In the opening scene of Time Flower, a surrealist film by the zoologistDesmond Morris, a woman is lying facedown on the ground, clutching the grass with manicured hands and shaking her head. She is about to start running across a Wiltshire moor in elegant black heels, chased by Morris in a shirt and tie, her eyes wide, her lipstick dark, the angle of the shot emphasising her perfect, parted, panting mouth. Just before she trips and falls, a wild rabbit will stare straight at the camera – and flee.

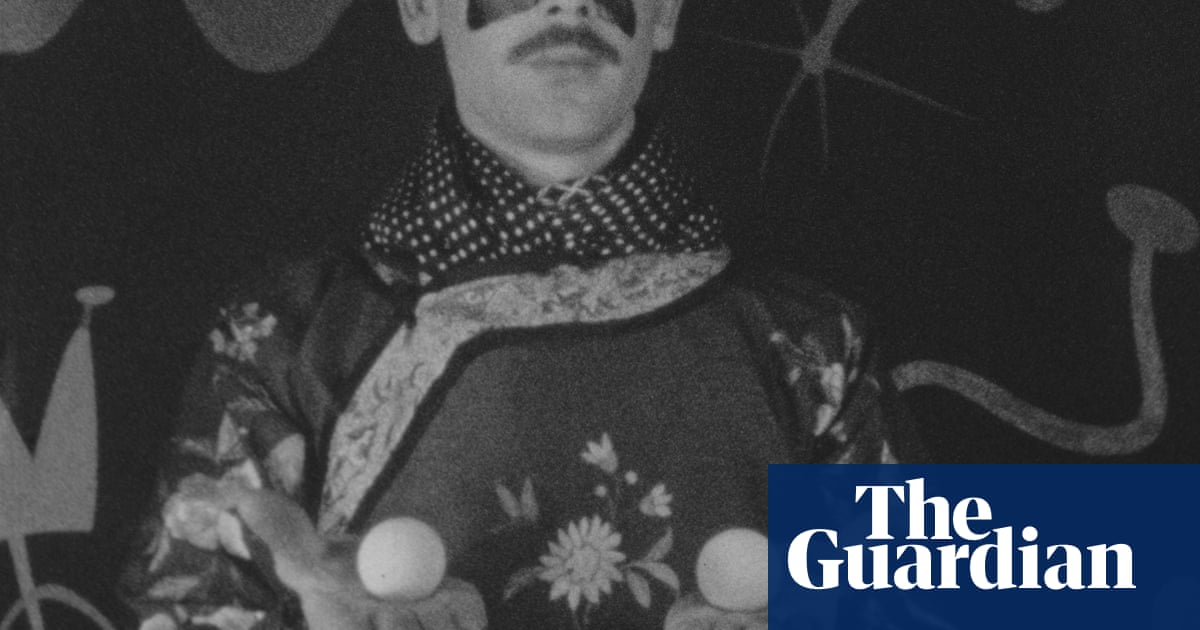

This 10-minute black-and-white film, which Morris made in 1950 while he was a 22-year-old student at Birmingham University, has lain untouched in his archive for nearly 75 years. Created in response to Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel’sUn Chien Andalou, it is a testament to Morris’s early work as a surrealist artist. He exhibited alongside Joan Miró before he became a zoology broadcaster and the author ofThe Naked Ape.

Now 97, Morris has decided to allow the film – which stars his late wife Ramona, with whom he co-wrote the 1966 book Men and Pandas – to be shown for the first time since the 1950s, at theUniversity of Birminghamduring the Flatpack film festival. “While I was studying zoology at Birmingham,” says Morris, “I joined a club that showed films – and one of the first was Un Chien Andalou. It shocked, startled and excited me. That was when I decided to make my own surrealist film.”

He had met Ramona playing sardines (a variation of hide-and-seek) at a country house party in the spring of 1949, when she was 18. He fell madly in love, he says, pursuing her all the way to France when she moved there. “My pursuit of Ramona in the film is symbolic of my pursuit of her in real life,” he says. “The film was inspired by the love story of my life. We stayed together as a couple until she died at the age of 88 in 2018.”

He calls Time Flower “a cyclic film in which the end and the beginning are more or less the same. It starts with the man chasing the woman, and he continues to pursue her throughout the whole film until he finally catches up with her – and dies. But the point is that, while he’s chasing her, she has fantasies and he has fantasies, and these are what’s going on in their unconscious minds during the chase.”

