On any objective reading,Edward Burraoccupies a distinguished place in the history of 20th-century British art. His work, especially his watercolours of demi-monde life in interwar Paris and New York, is a distinct and vivid record of the times. His paintings are held in major institutions – as is his extensive archive, which is housed at Tate Britain in London.

And yet he remains “one of the great known unknowns of modern British art”, according to Thomas Kennedy, the curator of anew retrospectiveshow at Tate Britain. It is being held more than half a century on from Burra’s last show at the Tate in 1973, three years before he died aged 71. There are lots of reasons for Burra’s “unknown” status, explains Kennedy. “He worked alone, and not being part of a defined group doesn’t help to place an artist. But probably more important is the fact he absolutely hated talking about his work.” Kennedy cites some excruciating documentary footage (also from the early 1970s) illustrating Burra’s painful reluctance to engage with questions about art. “He just hated that stuff and would call art ‘fart’ and things like that. Apparently, he walked through that Tate show as if wearing blinkers, not looking at the work and just wanting to get it over with.”

The exhibition runs alongside a parallel show of works by Ithell Colquhoun, another radical British artist who, like Burra, challenged artistic conventions and explored parallel ideas of identity and sexuality in surrealist work that often reflected her occult beliefs.

The two defining features of Burra’s early life – he was born in 1905 – were the wealth of his family (prominent in banking) and the fact he suffered from extremely poor health. This combination resulted in him later being able to travel – to France and Spain, the United States and Mexico – then return home to Rye in East Sussex, where he spent most of his life, to recuperate after his exertions and paint the things he had seen.

His illnesses – rheumatoid arthritis and the blood disease spherocytosis among other conditions – also helped dictate the nature of his art in that it was physically easier for him to work with watercolours flat on a table than with oils at an easel. “As a watercolourist he pushed the boundaries of a traditionally delicate medium to create bold graphic works, rich in detail,” says Kennedy.

His illness also informed his empathy for those on the fringes of society and in his subject matter he engaged with some of the 20th century’s most significant social, political and cultural events. “After Paris in the roaring 20s and the Harlem Renaissance, he sort of pivoted to depict the violence of the Spanish civil war and then the second world war, before taking on British landscapes and reflections on postwar industrialisation and environmental degradation.”

While Burra was publicly reticent about his art, the Tate show’s exploration of his archives serves to deepen understanding of the man. As well as letters there are his gramophone records – mostly jazz – books and calendars he kept that show his obsessive cinema-going, sometimes seeing several films a day in French and German as well as English.

“Bringing these sources together is quite revealing,” says Kennedy. “It all adds to the tapestry of his influences and what emerges is a socially conscious art that is warmly satirical while also being willing to confront the darker side of life.”

Three Sailors at a Bar, 1930Burra’s sexuality is ambiguous, but his work in the 20s and 30s often reflected queer culture and sensibility. While this image of a bar in the south of France is among his more explicitly queer work, it also reflected a general sense of sexual liberation among Burra’s circle in the roaring 20s.

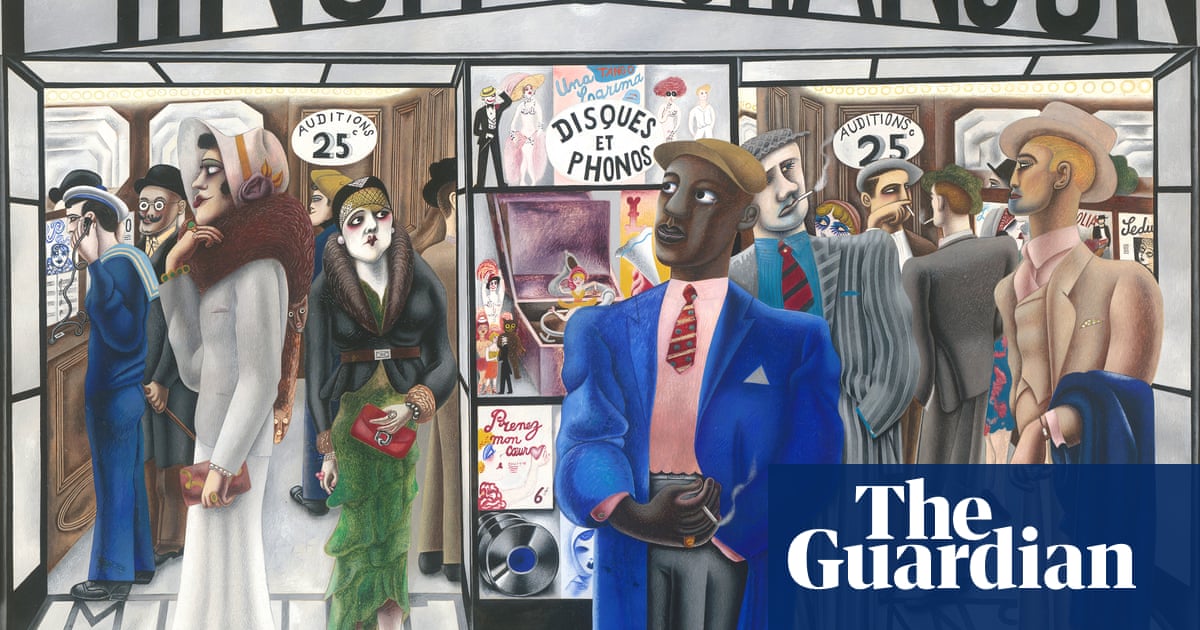

Minuit Chanson, 1931 (main image above)In this Parisian music shop where you could pay to listen to a gramophone record, Burra’s vibrant street scene celebrates its diverse clientele. In characteristic fashion, he deploys a satirical eye to heighten his subject matter rather than to cruelly caricature it.

Sign up toInside Saturday

The only way to get a look behind the scenes of the Saturday magazine. Sign up to get the inside story from our top writers as well as all the must-read articles and columns, delivered to your inbox every weekend.

after newsletter promotion

Beelzebub, c 1937Burra loved Spain and was devastated by the outbreak of the civil war, as he was to be again by the second world war a few years later. In this painting, he transforms historical Spanish conquistador imagery into a grotesque tableau accompanied by an unnerving sexual charge.

Cornish Clay Mines, 1970In his later years, Burra’s travel was restricted to motoring around Britain, and here he presents a commentary on postwar car culture, featuring ghost-like figures and advertising icons, such as the Michelin Man, all the while acknowledging his own participation in modernity’s environmental depredations.

Near Whitby, Yorkshire, 1972One of Burra’s final works shows an empty road disappearing into the fog. With lighter applications of watercolour than his earlier graphic style, possibly due to his declining health, the painting’s suggestion of moving into the unknown is typical of his later works in which he seems to be searching for moments of quiet reflection.

Edward Burra – Ithell Colquhounis at Tate Britain, London, 13 June to 19 October.