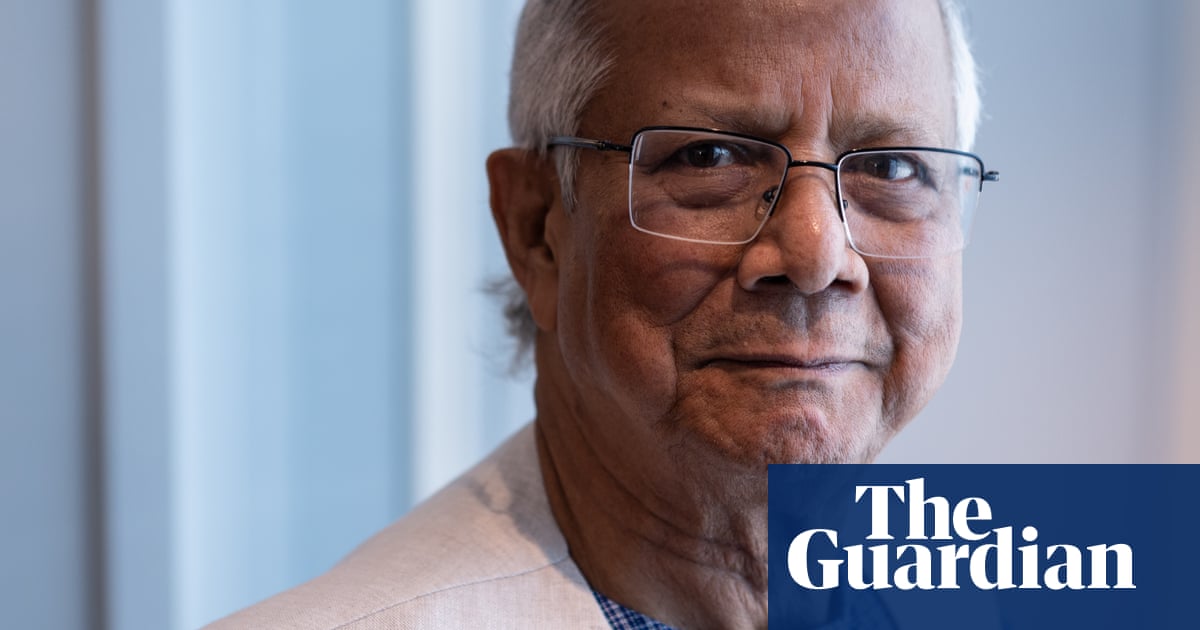

A year on from the political uprising that swept the prime minister ofBangladeshinto exile, people still see government as the enemy, according to the country’s interim leader, Muhammad Yunus.

Rooting out corruption at every level, from village to government, is the only way for people to believe in a “new Bangladesh”, he says.

TheNobel Peace prize winner, who took over after July’s student-led revolt unseatedSheikh Hasina, told the Guardian he wants the state to deliver more for citizens who have felt the government offers them little.

Pervasive corruption has included the siphoning off of money by government members and demands for bribes in every transaction from getting a passport to applying for a business permit, he says.

“Somebody is [always] waiting to grab an enormous amount of money,” says Yunus. “People see government as your permanent enemy and you have to live your life fighting with this enemy. It’s a very powerful enemy, so you want to stay away.”

While the protests were prompted bystudent anger over a quota systemfor government jobs that favoured the then ruling Awami League party’s allies, there was also discontent over high living costs and a lack of opportunities for young people.

Hasina had become increasingly authoritarian, cracking down on the opposition and freedom of expression, while the breakdown of the banking systemhas been attributedto corruption among the elites.

Many hoped the protests in the summer of 2024 would lead to radical changes to a toxic, confrontational political system dominated by two rivals – the Awami League and the Bangladesh Nationalist party (BNP).

“Our starting point was a devastated economy, a devastated society. Administration had totally collapsed,” says Yunus. “We didn’t even know whether we could pay our bills. Massive amounts of financial resources were just siphoned up as if they didn’t belong to anybody – just taken. Banks issued loans, knowing full well that these were not loans, just gifts [that were not paid back].”

A series of reform commissions formed by the interim government made recommendations in January covering elections, corruption and welfare. Yunus is now focused on forging an agreement on these reforms between the country’s political parties, and wants the so-called July Charter to be finished before the first anniversary of the protests next month, so that they can focus on implementing them ahead of an April election.

“It will be a historical document, to bring all these people together. The recommendations of the commissions are fundamental recommendations, not light things, not just to do a little better, a little of this or that – no,” he says. “Then our job is to implement and prepare the country, moving towards a sane, functioning system.

“Afterwards, we can feel happy that we are in a situation to make a beginning of the new Bangladesh.”

Yunus admits, however, that agreement will not be easy.

The BNP, now the country’s most powerful party and the clear favourite to win an election, has been pushing for an earlier poll date and has opposed the proposed two-term limit for prime ministers.

Sign up toGlobal Dispatch

Get a different world view with a roundup of the best news, features and pictures, curated by our global development team

after newsletter promotion

But Yunus says he is encouraged by how the parties have engaged with each other so far, in a country where there was little precedent of consensus between opposing politicians.

Yunus wants to change how the state functions and serves the people, for example encouraging nonprofit social businesses that could deliver on issues such as healthcare, and expanding on the microcredit model he pioneered.

The sector is now dominated by NGOs that provide small loans to people living in poverty to allow them to start businesses. Yunus wants to formalise that systemby creating dedicated microfinance banks.

He says this would encourage entrepreneurship, as people would not have to rely on traditional banks, which often refuse to lend to poor people.

Microcredit has gained a bad reputation, he believes, in part due to some lenders pushing high interest rates, but he says the model had been exported and copied globally.

“[People think] it’s extracting money out of the poor people but that’s not what it does. So it was given a bad name and then people said, ‘Oh, you have to improve it.’ You don’t have to improve it … there is nothing wrong with microcredit,” he says.

Yunus has been critical of the mainstream banking system, which poorer people without assets can often not access but which has also crumbled in the past year after the non-payment of large loans taken by allies of Hasina, leading at times to citizens being unable to withdraw their money.

Just a year ago, Yunus was publicly vilified by Hasina, before being suddenly thrust into government. He says he does not plan to stay on in government after the election in April, but until then will focus on trying to balance the many political pressures while trying to implement the reform mandate.

“Before, I was criticised by the Awami League and its leaders, now everybody criticises me – it’s open game. This is part of life if you’re holding this position, people will have their opinions. You have to go through it and accept it,” says Yunus. “[In April] we will have an elected government and then we’ll disappear.”