During last week’s tense debate over whether thePakistansenate should pass a bill banning child marriage, Naseema Ehsan stood up to speak. “I got married at 13 years old and I want child marriage to be banned,” said the 50-year-old senator.

“I was lucky to have good and affluent in-laws but most Pakistani women are not so lucky. Not every child has a supportive husband like me.”

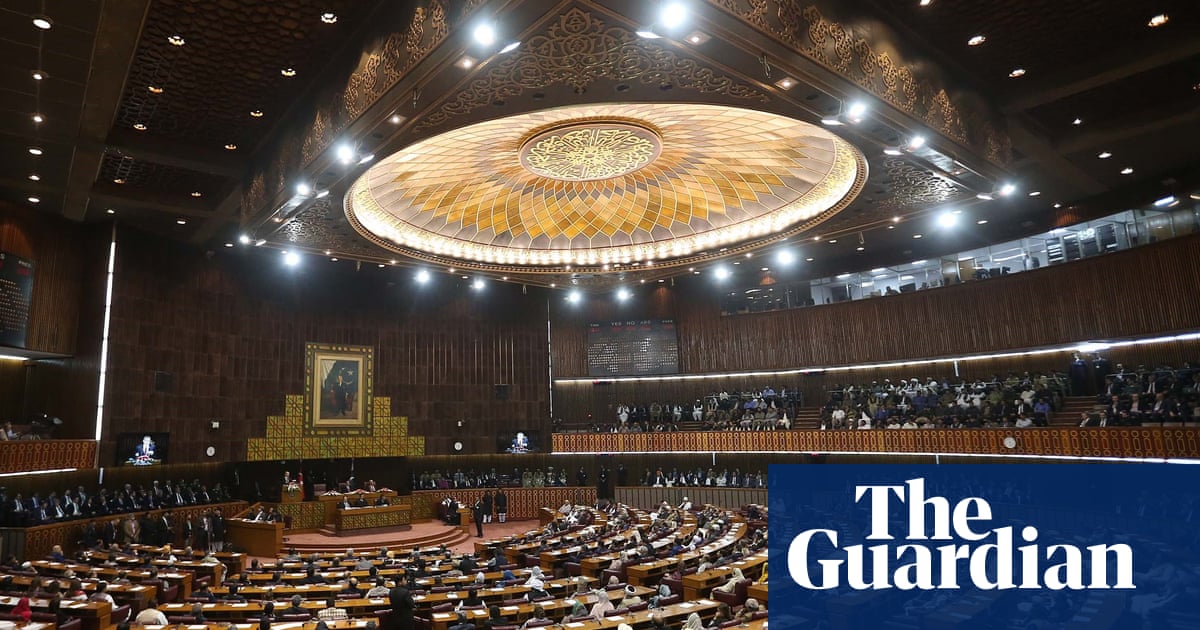

When she finished talking, there was applause in the chamber.

Despite fierce opposition, later that day thebill banning child marriage in Pakistan’s capital city, Islamabad, was passed. It will be signed into law by the president in the coming days and replace legislation introduced under British colonial rule.

The landmark parliamentary vote comes more than a decade after a similar bill was passed in Sindh province. Senators, civil society organisations and activists hope that because this latest bill was passed by both houses of Pakistan’s legislature, other regions will follow suit, eventually outlawing child marriage throughout the country.

“This bill sends a powerful message,” saysSherry Rehman, the politician who tabled the bill in the senate after Sharmila Farooqi introduced it in Pakistan’s lower house, the national assembly.

“It’s a very important signal to the country, to our development partners, and to women that their rights are protected at the top.”

Under the new legislation, the minimum age for marriage is 18 for both males and females in the capital, with underage marriage now a criminal offence. Previously, it was 16 for girls but 18 for boys.

Strict punishments, including up to seven years in prison, have been introduced for people – including family members, clerics and registrars – who facilitate or coerce children into early marriage.

Any sexual relations within a marriage involving a minor – with or without consent – will be deemed statutory rape, while an adult man found to have married a girl could face up to three years in prison.

It is a moment of hope in an increasingly gloomy landscape for women’s rights globally, according to Jamshed Kazi, Pakistan’s representative for UNWomen.

“This particular passage [of the bill] is even more significant because it’s happening in the wake of counter-currents,” he says.

“We are seeing a global pushback on women’s rights and even a renegotiation of issues that were settled maybe 30 years ago. Countries are challenging the use of gender-responsive language, and even sexual and reproductive health and rights.”

In Pakistan,29% of girls are married by 18,according to a 2018 demographic survey,and that4% marry before the age of 15compared with 5% for boys, according toGirls Not Brides, a global coalition aiming to end child marriage. The country is among the top 10 worldwide with thehighest absolute numberof women who were married or in a union before the age of 18.

Girls who marry areless likely to finish schooland are more likely to face domestic violence, abuse and health problems. Pregnancies become higher risk for child brides, with a greater chance of fistulas, sexually transmitted infections or even death. Teenagers are more likely to die from complications during childbirth than women in their 20s.

Ehsan knows only too well the dangers facing girls who are married early. She had her first child at 15. “I had complications during pregnancy,” she told the Guardian.

“Doctors told me I was weak because I was very young – a child. My health, and my daughter’s health, were affected,” she says.

Her in-laws could afford medical care and she had three more children in consecutive years. She dropped out of school but her husband allowed her to continue her studies privately.

“At 20, I came to the realisation that I should have finished my studies and waited till 19, at least, to become a mother. I would have been able to take care of my children more,” she says.

Since then, she has seen many cases of child brides dying in childbirth in her home province of Balochistan, where girls can get married at 16. A woman dies due to pregnancy complications in Pakistanevery 50 minutes.

“I’ve never been so content to vote for a bill as the child marriage restraint bill,” she adds. “The world has changed and developed. We have progressed and we must embrace the progress … It was a very much needed bill.”

It has been “a long time coming”, according to Kazi, and is the result of more than a decade of advocacy by civil society and rights organisations.

Rehman says it follows three attempts over seven years to get a ban passed, with previous bills falling victim to parliamentary inertia as well as religious opposition.

“It has been difficult to go through various stages and jump through hoops, and to keep making amendments,” she adds.

“To see it defeated repeatedly, or not even make the agenda because there was opposition in the National Assembly, has been one of the most difficult parts of this journey.”

Some religious and political leaders have threatened to protest against the bill, claiming it is “unIslamic”, that marriage must be a family decision and that puberty should mark the age a girl can be married.

“We should not be forcing the age of child marriage. Parents should decide that and children should consent to it,” says Maulana Abdul Ghafoor Haideri, secretary general of the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam Fazl political party.

“In Britain and western societies, during adulthood they have relations and partners, and they have sex and then do abortion and waste their children. Why don’t Pakistani liberals and civil society and even the west see that and introduce laws over there?

“This new law is unacceptable and unbearable,” he says. “We will decide our course of action.”

Nadeem Afzal Chan, information secretary of the Pakistan People’s party – which is in power in Sindh and Balochistan provinces – refutes such claims.

“We must celebrate this bill as it protects the rights of children,” he says. “The Balochistan government soon will enact laws to ban child marriages.”