When the pandemic forced musicians all over the world to cancel tours, Warren Ellis decided to take his career in a new direction. From the bounds of his homehe co-founded an animal sanctuaryin Sumatra, Indonesia.

In 2021 theDirty Threevirtuoso and Nick Cave collaborator was introduced to the veteran animal rights activist Femke den Haas. Together they established the centre for old, disabled and displaced animals who couldn’t be released into the wild.

The sanctuary – Ellis Park – now lends its name to a documentary by the True History of the Kelly Gang film-maker Justin Kurzel: a stirring portrait of the park’s inhabitants and dedicated caretakers.

Immortalising Ellis’s poignant first visit to the park in 2023, the documentary traverses the lush vegetation of Sumatra and ventures to Ellis’s home town, Ballarat, and his studio in Paris, offering a glimpse into the life of a famously private Australian musician.

“I was very concerned at one point when we had half filmed it, and tried to get it stopped,” he says.

Kurzel first heard about sanctuary during a catchup with Ellis at the 2021 Cannes film festival. “Justin said to me, ‘I’m curious why you did it and I think the answer’s back where you were born,’” Ellis says.

Returning to the schoolyard of his childhood and to his parents’ home, the film’s first half shows Ellis reckoning with his past in real time. In striking, intimate vignettes, he reflects on the indelible influence of his father – a musician who sacrificed the seeds of his dream career to care for his young family, and who taught Ellis songwriting by singing verses from poetry books. “We filmed in there four days before the whole family disintegrated,” Ellis says, recalling his parents’ ill health and his father’s eventual death.

“I never thought I’d put that much of myself in [the film], and, as it transpired, the camera was on me when there were some big life things going on.”

It was a conversation with a film-maker and fellow Cave accomplice, Andrew Dominik, that soothed Ellis’s anxieties about being overexposed. “If you’re going to get something from it,” Dominik told him, “you’ve got to open yourself up to the process.”

When Ellis met Den Haas, the latter was running the SumatraWildlifeCenter, a “tiny” reserve that provided vital rehabilitation to injured wildlife, especially victims of abuse and the illegal exotic pet trade. During their first conversation, Den Haas told Ellis about a 5,000 sq m plot of land neighbouring the centre. He immediately promised to buy it and donate the land to provide essential housing for unreleasable animals.

“He said, ‘Doubts are toxic. There are no doubts; we just do it,’” Den Haas remembers. “Within two weeks, we started to look at the land and make the deal with the landowners.”

Within three or four months, the centre’s size had increased fivefold and the sanctuary was operational. About this time 1,300 trafficked animals were confiscated nearby.

For Den Haas, the timing was “magical”. With the sanctuary up and running, her team now had the resources to offer these animals – many of them captured in Africa – life-saving veterinary care and shelter.

Ellis Park provides a window into the lives of these animals and their caretakers, introduced in balletic, slow-motion closeups thanks to the deft, unobtrusive work of its cinematographer, Germain McMicking. “Not once was his presence felt; he just dances around everything,” Ellis says.

Sign up toWhat's On

Get the best TV reviews, news and features in your inbox every Monday

after newsletter promotion

While Den Haas has previously protected the animals from overreaching film crews, she appreciated the sensitivity of Kurzel’s team. “They really came and filmed things how they were … And when you’re watching the film, you get to see [the animals’] emotions and understand they’re all individuals and have a unique and horrific background.”

Ellis was conscious of the risks involved in documenting his own philanthropy: “The problem is, it’s very easy to make yourself appear a Bono-like character who’s just grandstanding.”

Upon his arrival in Sumatra, Den Haas welcomes him with open arms, inviting him to release an eagle rehabilitated by the centre. For Ellis, this posed a dilemma: he didn’t want to “look like some privileged guy that has built an animal sanctuary [to] blow out the candles [when] it’s not even my birthday”.

But with Den Haas’s coaxing, Ellis accepts the honour in the film’s moving climax. “He didn’t want to be in the spotlight, like, here’s the guy that made it all possible,” Den Haas says. “But he did make it all possible.”

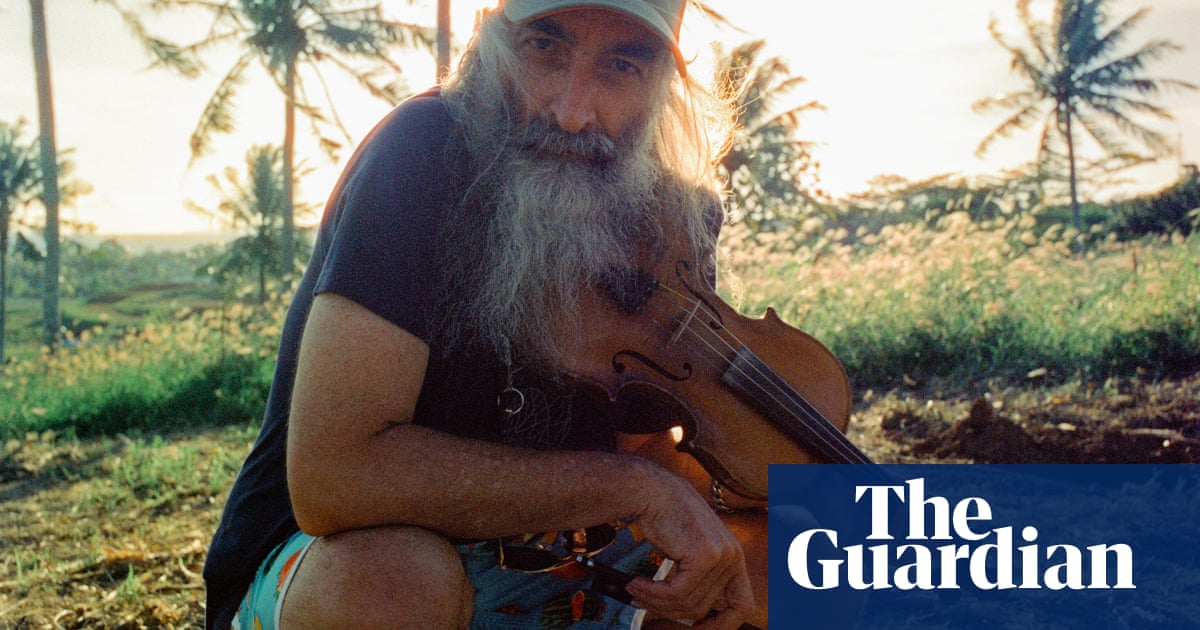

Ellis describes the film as an “accident” that developed organically through his trust in Kurzel. Accordingly, the documentary has a living quality. The score – by Ellis, of course – was recorded as it was made, with the musician shown tinkering on his violin in paddocks and monkey cages, as well as improvising in the studio. These images cede to scenes shot in Sumatra while the embryonic music lingers – a reflection of the sanctuary’s evolving form.

Working on a film “enables you to step out of that protective comfort zone that a band allows you to have and just do your thing for a common cause”, says Ellis, for whom “preciousness” is a young person’s game.

This common cause is clear in Ellis Park. Since the film was shot, the sanctuary has received an influx of bear cubs and baby gibbons whose mothers have been killed or injured by perpetrators of the illegal pet trade. Den Haas hopes it will soon shelter the bears in forested enclosures.

The sanctuary is still growing, and so is Ellis. “You know, I went over there expecting the film to be about abused monkeys and primates and birds,” he says, “and I left there realising the most extraordinary animals are people.”

Ellis Park is out now in Australian cinemas. The film will be released in the UK and Ireland in autumn 2025