Among the African writers who emerged in the middle of the 20th century, the most political undoubtedly was Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. Born in Kenya while it was still under British rule he was anti-colonialist, a communist, anti-dictatorial, and an almost militant proponent for African languages being used for African literature.

His best works exist at the interface between the political and the personal. His first book of essays, Homecoming, is at once engaging and polemical. His early novels Weep Not, Child and A Grain of Wheat look at the impact of colonialism and the Mau Mau rebellion on individual lives. He was strangely at his best with the personal and the intimate, but his reputation grew more from his political stances – first against the British government, then against the dictatorship in Kenya in the 70s. He was jailed not for a thundering political text but for a play in Kikuyu called I Will Marry When I Want. In prison he wrote his memoir on toilet paper.

When I first met him I expected to meet a socialist firebrand but instead encountered a genial, engaging man who had read some of my writing and asked about my influences. I was genuinely surprised by his warmth, his humour and his friendliness. He was at ease with white as well as black people. He loved a good drink, enjoyed conversation and had a genuine love for literary small talk.

I first knew him after his release from prison during his time in London. At the African Centre he would have a coterie of political acolytes and well wishers who wanted to ease his time in exile. I had conversations with him about literature. He was interested in my reading. I remember one particular conversation. At the time I had only published my first two novels and I was in my early 20s.

“What novels do you read?” he asked.

“All of you.”

“Who else?”

“Tolstoy, Dostoevsky.”

“Which Dostoevsky?”

“Crime and Punishment.”

“Did you read that before or after you wrote your second novel?”

And I froze. The question made me aware of something that I had not considered before: the implied relationship between the greatness of the books you have read and the quality of the books you write after reading them. I suddenly felt ashamed that the novel I had written did not do that reading justice. Whatever answer I gave was a chastened one.

Sign up toBookmarks

Discover new books and learn more about your favourite authors with our expert reviews, interviews and news stories. Literary delights delivered direct to you

after newsletter promotion

Ngũgĩ would paralyse you with an innocent-seeming question. They said Bertolt Brecht was like that too. In his gentle way Ngũgĩ compelled you to come up with cogent answers to the probing remarks he made about African literature and the question of language, a question of authenticity. In his company you could not be lazy.

He also took an interest in my pool game and would often place bets on me in pubs in Covent Garden. Between frames we would talk about books. He had an almost mystical awe for what Achebe achieved in Things Fall Apart. Looking back to a time when the only literature being taught at universities was Dickens and Conrad et al, he made me feel how thrilling it was to read for the first time this novel that had found a language to express the yearning of Africans for their own story.

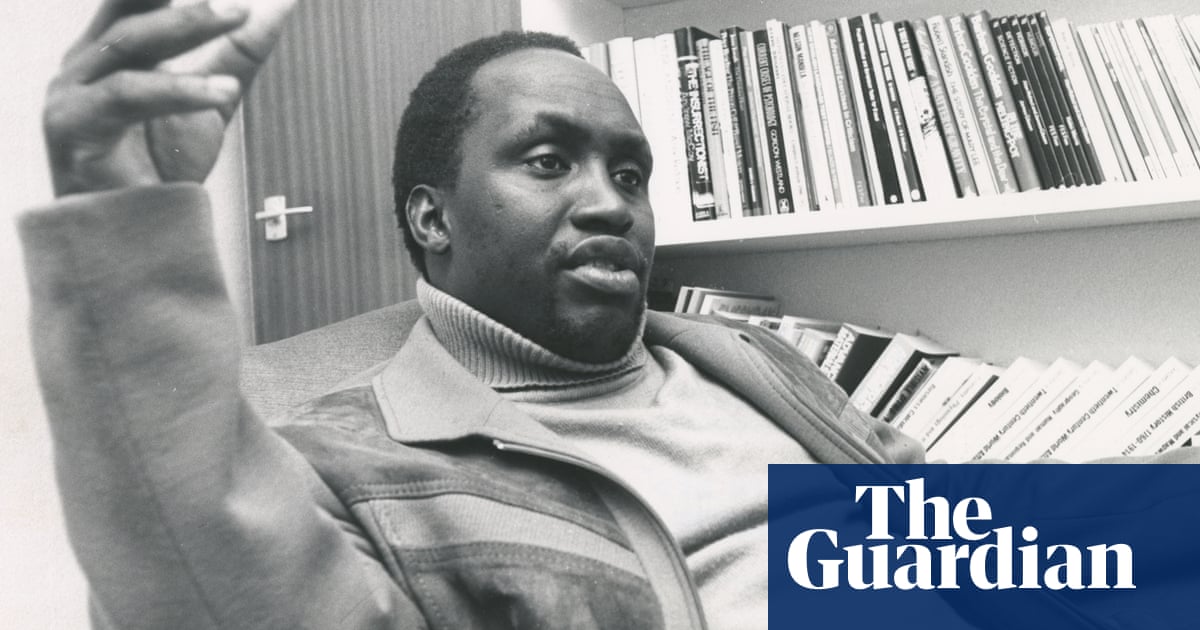

By that time he had become a slightly portly figure with interrogative eyes and ready laughter. He tended to wear African tops and western trousers. One got the feeling with him that he had done a lot of his political thinking early but was open to the discoveries that his work led him into.

He began his writing life as James Ngugi, and metamorphosed into Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. He began writing in English and ended by writing in Kikuyu, often having to translate himself. His anti-capitalist stance didn’t stop him becoming one of the most feted African writers in America. And in all of this, the one constant was that he remained a likable man without pretensions, and always with a feeling for the common people.

Towards the end of his life, he became a perennial favourite to win the Nobel prize, and like Borges, had to endure the rise and fall of expectation every October. Family tragedy also marred his later years. But perhaps my fondest memory is of sitting with him in a Cambridge college during a Callaloo conference. We began talking about music and literature and he surprised me by saying that he was learning to play the piano for the first time. He was then in his mid-70s. He talked about the wonder of going from being unable to play a note to being able, within a few months, to play some Mozart, Chopin and Bach. It was very affecting to hear this seasoned revolutionary take on a youthful glow as he talked about this new-won skill. There happened to be a piano in a corner of the hall, and we went over. To this day I can still see him with a light smile on his face as the Bach notes tinkled into the hall.