There are two kinds of readers: those who would choose death before dog-ears, keeping their beloved volumes as pristine as possible, and those whose books bear the marks of a life well read, corners folded in on favourite pages and with snarky or swoony commentary scrawled in the margins. The two rarely combine in one person, and they definitely don’t lend each other books. But a new generation of readers are finding a way to combine both approaches: reviving the art and romance of marginalia, by transforming their books and reading experiences into #aesthetic artifacts.

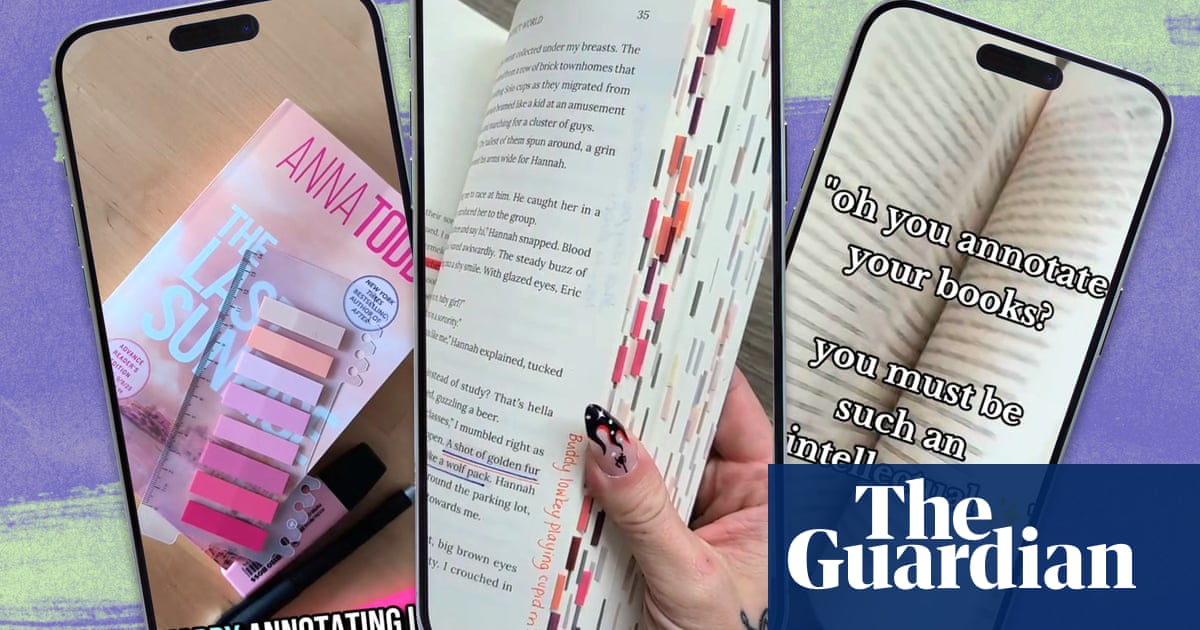

“I keep seeing people who have books like this,”says one TikToker, their head floating over a greenscreened video of fat novels bristling with coloured sticky tabs. “What are you doing? Explain yourselves! Because this looks likehomework. But also … I do like office supplies.”

InBookTokand Bookstagram communities – where social media users post reviews, recommendations and memes about reading – there are subcommunities devoted just to annotating and “tabbing” books. The level of intensity and commitment varies; some BookTokkers have complex colour-coding systems (pink tabs and highlighters for romantic moments, blue for foreshadowing) or rules that are simply aesthetically pleasing. Some scribble in the margins to mark moments that are especially shocking or satisfying, or draw droplets or hearts around especially sexy passages. For some, annotation is as essential now as sharing shelfies or writing reviews.

Marcela, a Melbourne-based Bookstagrammer originally from the US, posts about her reading habits online as@booksta.babe. She began doing it last year after more than a decade of being active in fantasy and young adult fandoms, as well as “studygram” and other groups dedicated to beautiful-looking and complex notes and lists, created on nice stationery.

This article includes content provided byInstagram. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. To view this content,click 'Allow and continue'.

“Before I technically realised I was ‘annotating’, I would scribble little reactions and messages in the margins, so I could remember what I was thinking when I was experiencing a story or world for the first time,” Marcela recalls. Now she annotates usingcolour-coordinated tabs and pens, in addition to herreading journals. She’s selective with which books she puts this extra work into, sticking mostly to stories she knows she’ll reread – like her current annotation project, Sarah J Maas’ Throne of Glass series.

“It has really helped me enjoy the rich world-building and character development even more,” Marcela says. “You can clearly see my opinions on characters shift by following through my notes, and I love being able to refer back and see plot predictions I made at the beginning of the series either come true or be proven wrong.”

The dominant fandoms represented in the annotating and tabbing communities, as they are on BookTok and Bookstagram more broadly, are the booming romance and romantasy genres. Academic and author Dr Jodi McAlister says this is in large part because of the mainstream success of bestsellers like Emily Henry, Ali Hazelwood’s elevated-fanfic hit The Love Hypothesis, and Maas’ A Court Of Thorns and Roses series, which has helped to dispel much of the stigma that used to exist around reading romance novels. Fans are still working out ways to perform their fandom and find community, much in the same the way sci-fi and fantasy readers have been doing for decades.

“This is a community that is still figuring out what reading romance looks like in public because they haven’t had a model, and one of the ways it has manifested is this performance of love of the physical object of the book,” McAlister says; her latest romance novel, An Academic Affair, even includes a male scholar who “annotates his books like a BookTok girlie”.

“When we think about the way that romance has been denigrated as trash for so long, what they’re doing is performatively turning it into this incredibly treasured, incredibly valued object … by annotating it, you’re making thatyourcopy, you are memorialising your experience of it,” she adds.

It is what her fellow scholar Jessica Pressman calls“bookishness”: a post-digital behaviour that has developed among passionate readers. But that is not to say it is purely performative: annotating a novel can allow us to retrace our first journey with a book, as well as revisit our state of mind at the time. I think of the last book that made me cry,Meg Mason’s Sorrow and Bliss– what would my marginalia have looked like when I read it back in 2021, sobbing through the final pages at the reflections of my own struggles with mental illness? What would I see now in the notes I’d made then?

Annotation has also become a way of connecting: some BookTokkers lavishly annotate a copy of their friend’s favourite book as a gift, stacking the margins with observations and jokes; Marcela is excitedly planning to do this for her best friend. A dear friend of mine inherited the habit from his late mother and he now treasures the precious “scribblings” in the margins of her history and poetry books. Some people specifically seek out books annotated by other readers in secondhand shops – a spark of connection with the past – or even by their authors; last year, Ann Patchett released an annotated edition of her novel Bel Canto,though she warnedthat with “constant interruptions” and spoilers it was not designed to be anyone’s first experience. But annotating her own work, she wrote, revealed “patterns in the book I’d scarcely been aware of … it helped me clarify the way I write”.

I’m like McAlister, who says that while she annotates her academic reading, well, like an academic, she’s usually too immersed in books to annotate for fun. But this week I sat down with a pencil and got stuck into a biography of John and Sunday Reed I’d been passing over for more escapist fare. And I did, in fact, find myself jotting exclamation points in the margins at salacious details and scribbling in my judgy little asides like I was whispering to a friend.

If it feels a little like homework, maybe that’s not a bad thing. Even reading for fun alone could still be enhanced by the intentionality and slower pace required for annotation; the extra few seconds it takes to draw a star next to an especially satisfying paragraph lets you sit in that satisfaction, just a moment longer.