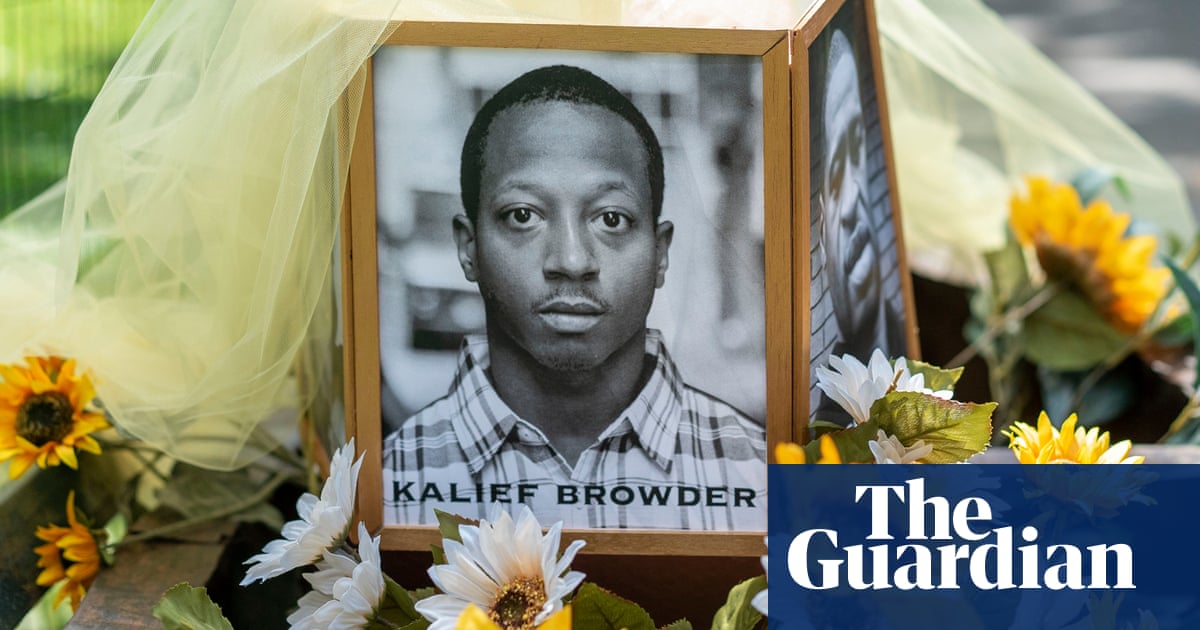

Premiering on the 10th anniversary of Kalief Browder’s death, the poetic and thought-provoking documentary For Venida, For Kalief transcends time to tell the story of Kalief through the poems written by his mother, Venida.

The film opens with tender scenes of a carnival in New York City during the reading of Venida’s poems by Jasmine Mans. “My heart aches for what he went through, headaches that I couldn’t prevent. It aches that he is no longer here. How often I relive the steps I took to find him hanging out of the back window of the second floor, just lifeless.”

The director Sisa Bueno met Venida after intuition led her to attend a Q&A where Venida was speaking about the death of her son. “In this case, being late, everything was full, the whole auditorium was full, and there was literally one seat at the very front,” she recalls. “It was like it was waiting for me.”

She adds: “At that moment, at the Q&A part, someone was like, ‘Well, how do you get through this?’ and [Venida] said, ‘I write poems.’ I just started getting New York scenes that I knew I grew up with in my mind’s eye. I didn’t even hear her poems, but I just figured they would kind of mesh well. And that was it. Then I had a creative spark.”

On 15 May 2010, police arrested Browder when he was going home from a party in the Bronx, New York, after being accused of stealing a backpack. Authorities charged him with robbery, grand larceny and assault. The city set his bail at $3,000. However, when his family attempted to pay the bail, he was not released because he had been on probation for a previous charge.

He was held on Rikers Island until 2013 and faced beatings by guards and other inmates. Browder spent 800 days in solitary confinement. The charges were eventually dropped and he was released, but the mental agitation he faced while in jail stayed with him and later led to his suicide. Venida died a year later.

Bueno, who got to know her well, was at the hospital the day she died. Bueno says Venida’s death motivated her to finish the film. Kalief was her adopted son. He came to her home after the city placed him under the care of Child Protective Services due to his birth mother’s drug addiction. People close to Venida say her death was a result of witnessing the brutal and inhumane treatment of her son.

While the poems act as the guiding force for the audience, the visuals used by Bueno gives a new perspective on Kalief’s story and places it in a broader historical context. The archival footage of the Citywide Jail Rebellion in 1970 found by archival producer Mattie Akers, shows prisoners across Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens and Rikers Island protesting the poor living conditions of the NYC prison system, mirroring the experiences that Browder had in his three years on Rikers. The protesters held people hostage in the jail system while demanding to speak to the mayor about the inhumane conditions to orchestrate systemic change.

“It seem[ed] like the correct thing to do [was] to really bring this moment out and sort of juxtapose that with today, let people understand that this is a systemic issue,” Bueno says. “We all know it, but really, when you see the past and the present kind of mirror each other, it becomes very clear that the system is systemic and it’s highly problematic, and it’s not just a new issue.”

Though the mayor never met with the prisoners, at the end of the documentary, we learn that those accused of leading the rebellion were acquitted of all charges, leaving the viewer with a renewed idea of the power of collective advocacy.

“At that point in the 60s and 70s, a lot of people were struggling … but we ended on something that was for the public good, for the most part,” she says. “People had a sense of power when they were organizing together and understanding about what it was they were fighting for.” However, she feels the opposite is occurring now and wants to remind people of the power of collective mobilization.

She hopes the documentary not only brings awareness to Kalief’s death but also serves as a call to action for others to remember his story. “I want to do something that is actually solutions-based because that’s my theory,” she says. “I don’t want to do something that’s just reinforcing, a triggering feeling where people are left numb after watching a film because that’s usually how I feel when I watch most criminal justice films.”

Through José López, Bueno offers the viewer a practical way of honoring Kalief’s story. López is the enrollment manager at the Future Now program at Bronx Community college (BCC), the same school Kalief attended. The pair met while he was a mentor in the College Now program when they both attended BCC. He now asks students to wear buttons with an image of Kalief at graduation to commemorate him. Bueno argues that wearing a pin is an everyday act that anyone can participate in.

“He has to be remembered,” López says.

Despite moments of hope, the documentary also shows slow progress towards justice. In October 2019, the New York City council passed a law to shut down Rikers Island. The Renewable Rikers Act transfers control of the island from the department of corrections to other city agencies and environmental justice advocates.

In the same year, the passing of Kalief’s Law mandated that prosecutors give the defense every piece of evidence before trial to increase the speediness of the court system, but in 2025, Kathy Hochul, the New York state governor, proposed scaling it back.

Although the New York City council voted to ban solitary confinement in December 2023, Eric Adams, the mayor, issued a state of emergency blocking its implementation. There are plans to build a new jail in Chinatown in 2032 after the closure of Rikers in 2027, expanding the former Manhattan detention complex. Chinatown residents are now protesting against the construction of the new prison in their neighborhood.

Through Venida’s heart-wrenching lyrical poems and Bueno’s visionary storytelling, the film depicts the reality of the unbalanced NYC criminal justice system while honoring Kalief’s story to create a call to action for a change in the city’s prison system, reminding viewers of loss and possibilities. “Real life is about push and pull,” Bueno says. “Two steps forward, [one step] back. That’s a real thing. You can’t deny that that’s true. And that doesn’t mean you don’t still move forward.”

For Venida, For Kalief premieres at theTribeca film festivalwith a release date to be announced