Montreal Conservatoire, he gave up the piano when he heardGlenn Gould, the great Canadian exponent of Bach.

After he was suspended from university at 16, his mother sent him to the Jesuit Loyola College, where, “a jazz loving existentialist under the benign tutelage of the Brothers”, he graduated with a degree in English literature in 1962. After being given a large studio, he took up painting, producing big expressionist canvases, not unlike stained glass.

In 1967 he married the writer Lisa Borensztejn,the daughter of Polish parents from Paris. Lisa wanted to do a doctorate in Britain, at Sussex University, and Richard followed, gaining a PhD in art history (1973). During those years they lived in Vienna and Paris. Once they were back in Britain, settling in London, Lisa wrote about a Munich-based bookshop collective. In 1974 this spurred the American publisher and activistGlenn Thompsonto found the Writers and Readers Cooperative with his wife Sian Williams, the Appignanesis, Berger, the playwrightArnold Weskerand the writer Chris Searle. Among their first publications were works by the educationistsIvan Illichand Paulo Freire.

Richard’s maverick versatility drew him to the early 20th-century Portuguese writerFernando Pessoa, whose more than 70 imaginary identities, termed heteronyms, inspired the contemporary art exhibition that Appignanesi curated in 1995 in collaboration with the writer Juliet Steyn. The show toured to Rome with Appiganesi’s play Fernando Pessoa: The Man Who Never Was. He also collaborated with Open Space Vienna, and a version of the resulting exhibition,Raising Dust, was shown in London (2010-11). A central feature in the multimedia show wasthe broom, an emblem of basic human endurance in predominantly eastern European artists’ meditations on waste and the geopolitical irregularities of the continent. In 2005 he co-curated the British Council’s Writing Europe Conference in the Ukrainian capital of Kyiv.

He and Lisa had a son, Josh, and divorced in 1984. In 2014 he married Helen Askey, and they had a son, Raphael. He also had a daughter, Rosa, with Juliet Steyn.

He is survived by his wife, his three children, and his brother Augusto.

Richard Appignanesi, writer, born 20 December 1940; died 8 April 2025