In April 2013, Nudrat Afza, a Muslim woman from Bradford, gave her 90-year-old Jewish friend Lorle Michaelis a lift to the local Orthodox synagogue. “As Lorle got out of the car, she told me it would be the last service,” Afza recalls. “There were no longer enough people to run them. I was shocked. I knew the building would be sold or demolished.”

Afza got out of the car and took a few quick photos of the synagogue’s exterior. Months later, she happened to be passing when the caretakers were coming out. “I put my foot in the doorway and took some pictures inside, to quickly record what was there,” she says. The Orthodox synagogue was sold and redeveloped in 2015. Afza didn’t know it at the time but the photos were the start of a multi-year project to document Bradford’s declining Jewish population. “I grew up looking at pictures of the 1960s civil rights movement in the US, the Vietnam war and other political struggles in Britain and south Asia,” Afza explains. “I saw the importance of documenting something before it disappears.”

It had previously looked as though the Bradford Reform Synagogue, in the diverse inner-city area of Manningham where Afza lives, might also go the same way. In 2011, the Grade II-listed building needed extensive work to fix a leaking roof. When the synagogue’s remaining few members couldn’t afford repairs, the Muslim community stepped in to donate funds, which was followed by a £103,000 National Lottery Heritage Fund grant. Built in 1880-1881, the Reform Synagogue is now the only remaining synagogue in Bradford, with about 30 members.

Afza’s photos from the synagogues and Scholemoor Cemetery, all shot on film using vintage cameras, are collected together in her new book, Kehillah (Hebrew for “congregation” or “community”). She’s keenly aware that “a Muslim woman taking photographs of the Jewish community” might jar with the common narrative that Jews and Muslims don’t get along. “In Bradford, people from different communities respect each other,” she tells me. “When I came to Bradford, when I was 10, I was aware of other religions, as well as my own, and we had nothing but respect for that. I was aware I was an outsider, so I was sensitive to what I did and how I did it.”

Kehillah has an elegiac quality. “A lot of the people have died since the photographs were taken,” says Afza. “When I came on the scene, you could count on your fingers the Jewish people at Bradford Reform Synagogue’s Saturday services. I felt that if it wasn’t recorded, it would disappear.”

Born in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, in 1955, Afza moved to Bradford in 1965. By chance, she picked up a camera in the mid-1980s.Simon Beaufoy, the Oscar-winning screenwriter behind The Full Monty and Slumdog Millionaire, later saw Afza’sSalonseries – a project documenting the final year of a local establishment, Kenmore Salon, before it was sold in 2012 – and got in touch to offer his support. “[Beaufoy] told me that I have talent and gave me a Hasselblad XPan camera.”

Afza’s documented others slices of northern life, including female football fans in Bradford City’s stadium (City Girls), derelict buildings (Ruins Oof Bradford)and a personal project,Cancer: Shadow Aand Light, which followed her sister Sairah’s treatment for breast cancer. Afza’s work was produced during tightly restricted intervals: a mother of two, she spent more than three decades as a full-time carer for her daughter, Khadijah, who was born with a life-threatening liver condition. “With the Salon pictures, the hospital was right across the road from the salon, so I’d leave my daughter in hospital and say, ‘I’ll be right back’, and go off and take some photos.” Khadijah died in January 2025, aged 35. “With my first pictures that I took, she was in my arms, very poorly, in hospital,” Afza remembers. “I’m a bit of a recluse, so whenever I got my contact sheets, she was always the first person who saw them. She would look at them and tell me which ones she liked.”

This year, Bradford is the UK city of culture. The place has been known in the past for racial tensions but Afza hopes it’s on the up. “I love Bradford,” she says. “There’s a wide range of communities today and they do their best to work together and make the most of things. It just needs a lot of money pumped into it: schools, hospitals … Looking after my daughter in the hospital, we were on the receiving end of a lack of resources and expertise. Despite that, I’m optimistic for Bradford.”

KehillahbyNudrat Afzais published byDewi Lewis (£30)The Kehillah photographs will be exhibited at theDean Clough Galleries, Halifax,16 August to 19 October.

Chanukah ServiceBradford Reform Synagogue, Bradford, 2018This is a photograph of Suzie Cree, the chair of trustees at the Bradford Reform Synagogue, taken at the end of a Chanukah service. It was taken very late in the evening. Everybody else had gone home. I saw Suzie come to blow the candles out. The photo captures a moment in time and resonates with the decline in numbers of Jewish people in Bradford.

