Photography expert and Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Jeff L Rosenheim believes that cameras are profoundly entwined with the American story. “I’ve always been drawn to photography because it has this baseline democratic principle,” he told me. “It arrived from Europe in 1839, and what were we going to do with it? How did the camera play a role in us becoming the country that we hoped we would become?”

Rosenheim sees cameras as furthering the anti-aristocratic principles that America was founded on, in the process helping individuals own their identities and document their world. His new exhibition at The Met, The New Art: American Photography, 1839–1910, aspires to give us new ways of seeing precisely how that occurred. Dozens of portraits of everyday Americans showcase a fascinating people’s history of the United States, while also revealing a middle class deeply engaged in the process of discovering its identity, both as consumers and as participants in this young, quickly developing democracy. “Photographic portraits play a role in people feeling like they could be a citizen,” Rosenheim said. “It’s a psychological, empowering thing to own your own likeness.”

Covering a period when the US was figuring out exactly what photography was for, The New Art offers some 250 photographs that captures the day-to-day of the American experiment in action. In their immediacy and their frankness, these photos offer new possibilities for recording history that simply were not available before the invention of the camera. “The collection is just filled with the the everyday stories of people,” Rosenheim said, “and I don’t think painting can touch that.”

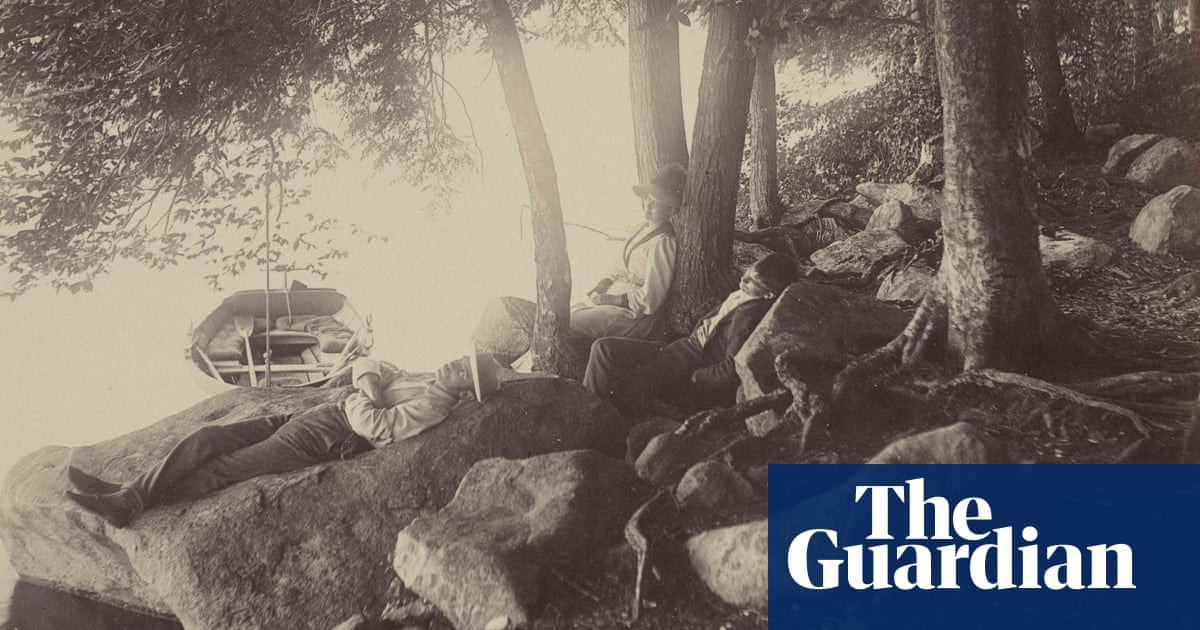

Although The New Art does include pieces by some recognized giants of the genre, it is largely comprised of the handiwork of unremembered and anonymous creators. The works are dominated by studio portraits – probably the only likeness of themselves a person of the era would have owned for their entire lifetime. Viewers will also be surprised to see the kinds of playful images that smack of people enamored of the possibilities of a new creative toy.

The latter category would include a memorable, if somewhat random, shot of a cow in a field, a dog standing on a chair and a sort of still life of a boot carefully placed into a roller skate. Rosenheim was particularly enamored of the boot still life for the sheer strangeness of it all. “It’s like, what is this picture, the mystery of this?” he told me. “The photographer had to solve a problem to make a still-life composition, so I love this. It’s like this fantastic object, and it asks more questions than it answers. In that, it’s very emblematic of the whole of 19th-century American photography.”

Indeed, one of the delights of The New Art is seeing so much individuality and personality brought to an era that is largely flattened into stereotypes of straitlaced vales and grim-faced visages. Although there are plenty of portraits redolent of the gravity of a once-in-a-lifetime event, there are also images that capture the true idiosyncrasy of the era: a shot of a man with his pet squirrel, the word “welcome” spelled out in what appears to be fern leaves, a man in a strange outfit simply labeled “Batman,” and a portrait of a cat snuggling a rabbit. They hint at hidden sides of US humanity that might well have been preserved in the historical record if people of the time had been able to make permanent images as simply and thoughtlessly as we can today.

“The social media aspect of our photography begins at its birth,” Rosenheim said. “Certainly in the United States, it was the people’s art.”

The New Art also shows the turmoil of a still young nation amid the pains and throes of a difficult coming of age. There are portraits of formerly enslaved individuals, including ones that show scars from the period before freedom. There is the curiously modern portrait of Lewis Payne, hands manacled as he awaits justice for conspiring to assassinate Abraham Lincoln. There is a street scene from the frontier town Brownsville, Texas, and numerous shots of Native Americans. “This is a medium that came of age before the civil war,” Rosenheim said, “then goes to that war, and is a part of reconstruction and thereafter.”

The photographs that Rosenheim is exhibiting are drawn from the William L Schaeffer collection, named for a largely unknown collector in rural Connecticut who amassed them over the course of 50 years. Rosenheim has known Schaeffer for decades and has long wanted to show his collection at the museum. “He just kept on putting away these photos like a squirrel,” Rosenheim said. “Things that he didn’t know whether they were common or uncommon because that history wasn’t told. He wasn’t buying most things at auction, he was finding them through flea markets.”

The exciting thing for Rosenheim is that the Schaeffer collection doesn’t just add to the collections of photographs that are already known – it opens up new frontiers in our understanding of what photography can be. “It’s a very idiosyncratic collection,” he said, “and it’s a canon-expanding production. What’s great about American photography is it’s an ever-expanding canon.”

The New Art is a delightfully varied and continually surprising exhibition that hints at just how much photographs may one day be able to show us, if collectors like Schaeffer and curators like Rosenheim continue to find and bring them to the public.

“I hear Walt Whitman when I look at these pictures,” said Rosenheim. “singing the songs of the people everywhere, whether it’s the butcher, the baker or the candlestick maker. That’s the poignancy, that’s where the pathos of this exhibition really hits me.”

The New Art: American Photography, 1839–1910 is on show at the Metropolitan Museum inNew Yorkuntil 20 July