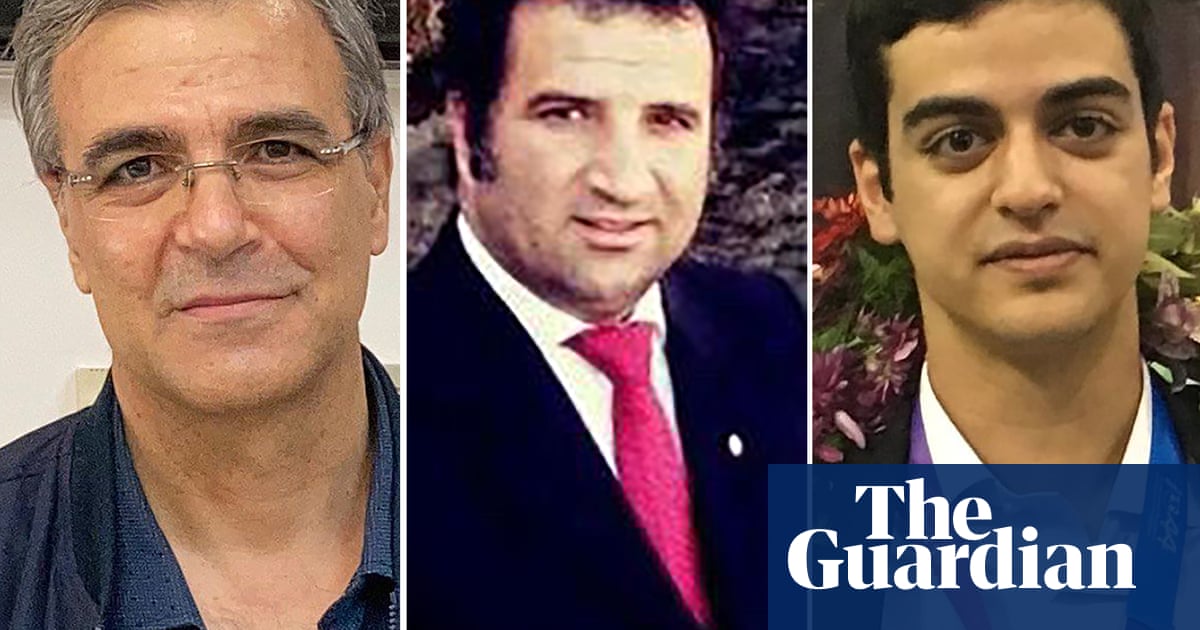

When Mehraveh Khandan heard about Israel’s evacuation order in Tehran last week, the first thing she thought of was her father. Reza Khandan, imprisoned for his human rights activism in 2024, was sitting in a cell in Tehran’s Evin prison on the edge of the evacuation zone.

She fielded calls from her friends, who were breathless from the shock of the Israeli bombs as tens of thousands fled the Iranian capital. Her father, by contrast, had no way to flee. He was stuck.

“It was the most helpless and trapped moments in my entire life. That was the clearest image for me of our situation as Iranians: one captures us, so the other can strike us,” the 25-year-old said from Amsterdam.

On Monday, Mehraveh’s worst fear was realised when Israel struck Evin prison.

Grainy CCTV footage showed the entrance exploding and the gate crumbling, with Iran’s judiciary confirming damage to parts of the prison. Relatives of prisoners told the Guardian there were injuries reported in wards four, seven and eight – where Reza was being held, though he was unharmed.

“Their heads are slightly injured from the force of the explosion, the blast wave caused their heads to hit the wall and swell,” said Hussein*, an Iran-based relative of the human rights lawyer Mohammed Najafi, who is imprisoned in ward four. “The prisoners are worried.”

The Guardian could not independently verify claims of injuries within the prison.

Mehraveh is just one of many whose family members were detained for political reasons by the Iranian government. They now fear for the safety of their loved ones stuck in prisons, unable to flee the bombs.

The Israeli defence minister’s office said the prison attack was part of a larger assault on “regime targets and government repression bodies in the heart of Tehran”.

Detainees and human rights activists have called for the temporary release of prisoners until fighting has stopped.

A group of detainees, including Reza, sent a letter to the head of Iran’s judiciary on Wednesday calling on him to temporarily release prisoners, citing an Iranian law that allows for conditional releases during war time.

“Prisons are not equipped with air raid warning systems, shelters or safe evacuation routes … especially ward eight of Evin prison, which is in an even more vulnerable state and does not even have a single fire extinguisher,” the letter read.

Mehraveh and other family members of detainees were not optimistic that the Iranian government would approve the releases, noting a pattern of increasing repression during times of crisis.

For Reza Younesi, whose 25-year-old brother Ali Younesi has been held in Evin prison since 2020, conditions have already got worse. On Wednesday, his family received news that Ali had been moved from Evin to an unknown location and that attempts by lawyers to locate him had proved fruitless.

“His cellmates called my mum from prison to let us know. We were hoping that maybe he’s moved to another ward or even another prison, but there is no information,” said 43-year-old Younesi, speaking from Sweden.

He added that he feared his brother was transferred to ward 209, where interrogations are conducted. According to a 2020 Amnesty report, security forces have beendocumentedtorturing detainees in ward 209, including through beatings and electric shocks.

Ali, a student activist, was accused of possessing “explosive devices” by Iranian authorities and of being associated with the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran, which Iran considers a terrorist group. He was initially sentenced to 16 years in prison, which was reduced to six years and eight months on a recent appeal.

“This is a pattern for the regime. What they do when they are in crisis to show that they can control society is to become more aggressive, they suppress regular people in society, especially prisoners,” Younesi said.

Human rights groups shared Younesi’s concern. The New York-based Center for Human Rights in Iran warned on Thursday that 54 political prisoners on death row were at grave risk.

“There is growing fear that Iranian authorities may use the cover of war to carry out these executions, using them as tools of reprisal and intimidation to further silence dissent and instil fear across the population,” the rights group said in a statement.

Last Saturday, security forces arrested at least 16 people for “spreading rumours” and residents in Iran told the Guardian they had noticed an uptick of arrests of people critical of the regime. Iran’s interior ministry has published a video of someone confessing to working on behalf of the Mossad (Israel’s intelligence service) in Iran.

Families of political prisoners say Israeli airstrikes on prisons are not the answer to state repression. They say bombing prisons could put political prisoners at risk.

“We don’t believe he [Najafi] is safe at all – we know both the brutality of the Islamic Republic and the intensity of Israel’s strikes. When he calls us, we can hear the sound of missile launches and anti-aircraft through the phone,” Hussein said.

Inside Evin prison, detainees have reportedly started to stock up on goods, fearful that the fighting outside will lead to deterioration of conditions. Ali’s cellmates were buying more food from the commissary, Reza said.

Checking on loved ones inside prisons has become more difficult as Iran’s government has imposed a near-complete internet blackout on its population.

Mehraveh, used to speaking to her father from abroad by calling her mother who would put him on speaker on a separate phone, has been unable to hear his voice since the bombing of the prison.

For Reza, whose family has not heard from his brother in six days, the lack of communication was deeply worrying.

Before, Ali would call his mother every day on the prison phone, comforting her with the mundane details of his daily routine. He had recently begun learning French from other prisoners, and was teaching them astronomy – his passion – in return.

“I always tell him that he needs to do sports to make sure his body is not degrading,” Reza said. “He always says, yeah don’t worry, I’m doing it … Now we have no information from him, it’s a very stressful time.”