WhenEthiopiawas chosen by the United Nations to host the global celebrations for World Press Freedom Day in May 2019, it held a glitzy ceremony in the capital, Addis Ababa, attended by nearly 1,000 people.

The prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, had come to power a year earlier promising to end decades of repression and usher in an unprecedented era of freedom. Exiled news outlets were invited back to Ethiopia, journalists were released from prison and a host of new publications sprang up.

But any hopes of a lasting press freedom were dashed in 2020 with theoutbreak of warbetween Abiy’s military forces and local rulers in Tigray, Ethiopia’s northernmost region. Amid mounting allegations of atrocities, the government restricted journalists’ access to Tigray and imposed a communication blackout, cutting off the region’s phone and internet.

Ethiopia clamped down on independent media, claiming it was protecting national security and describing the rebels in Tigray as terrorists. Initially, the government refused to term the conflict a war and instead referred to it as a “law-enforcement operation”, anticipating a swift victory.

By the time the conflict ended two years later,about 600,000 people had been killedand nearly 10% of women aged 15 to 49 in Tigray had been raped.

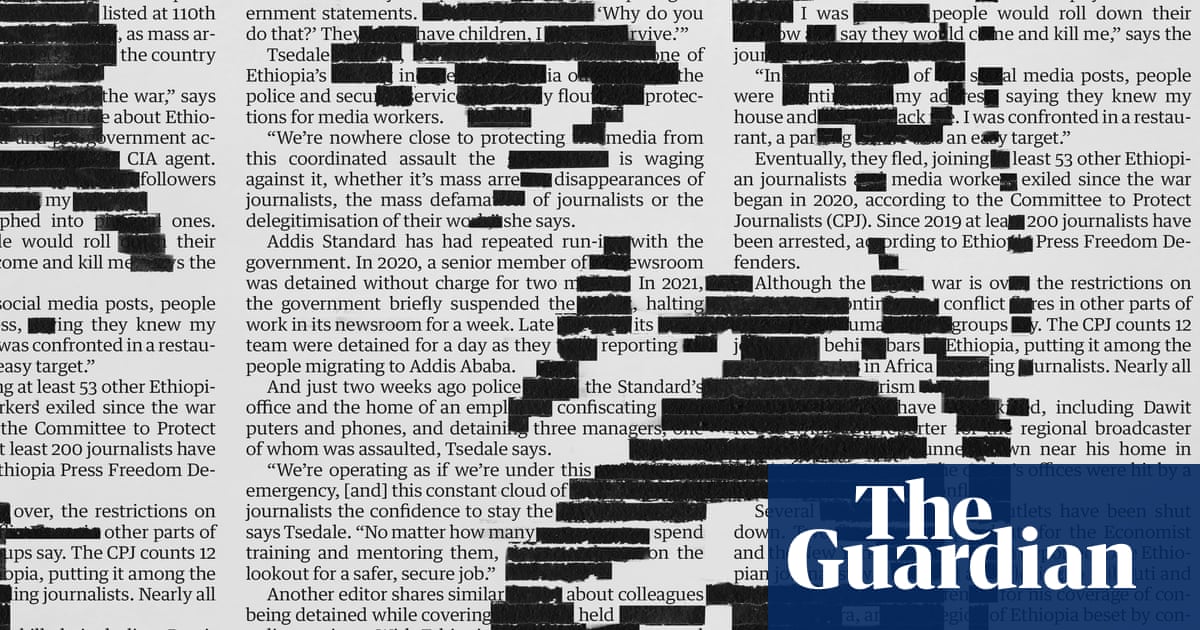

According toReporters Without Borders’ annual press freedom index, Ethiopia went from being 110th out of 180 countries in 2019 to 145th this year, as mass arrests and the detention of media workers across the country took their toll.

“My trouble started on the first day of the war,” says one Ethiopian journalist. “I wrote an article about Ethiopia descending into a civil war and pro-government activists started labelling me a mercenary, a CIA agent.

“These people had hundreds of thousands of followers [on social media] and were sharing my picture.”

Soon, online threats morphed into physical ones. “While I was driving, people would roll down their window and say they would come and kill me,” says the journalist.

“In the comments of the social media posts, people were pointing out my address, saying they knew my house and would attack me. I was confronted in a restaurant, a parking lot … I was an easy target.”

