Götz Valien is Berlin’s last movie poster artist, for more than three decades earning a modest living producing giant hand-painted film adverts to hang at the city’s most beloved historic cinemas – a craft he says will probably die with him, at least in westernEurope. The studios’ own promotional posters serve as a template, but Austrian-born Valien, 65, adds a distinctive pop art flourish to each image coupled with the beauty of imperfection – part of the reason he has managed to extend his career well into the 21st century.

“Advertising is about drawing attention and I add the human touch, which is why it works,” he said. Valien’s work plays up the image’s essence: the imposing bow of a ship, the haunting eyes of a screen siren, a mysterious smile. He jokingly calls himself aKinosaurier– a play on the German words for cinema and dinosaur.

His nearly-7x9-metre canvases long-graced the “film palaces” of the German capital, including the majestic Delphi in the west and the socialist modernist masterpiece Kino International on Karl Marx Allee in the east. But the former’s adverts finally went digital in 2024, while the latter is closed for a years-long, top-to-bottom revamp. Dozens of independent cinemas among his clients have simply gone out of business. The century-old Filmtheater am Friedrichshain (FaF) is the last movie theatre in Berlin still employing Valien to tout its new releases, with his large-format posters covering its facade and interior walls around the ticket-and-popcorn counter.

Gazing up at his rendering of the kohl-eyed, flower-rimmed visage of Penélope Cruz from Pedro Almodóvar’s 2006 melodrama Volver, a classic still hanging in the lobby, Valien sighed: “Isn’t she magnificent?”

Beyond vestiges of a proud tradition in countries such as Ghana, Nepal and India, Valien said only a vanishing number of movie theatres worldwide still used hand-painted posters. He knows of only two colleagues in Germany: in Munich and Bremen. “Paris, Portugal – they all say sure, we had them, but those days are over.”

The FaF manager, Andreas Tölle, said the posters had become a cherished part of the neighbourhood. “People now come by when the new ones are up and take pictures,” he said. “And that fascination also brings people into the cinema.”

Movie posters have existed as long as the nearly 130-year-old film industry. But these days, few releases stay long enough in cinemas to justify bespoke art to advertise them, communications studies professor Patrick Rössler of the University of Erfurt, who has studied the history of film posters, told local media. And most independent cinemas don’t have the profit margins to afford them, even at what Valien calls his bargain-basement prices.

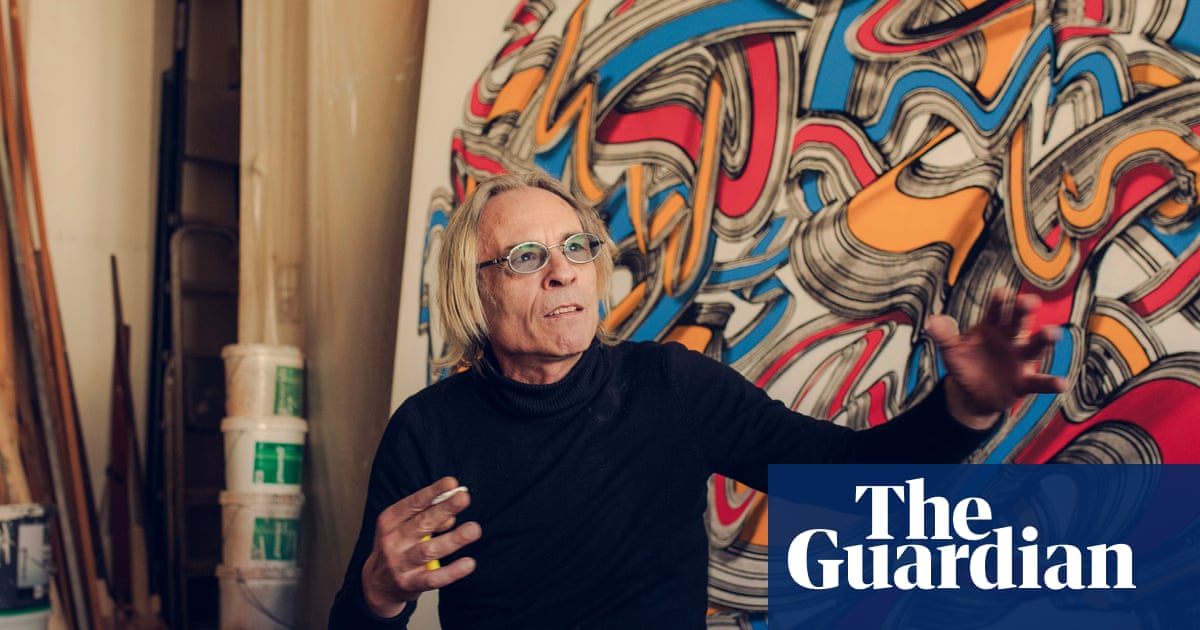

Back at the home studio that he and his wife, Silke, bought decades ago in the heart of the Schöneberg neighbourhood’s historic queer red-light district, Valien recounted his arrival in West Berlin in the 1980s. When the Wall finally fell, he was unimpressed with what he found in the east. “It just seemed sad and colourless, and then one day I realised what was missing – the billboards,” he said.

After failing to gain admission to film school – “in my opinion, the avant garde had lost its way – it got too philosophical,” he said – Valien returned to his first love, painting, which he had learned in Vienna using “old master techniques”.

In the early 1990s, he found work with an advertising firm – one of two Berlin studios producing painted movie billboards. His first poster was for Steven Spielberg’s Hook, and Valien quickly gained a city-wide reputation as he churned out photorealistic posters in just two days, in time for the movies’ releases on Thursdays. “Not to brag, but I was a Ferrari among horse-drawn carriages,” he said of his competition. After the death of two elderly colleagues, Valien found himself the last man standing.

In his heyday he could ride down the elegant Kurfürstendamm, once home to dozens of cinemas, and all the film billboards up and down the boulevard were his handiwork. “Now they’re H&Ms, Zara, Tommy Hilfiger …,” he said.

The spectacular success of the 1997 blockbuster Titanic nearly broke his business as it stayed in the cinemas for months, blocking new releases in need of fresh posters. Last year, Valien finally had to give up a much larger dedicated studio and an assistant as the orders dwindled. There he had used a mechanical lifting platform to cover the floor-to-ceiling canvases. “Painting almost every day in that huge format is like running up Mount Everest barefoot,” he said. “Exhausting.”

Valien estimated he has created more than 3,000 posters over the years using the acrylic paints that lie scattered among the brushes and spray guns around his sunlight-flooded workshop. He declined to say how much he earns per poster, but says his film work is essentially “non-profit” and a “labour of love” while he pursues other art projects.

He remains unsentimental about the posters themselves, noting that he used to simply paint over previous works to save money on canvases. FaF has a small archive while Valien maintains anactive Instagram accountshowing himself in ironic, hammy poses in front of his work. In honour of its 100th anniversary and Valien’s decades of service, FaF is running aMovies on Canvas homage seriesof screenings paired with an exhibition of some of his best-loved posters: Walk the Line, Frances Ha, Brokeback Mountain, Little Miss Sunshine and, not least, The Artist.