Guantánamo is a horror Americans have tried to forget. But the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (Ice) deportation regime resembles so many of Guantánamo’s evils that it compels comparison. That comparison reveals significant differences but frightening similarities.

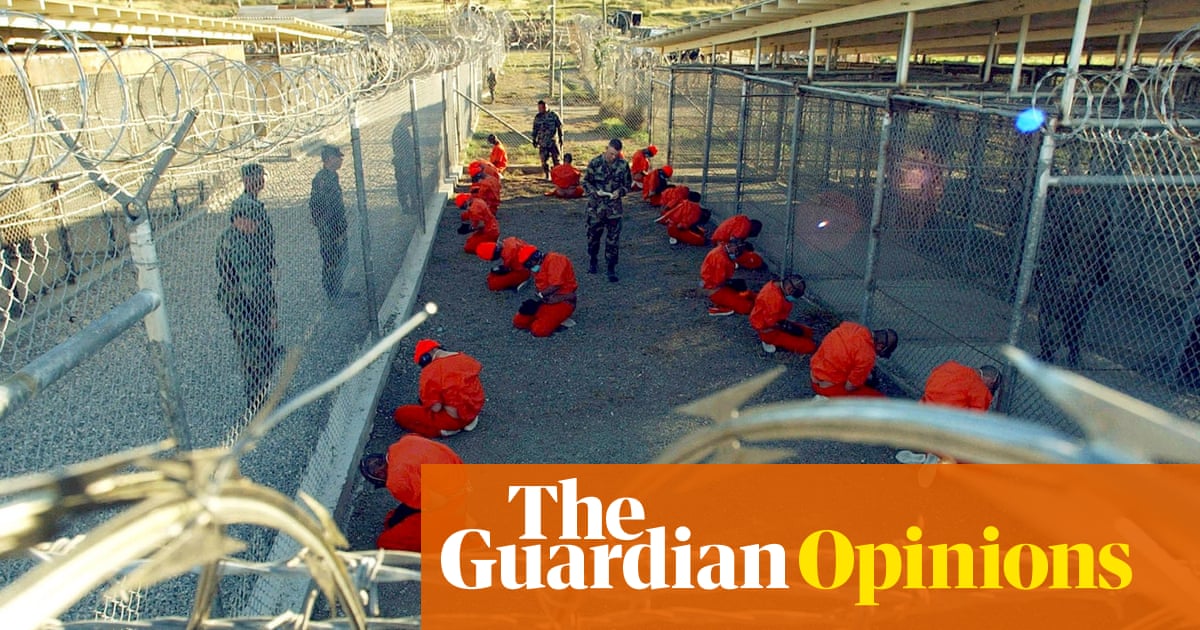

On 11 January 2002, the detention facility opened. The first detainees, in orange jumpsuits, hobbled along in a parade to show the press the success of the government in this battle of the “war on terror”.

Despite this dramatic perp walk, there were very few actual terrorists among that group. Indeed, very few real terrorists were ever brought to Gitmo. No hearings, proceedings or reviews were held for any of these initial detainees to determine why they were included. What mattered was not the truth but the photo op.

I represented four individuals detained for almost 20 years in Gitmo, so it was not surprising that I reacted viscerally to the sight of people abducted on the streets of my own country by unidentified men in civilian dress; shackled and then shoved into unmarked cars, driven to secret locations, and held incommunicado, including being cut off from families and lawyers.

Gitmo was a military base outside the United States and chosen for this purpose because it seemed unlikely that the constitution reached actions involving foreigners there and because any press access could be tightly controlled. That enabled the systematic demonization of detainees, which was critical to denials of any hearing to them.

Such demonization was such a success for Gitmo that the first lawyers arrived believing we were meeting monsters. Most attorneys left their first encounters with their clients believing that, while other detainees must be demons, each lawyer’s own client was the unfortunate victim of a mistaken arrest. It was only much later that it became clear that such “mistakes” were the rule, not the exception.

For me, the truth emerged one night when sitting outside the barracks under a star-studded Cuban sky with other lawyers talking about their client visits. We could talk to each other only while at the Gitmo naval base; our secret clearances forbade reporting anything about our clients when we returned home. One said: “I know that there are bad guys here, but my guy is not one. I don’t know why he is here.”

I was relieved to hear that, because neither of my two clients deserved to be there, either.

The next day, during my visit, my client asked why was I there and what could I do for him. I explained that the supreme court had allowed him to have a lawyer to represent him. He was unimpressed: “And if you win in court for me, what good will winning be? How big is the supreme court’s army?’

Even today, some don’t recognize the wholesale deception of labelling the great majority of Gitmo detainees “terrorists”. When forced, years after the first detentions, to produce its basis for detention for one inmate, the only claims the government made, in their entirety, were:

Detainee is associated with the Taliban

I The detainee indicates that he was conscripted into the Taliban.

Detainee engaged in hostilities against the US or its coalition partners.

The detainee admits he was a cook’s assistant for Taliban forces in Narim, Afghanistan under the command of Haji Mullah Baki.

ii. Detainee fled from Narim to Kabul during the Northern Alliance

Scarcely a claim that the detainee was a terrorist, not to mention that the truth of those claims has never been tested. This individual was simply released, quietly, many years later.

This person was not an atypical detainee. Only 5% of those detained in Gitmo were captured by US forces; the others were turned over to us by Afghan tribal chieftains, warlords and local officials for large bounties, meaning there was often no way to determine if allegations were true and no way to test whether, even if true, they were sufficient to warrant lengthy detention. Indeed, theUS government’s own evidenceestablishes that only 8% of those brought to Gitmo were al-Qaida fighters. Even the government admits that at least 55% of all Gitmo detainees were never accused of a single hostile act against the US or its allies.

That brings us to the current demonization of many migrants, frequently denied essential procedural rights. These migrants have been moved outside the US, and the complete absence of legal procedures has enabled the government to conceal its many mistaken deportations. The need for process is especially crucial because tragic mistakes have already been uncovered and these ad hoc discoveries show how often, and how easily, people can be wrongfully captured, detained and deported based on untested allegations from some unknown and unaccountable bureaucrats. Unlike Gitmo, the government has not been completely successful in cloaking its actions with secrecy and the limited record that we have suggests that, once again, mistakes are the rule, not the exception.

Kilmar Ábrego García is a Salvadorian citizen, legally in the United States, married to an American citizen, and father of three children, also American citizens; a five-year-old boy with severe autism and deaf in one ear; a nine-year-old boy with autism; and a 10-year-old who has epilepsy.

Ábrego García had been granted a court order protecting him from deportation because he had a well-founded fear of gang violence in El Salvador. However, he was sent there in what the Trump administration calls an “administrative error”. The administration has refused to correct its error because Ábrego García is being held in a foreign country and the administration claims it had no ability to compel his return. Federal courts ordered his return to the United States and to his family, but the administration still refused and appealed to the supreme court. The supreme court issued an order that the government must “facilitate” Ábrego García’s return.

There is no evidence that the government will do so. But compliance with the supreme court is essential. Otherwise, my Gitmo client’s question resonates: “How big is the supreme court’s army?”

Mark Denbeaux is professor emeritus at Seton Hall Law School and for 18 years represented four detainees held in Guantánamo who had endured torture by the CIA