Eventually, they fled, joining at least53 other Ethiopian journalists and media workers exiledsince the war began in 2020, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). Since 2019,at least 200 journalists have been arrested, according to Ethiopia Press Freedom Defenders.

Although the Tigray war is over, the restrictions on media have continued as conflict flares in other parts of the country, human rights groups say. The CPJ counts 12 journalists behind bars in Ethiopia, putting it among the worst countries inAfricafor jailing journalists.

Two journalists have been killed, includingDawit Kebede Araya, a reporter for the regional broadcaster Tigrai TV, who was gunned down by an unidentified attacker near his home in Tigray in January 2021. In 2022, the Dimitsi Woyane TV station in Tigrai was hit by adrone strike. The CPJ did not attribute either to the government, but called for an investigation.

Several independent media outlets have been shut down. Two foreign correspondents for the Economist and the New York Times have been deported. One Ethiopian journalist wasarrested after fleeing to Djiboutiand charged with terrorism offences for his coverage of conflict in Amhara, another region of Ethiopia beset by conflict.

Muthoki Mumo, CPJ’s sub-Saharan Africa representative, says: “Authorities often invoke anti-terror and hate speech laws, as well as state-of-emergency provisions, to suppress critical reporting and to hold journalists behind bars on vague allegations and charges, amid seemingly indefinite investigations.”

Amir Aman Kiyaro, a freelance videographer for the Associated Press,was detained in 2021at his home in Addis Ababa after returning from a trip to Oromia, Ethiopia’s biggest region, to report on a rebel group there. At the time, war was creeping close to Addis Ababa and a state of emergency was in place that curtailed civil liberties.

Amir wasdetained for four months but never charged. State media outlets accused him of colluding with the rebels, who are classed as terrorists.

“As an independent journalist, I wanted to talk to people and document the situation on the ground,” he says. “They were portraying me as having committed a cardinal sin, something very terrible, just for doing my job.”

Last month, policedetained seven journalistsat the privately owned Ethiopian Broadcast Service. On 23 March the outlet had aired claims by a woman who said she had been raped by soldiers in 2020.

The woman later recanted her allegations and the outlet’s founder apologised, saying it has discovered the allegations were fabricated after the programme had aired. Police accused the journalists of terrorism and working with “extremist” groups to overthrow the government.

“If you are not promoting what the government wants, you are seen as against the system,” says an editor. “Every week, we get letters from government offices complaining about our coverage.

“It’s not because we publish wrong facts, but because we are reporting on things like conflict and inflation, things that are seen as critical.”

Most journalists now practise self-censorship, says the editor: “Many independent media just repeat government statements. I ask the journalists, ‘Why do you do that?’ They say, ‘I have children, I need to survive.’”

Tsedale Lemma, founder of Addis Standard, one of Ethiopia’s leading independent media outlets, says the police and security services routinely flout legal protections for media workers.

“We’re nowhere close to protecting the media from this coordinated assault the government is waging against it, whether it’s mass arrests, disappearances of journalists, the mass defamation of journalists or the delegitimisation of their work,” she says.

Addis Standard has had repeated run-ins with the government. In 2020, asenior member of its newsroom was detained without chargefor two months. In 2021, thegovernment briefly suspended the outlet, halting work in its newsroom for a week. Late last year, its video team were detained for a day as they were reporting on people migrating to Addis Ababa.

Justtwo weeks ago police raided the Standard’s officeand the home of an employee, confiscating computers and phones, and detaining three managers, one of whom was assaulted, Tsedale says.

“We’re operating as if we’re under this total state of emergency, [and] this constant cloud of fear doesn’t give journalists the confidence to stay the course with you,” says Tsedale. “No matter how many resources you spend training and mentoring them, they are always on the lookout for a safer, secure job.”

Another editor shares similar stories about colleagues being detained while covering news and held for days at police stations. With Ethiopia gearing up for its general election in 2026, he fears further clampdowns. “In two years, we won’t have any independent media left if things continue like this.”

A government spokesperson did not reply to messages seeking comment on the state of press freedom in Ethiopia.

It has previously said several independent media outlets are highly partisan and do not adhere to proper journalistic ethnics regarding impartiality and verifying facts, instead advocating for certain ethnic groups within Ethiopia’s multi-ethnic federation of more than 80 different peoples.