CoveredBradford Reform Synagogue, Bradford, 2018“The men do this when they come to the synagogue. They’re covered by the Tallit prayer shawl, as a way of expressing reverence and awe of God during prayer. It’s put right over the head and a blessing is recited: ‘Blessed are you, Adonai, ruler of the universe who has commanded us to wear the Tallit,’ which is then lowered to the shoulders. I think it’s an image that the outside world doesn’t see.”

Jewish Burial SpaceJewish burial space in Scholemoor Cemetery, Bradford, 2018“The cemetery contains the tombs of Jewish people from many generations who lived in Bradford. The picture is just so evocative. I like the shape of the photograph, with the ground covered in frost, the trees with their branches and leaves, and the mist creating an eerie atmosphere. It’s quite a mournful image. It looks beautiful and haunting at the same time.”

TabletBradford Reform Synagogue Bradford, 2018“I took this as I was walking past the two children – just one snap. Initially, when you look at the image, your reaction is that they’re praying. But, in fact, they have a modern gadget and they’ve both got earphones in – they’re watching or listening to something on their tablet.”

TorahBradford Reform Synagogue, Bradford, 2018”This is the Torah being unrolled to select the reading for the Shabbat service. The Torah is the Jewish sacred text. This Torah is about 150 years old. Its staves are made of wood and the scroll is adorned with silver. As a photographer, I wanted to capture these details.”

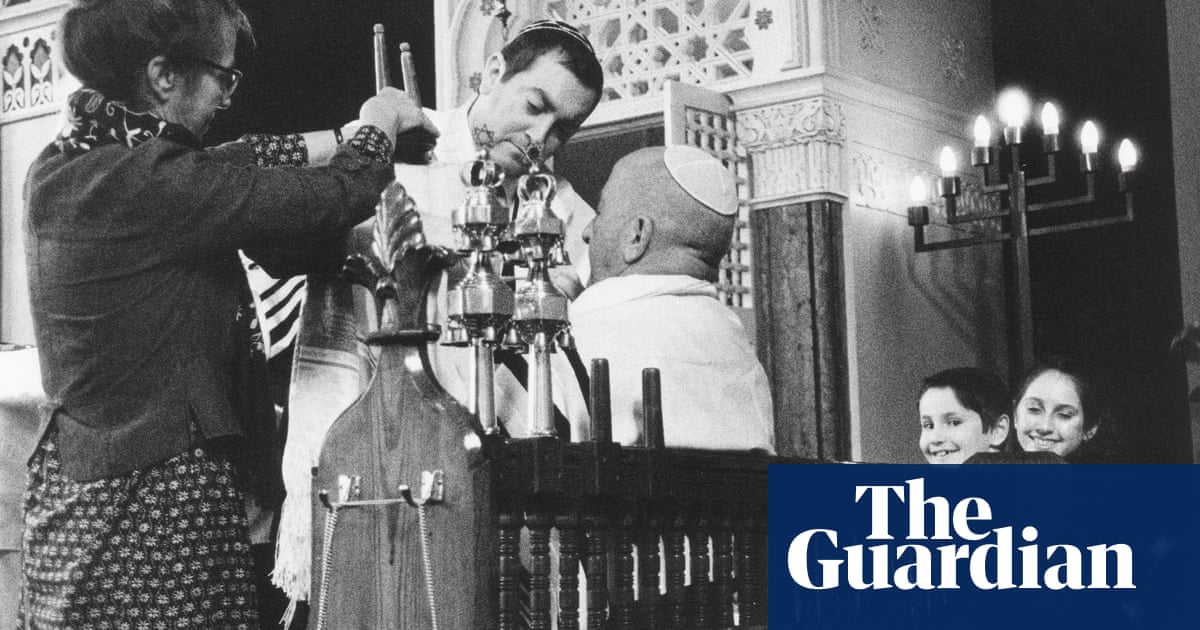

Dayof Atonement (main image)Bradford Reform Synagogue, Bradford, 2018”I absolutely love this picture. It’s taken on the Day of Atonement or, in Hebrew, Yom Kippur. There’s modern and old mixed together – you have the old architectural details in the background and the electric menorah on the right-hand side, which gives a surreal feel to the picture. It’s not posed or contrived.”