InLocked Down, a song by the San Diego-based poet and rapper, Chance, she sings with both foreboding and care: “Every day that you wake up you’re blessed / love every breath, ’cause you don’t know what’s next.” Chance wrote the song – originally a poem, its title a callback to Akon’s Locked Up – while imprisoned in Phoenix, Arizona, during the beginning of the Covid pandemic and subsequent lockdown (“six feet apart in a five-by-five,” she raps in the same song, alluding to the virtual impossibility of social distancing in the American prison system). It’s part of Chance’s self-published collection of short stories and poems, entitled Pandemic Soup for the Soul, a reflection on “what we experienced during the pandemic crisis”, she shared with me in a recent phone call. “It’s crazy how they maintained control and instilled fear within us. When you’re locked up, you ask yourself … are you going to be angry, or are you going to find what your calling and purpose is?”

Locked Down is also one of 16 tracks onBending the Bars, a hip-hop album featuring original songs by artists formerly or currently incarcerated in Florida’s Broward county jails (with the exception of Chance, a Florida native). Bending the Bars was organized by the south Florida abolitionist organizationChip– the Community Hotline for Incarcerated People – which was initially founded to support inmates during the early days of Covid. Nicole Morse, a Chip co-founder and associate professor at the University of Maryland, says the organization began fielding calls in April 2020, primarily from Broward, the county just north of Miami-Dade; the calls were primarily about medical neglect, abuse and an atmosphere of abject fear, perpetuated by guards who demanded silence.

It’s no secret that the prison-industrial complex is inherently abusive, especially Florida’s, which has one of thehighest incarceration rates per capita. As Morse explained in an interview, “Most jails and prisons have an element of violence, retaliation, coercion – it’s what the system relies on to control people.” And Broward county is uniquely punitive: “Broward county jails are standouts in how lawless they seem to be, how much the corrections officers are authorized to act without any oversight.” Last year, it wasreportedthat 21 inmates had died in Broward jails since 2021,prompting the NAACPto declare the need for an investigation. In 2021, the data Chip had gathered was used to support a lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union of Florida and Disability Rights Florida on behalf of individuals suffering from Covid in the Broward county jail.

Something more hopeful was emerging from those hotline calls, too: creativity. “People wanted to share their latest poetry or a song they were developing,” Morse said. “Art was helping people survive an incredibly desperate time.” Noam Brown, a children’s musician and Chip committee member, began dreaming up the idea of an album; Morse, whose research looks at LGBTQ+ cultural production, particularly collaborative media production with incarcerated artists, co-signed the project. They wanted to do more than simply raise awareness. “When you look at how raising awareness functions politically, people who are not impacted by the system tend to get overwhelmed and apathetic, because the system is so violent,” Morse said. Instead, Chip hoped to create a platform for the wealth of talent they continually encountered. The organization began fundraising, applying for grants and putting the word out that they were producing an album; Gary Field, an incarcerated organizer, writer and scholar, became the executive producer, helping to connect the artists with Chip.

Musicians on the inside used two phones to record their songs – one as the microphone to record their vocals, the other to listen to the beat. “The challenges were phenomenal,” Field shared in a phone call. “People couldn’t even talk to their families, never mind collaborate on something as complicated as producing a studio album. We were in the middle of a pandemic. There were four phones and 40 inmates trying to use them.” Spaces with two easily accessible phones were limited; the duration of any prison phone call is restricted. But Chip covered the costs of the calls, while Brown’s brother, Eitan, worked as the sound engineer, and the Grammy-winning children’s artists Alphabet Rockets helped create beats. Artists who were already out were able to spend time in the studio, including Chance, who returned to southFloridaafter her release. After reconnecting with a former classmate, the two attended a meeting for Chainless Change, a Lauderhill-based non-profit advocating for those affected by the criminal legal system. “It was divine – I don’t believe in accidents; I knew I was being called to go back to Florida,” Chance said. She began working with the group and helped organize a poetry event, where she met Field, Brown and Morse. She asked if they had room on the album for one more.

