Released smack-dab in the middle of the 70s, like some gravitational mass at the center of the galaxy,Robert Altman’s Nashville is the defining work of a decade when iconoclasts upended Hollywood and took stock of the country during a turbulent stretch.

For Altman, it was the culmination of a film-making style he had been refining since MAS*H in 1970, one built on spontaneity, a rich evocation of time and place, and actors empowered to create characters who seem to simply exist in their worlds, rather than impose themselves on it. The offhand magic ofNashvilleis that it feels modest, despite a who’s who of two dozen stars convening for an epic that offers Music City as a microcosm for America herself. Rarely are great films this casually profound.

Fifty years later, Nashville has pollinated many more ensemble productions that brings their casts together under a large thematic umbrella, including plenty more from Altman, such as A Wedding, The Player, Short Cuts and his swan song, A Prairie Home Companion. But while other films of the era had attempted to work on a similar scale, like Irwin Allen disaster pictures or Stanley Kramer productions, Altman was attempting to reinvent what films could be, which proved a much harder path, even at a time when the auteur lunatics were running the studio asylum. Though Nashville turned out to be the rare Altman hit, it was bankrolled by a record company. Hollywood didn’t have the nerve for Altman’s narrative experiment.

Working from a script by Joan Tewkesbury, who had also written his superb Depression-era crime drama Thieves Like Us the year before, Altman turns Nashville into a slice of life that seems to stumble by accident into a bigger cultural moment. The overlapping dialogue on the soundtrack marks the film as unmistakably his own, and it challenges the audiences to listen in, as if they’re eavesdropping from a nearby table. The effect is an almost documentary-like naturalism, in which characters on their own individual trajectories collide and break apart, leaving a trail of dialogue behind them. Some of that dialogue is hilariously low-key, some barely intelligible, some flashing with insight into this vast constellation of human experience. Altman doesn’t ask the audience to pick up on all of it, just to immerse themselves in his world.

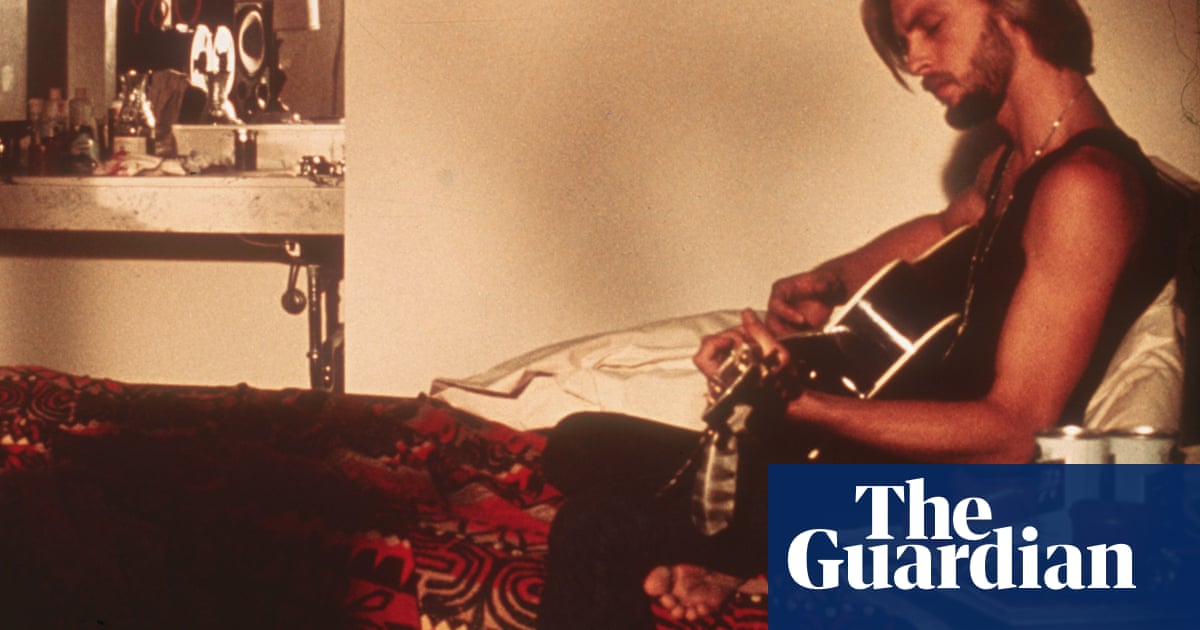

The music alone makes it easy, with several of the actors composing the songs they are asked to sing in the film, like the rival country and western crooners played by Ronee Blakley and Karen Black, and Keith Carradine, who won an Oscar for I’m Easy, a folk song that references the many notches on his character’s bedpost. Though Altman’s perspective on the music industry oscillates between contempt and affection, the sheer variety of performances in Nashville is astounding, starting with an early sequence in which Haven Hamilton (Henry Gibson) is recording a patriotic bicentennial anthem in one studio while Linnea, a white gospel singer (Lily Tomlin), lays down tracks with a Black choir in another. Everyone is so desperate to make it, in fact, that there’s an open mic in the middle of a stock car race.

Other than the stages at Opryland USA, the unifying event in Nashville is a fundraising gala for a third-party candidate named Hal Philip Walker, who never actually appears on screen but whose platform drones through the loudspeakers atop his campaign van. His views are hard to place on the political spectrum, but his grievances make him sound like the uncle everyone dreads having home for Thanksgiving. (“Let’s consider our national anthem. Nobody knows the words … ”) With a US presidential election coming the next year, Walker’s organizers (Ned Beatty and Michael Murphy among them) are trying to wrangle marquee names like Haven and Barbara Jean (Blakley) to perform at the Parthenon, the city’s replica of the Greek temple.

Though the final sequence at the Parthenon brings the film to a shocking yet poignant conclusion, Altman and Tewkesbury stage a journey of constant detours, with a particularly sharp emphasis on the shared dreams of fame and the often humbling road to get there. For women in particular, it’s an ugly minefield of gatekeepers and misogynists, whether it’s Barbara Jean’s temperamental husband/manager (Allen Garfield) micromanaging her affairs, Tom (Carradine) playing seduce-and-destroy, or would-be up-and-comers exposing themselves to open mic crowds. In the film’s most devastating scene, a beautiful waitress (Gwen Welles) with an unfortunate voice gets coerced into turning a singing gig into an impromptu striptease act. Such is the abattoir of celebrity.

Other familiar faces may be limited to minor contributions in Nashville, but they’re all like excerpts from short stories that tease your imagination and make you wonder more about them. Shelley Duvall keeps popping up in a funny role as Martha, a star-obsessed scenester who calls herself “LA Joan” and keeps sidling up to good-looking musicians, despite ostensibly being in town to visit her dying aunt. Geraldine Chaplin ambles around with a recorder, claiming to be a BBC documentarian, but she winds up serving as the film’s de facto guide, with odd diversions like a poetic monologue about the junkyard. Elliott Gould andJulie Christieplay themselves as big-time movie stars, which has the effect of connecting Altman’s fictional milieu with the real world. Who’s to say what’s authentic?

The assassination of JFK and other political leaders over the previous decade haunts the finale of Nashville, which assembles all its characters for a piece of historical destiny. Though it’s Altman’s instinct to be pessimistic about politics and the coarsening soul of the country, the same generous spirit that brought all these characters to life shines through in a chorus that speaks to the best of humanity. The ending is tragic and beautiful, embodying the many Americas refracted through Altman’s lens for over half a century.