Breathless, deathless … and pointless? Here is Richard Linklater’s impeccably submissive, tastefully cinephile period drama about the making of Godard’s debut 1960 classic À Bout de Souffle, that starred Jean Seberg and Jean-Paul Belmondo as the star-crossed lovers in Paris. Linklater’s homage has credits in French and is beautifully shot in monochrome, as opposed to the boring old colour of real life in which the events were actually happening; he even cutely fabricates cue marks in the corner of the screen, those things that once told projectionists when to changeover the reels. But Linklater smoothly avoids any disruptive jump-cuts.

It’s a good natured, intelligent effort for which Godard himself, were he still alive, would undoubtedly have ripped Linklater a new one. (WhenMichel Hazanavicius made Redoubtable in 2017about Godard’s making of his 1967 film La Chinoise, the man himself called that “a stupid, stupid idea”; Hazanavicius wasn’t even making a film about Godard’s first and biggest hit.

Yet Linklater is of course unconsciously creating a stylistic homage – not to Godard, however, but to his much more emollient, accessible and Hollywood-friendly collaborator Francois Truffaut. Truffaut wrote the basic story for Breathless and thereby gave Godard his commercial success; it was based on a sensational true-crime story about a tough guy who shoots a cop and gets an American girlfriend on the run, grabbing at love and romance while he can, existentially aware that a cop-killer’s days are numbered.

The real-life characters of the Breathless story, from the most famous to the most obscure (this latter category being of course treated with rigorous superfan respect) are introduced with static portrait shots, gazing at the camera with their names flashed up on screen; even in the action itself, these people are often addressed by their full name with an awestruck sentence about their importance so we know where we are.

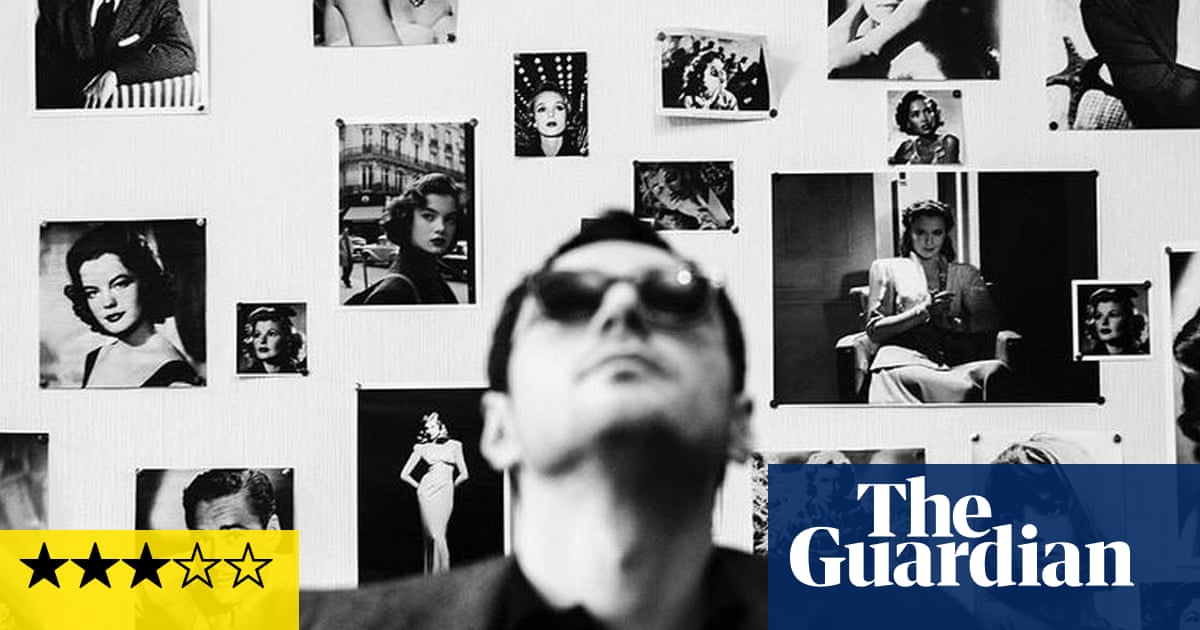

Godard himself, a Cahiers Du Cinéma gunslinger-critic yearning to graduate to film-making, is played by newcomer Guillaume Marbeck, incessantly dropping epigrams and wisecracks and shruggingly dismissive pouts on the subject of cinema – and perhaps Godard was like this, at least some of the time. Linklater mischievously allows the audience to wonder if Godard will ever remove his sunglasses and get a “beautiful librarian” moment, or at least a moment to confess that you shouldn’t watch movies through dark glasses. Aubry Dillon plays Belmondo and Zoey Deutch is Seberg, forever breaking into fluent and Ohio-accented French. Adrien Rouyard is Truffaut, Matthieu Penchinat is the brilliant cinematographer Raoul Coutard whose news background in covering wars made him an inspired choice for Godard’s guerrilla film-making adventures, Benjamin Clery is Godard’s first assistant director Pierre Rissient and Bruno Dreyfürst is Godard’s long-suffering producer George “Beau Beau” Beauregard - whose disagreements with Godard over money lead to an undignified physical scuffle in aPariscafe.

The shoot begins, extended by Godard’s haughtily capricious delays to accommodate authentic inspiration, as the actors amusingly say whatever they like to each other and the tyrannical director while the camera is turning, because everything is to be dubbed later in the studio. Continuity supervisor Suzon Faye (Pauline Belle) crossly tells Godard that his cavalier disregard for matching the eyelines in successive shots mean a problem in the edit; a hint of the imminent revolution in film grammar, perhaps, though Linklater’s Godard has the humility to say he didn’t invent jump-cuts.

By the end, Linklater’s Godard is as opaque and essentially imperturbable as he was in the beginning, seething with competitive anguish at the success of Truffaut’s The 400 Blows in Cannes and struggling to get into parties and film sets; and again, none of this, arguably, is inaccurate. But it’s all very smooth: a slick Steadicam ride through a historic, tumultuous moment.

Nouvelle Vague screened at theCannes film festival.