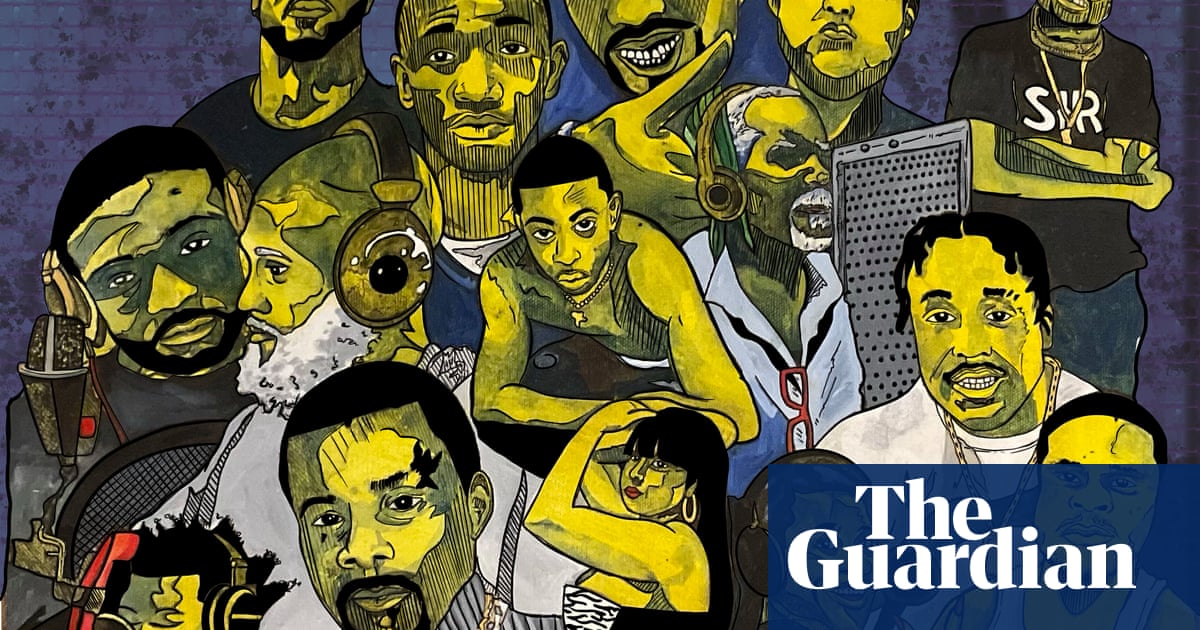

The result is nearly an hour of uniquely south Floridian hip-hop and R&B, both of which are constellations of so many genres – Caribbean beats, southern bass, Deep City soul, Miami drill – poetic musings on love, loneliness and hope, and demands for systemic change to the draconian and brutal conditions of the Florida prison system. While Morse noted that the album’s sound quality was impaired by technical limitations, Bending the Bars is polished and clear, an accomplishment owed partly to its production and mostly to the ingenuity of its artists: singers, rappers and collaborators like J4, dangeRush and Chuckie Lee, all of whom alchemized the tracklist into a textural tapestry: playful, mournful, educational and intentionally dotted with prerecorded interjections from the prison phone line (“you have one minute remaining”). Field, whose song Tearing Down Walls and Building Bridges closes the album, studied theology at Columbia University and received his master’s from Gulf Coast Bible College, and has contributed 2,000 pages of writing to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology civic media project Between the Bars. He knows, intimately, the significance of the writing process. “I remember, as an inmate back in 2010, what a profound sense of gratitude the opportunity to write gave me,” he shared. “The relationship between writing, rap, hip-hop, music, jails, prison – it’s really intertwined.”

County jails, Field added, are incubators for hip-hop, especially in Broward county, which cultivated “legends like Kodak Black and YNW Melly … but the diversity of voices on Bending the Bars is a natural extension of the eclectic mix of detainees that can be found in almost any urban jail”. Field added that space for writing, and a deeper understanding of philosophical ideology, are inevitable on the inside. “While on an academic level, philosophy can be broken down into many categories – ontology, epistemology, ethics, morality – in its simplest sense, philosophy is man’s attempt to figure out the world around him and his place in it,” he said. “When that world is reduced to what lies behind the razor wire, an old-timer who has served 35 years … can provide more wisdom than someone with a PhD in metaphysics.”

The system often censored mail or blocked phone calls during the recording process; Morse said that this necessitated new pathways for the collaborators to connect with each other. “We had to develop a set of strategies to overcome those barriers,” they said. “The project was made without the cooperation of any prison or jail. Every strategy we came up with for how to get through to people, how to connect with them, how to find them if they seem to have disappeared in the system – we can now share those strategies with loved ones of incarcerated folks who don’t have any additional privileged access.” It’s for this reason that Chip hopes the album will serve as a model for ways of interacting with and caring for those inside the system – and for future creative endeavors. “Gary always says there’s thousands of jails in the country, and in each one, there are folks who have as much talent as the people we connected to,” Morse added. “We did this independently and autonomously. We hope this inspires others.” In 2026, Chip will release a documentary about the process.

After our call, which was cut off due to time restrictions, Field sent an email describing the prison-industrial complex as “an insidious and intentional campaign” that, he warned, is an ongoing harbinger of societal abuse, regardless of a person’s criminal background. “If allowed to continue unchecked, it will not be content with feeding upon the poor, minorities, those suffering from substance abuse issues and undocumented immigrants. How long until the weaponization of the justice department begins to target journalists, educators, scientists, researchers, protesters and even some politicians as enemies of the people? The time to recognize, organize and speak out is now.” It’s a point he illustrates in his song: “Well, they’ve criminalized mental illness and treat addiction as a crime / How long do you think this moves from the shadows to prime time? / … Won’t you raise your voice / Help someone to stand up / Silence is a choice.”

Bending the Bars is released on 11 June