He persuaded Ramona to star in it after she returned to England. “In 1950, our relationship was fresh and young: we were falling deeply in love with one another, and it was very passionate,” he says. “But a passionate relationship of that kind isn’t just sexual. It has to be more. And what I really respected, apart from her body, was her brain, which was extraordinary, as were her courage and generosity. She would do anything I asked her to do for the film.”

He decided to propose to her after she agreed, for the film, to leap off the bonnet of his car late at night to catch a wild rabbit frozen in the headlights. “I was joking when I suggested it to her, but she said, ‘Yes of course I will.’ She sat on the front of the car, the rabbit came out, froze, I stopped the car – and she was thrown off on to the rabbit.”

All hell broke loose. “These rabbits were big and it was fierce – scratching and biting her – and so I rushed round with a blanket. We got it home and I kept it in an enclosure until we were ready to film. Then we shot a few seconds before it ran off. But what I discovered that day – and this is one of the big bonuses, for me, of making Time Flower – was my girlfriend’s extraordinary courage. I thought, ‘If somebody’s prepared to be thrown off my car to catch a rabbit for me, then I’ve found the girl I want to marry.’ That was the moment I decided.”

He sees no connection between the animalistic, highly sexualised relationship between the film’s protagonists and his landmark study, The Naked Ape, which suggested human sexual traits and behaviour could only be understood in the context of animal behaviour and evolution. “Apart from the rabbit, there wasn’t much zoology – although a hedgehog appears at one point,” he says. “No, my zoological research was quite separate.”

But he acknowledges that the film and his surrealist paintings, which he continues to create every night between the hours of midnight and 4am, may have been indirectly influenced by his knowledge of natural history and nature, and his lifelong interest in the reproductive behaviour of animals. He still sees humans as “very strange apes” and “the way in which animals perform strange, bizarre courtship dances” has always fascinated him, visually. “It wasn’t a zoological film, but it did have an underlying, implicit eroticism,” he says. “There’s a great deal of sexual implications in the film, if not explications.”

In 1951, Time Flower was given an award by the Institute of Amateur Cinematographers and Morris filmed a sequel, The Butterfly and the Pin. “That one was a complete disaster, I won’t let anyone see it. It’s about an artist being visited by ‘life’ and ‘death’ in his studio, with a man representing death and a woman representing life, and these two characters fight over the artist. It was a good idea, but the lack of funds to finance it affected the production.”

He never made any other films and became too “embarrassed” to let anyone watch Time Flower. “Its production values are appalling and there were so many things I couldn’t film that I wanted to.” But after he was approached by the film-maker Andy Howlett, who had staged a “seance” of Time Flower at a gallery in Birmingham in 2016, he agreed it could be shown during the Flatpack festival as part of the University of Birmingham’s 125th anniversary celebrations this weekend. “I had another look at it – I hadn’t seen it myself for a long time – and I thought, ‘Well, it may be crudely and poorly produced but it has a kind of irrational intensity that I like.”

The film will be screened twice at the festival, first with its original Prokofiev accompaniment and then with a new live score by Kinna Whitehead, before being deposited for posterity with the BFI National Archive. Although he still wishes Time Flower were a better film, Morris is pleased that audiences are interested in his surrealist work and says that demand for his paintings, which are stillregularly exhibited, has also increased in recent years. “I think it’s because they know that when I die, which can’t be very far off, my prices will increase. Because the best career move for any artist is to die, of course. Your work becomes much more valuable.”

One painting he made in 1948 sold for more than £50,000 two years ago. “I was cross because I wanted to buy it myself. It was one of my favourite paintings and I wanted it back.” It has been “lovely”, he says, to remember Ramona as a young woman again in Time Flower, and that is one of the key reasons he wanted the film to be shown. “I’ve outlived her now by more than six years and it’s very strange to still be here, without her, after a relationship that lasted 69 years.”

He is grateful, however, that he is still able to write and paint. When it comes to living a long life, “that’s the secret,” he says. “I don’t know why the hell I’m still here – but that’s what keeps me going.”

Time Flower will be shown on Saturday 10 May atthe Exchangeat 4.45pm as part of the University of Birmingham’s 125th anniversary celebrations andFlatpack festival.