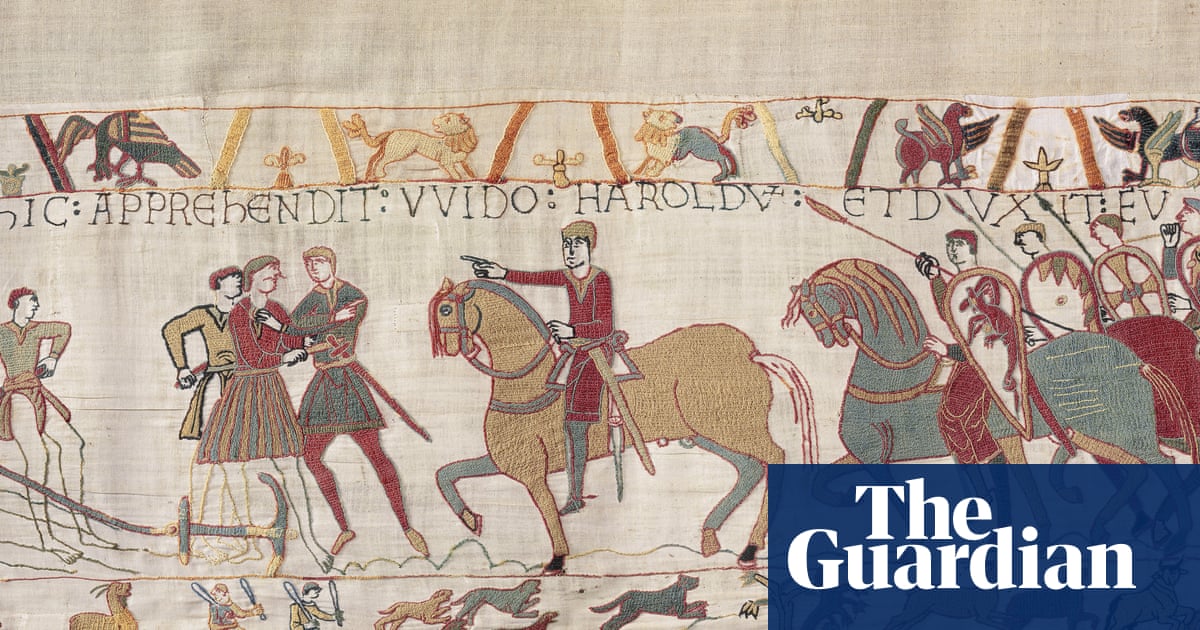

In a historical spat that could be subtitled “1066 with knobs on”, two medieval experts are engaged in a battle over how many male genitalia are embroidered into theBayeux tapestry.

The Oxford professorGeorge Garnettdrew worldwide interest six years ago when he announced he had totted up 93 penises stitched into the embroidered account of the Norman conquest of England.

According to Garnett, 88 of the male appendages are attached to horses and the remainder to human figures.

Now, the historian and Bayeux tapestry scholarDr Christopher Monk– known as the Medieval Monk – believes he has found a 94th.

A running man, depicted in the tapestry border, has something dangling beneath his tunic. Garnett says it is the scabbard of a sword or dagger. Monk insists it is a male member.

“I am in no doubt that the appendage is a depiction of male genitalia – the missed penis, shall we say. The detail is surprisingly anatomically fulsome,” Monk said.

The Bayeux Museum in Normandy, home to the 70 metre-long embroidery, says: “The story it tells is an epic poem and a moralistic work.”

The historians, whose academic skirmish takes place in theHistoryExtra Podcast, both insist that – beyond the smutty jokes and sexual innuendo – their work is far from silly. Garnett said it was about “understanding medieval minds”.

“The whole point of studying history is to understand how people thought in the past,” he said. “And medieval people were not crude, unsophisticated, dim-witted individuals. Quite the opposite,.”

He believes the unknown designer of the epic embroidery was highly educated and used “literary allusions to subvert the standard story of the Norman conquest”.

He said: “What I’ve shown is that this is a serious, learned attempt to comment on the conquest – albeit in code.”

In theBayeux tapestry, size did matter, Garnett said. He pointed out that the battle’s two leaders – Harold Godwinson, who died at Hastings with an arrow in his eye, and the victorious Duke William of Normandy, AKA William the Conqueror – are shown on steeds with noticeably larger endowments. “William’s horse is by far the biggest,” Garnett said. “And that’s not a coincidence.”

Monk insisted the running man’s dangly bits are the tapestry’s “missing penis”.

Dr David Musgrove, the host of the podcast and a Bayeux tapestry expert, said the new theory was fascinating.

“It’s a reminder that this embroidery is a multi-layered artefact that rewards careful study and remains a wondrous enigma almost a millennium after it was stitched,” he said.