Iremember two things about the first full week of January 1972. I passed my driving test on the Monday, and on the Friday I made my weekly trip to the library and borrowed The Day of the Jackal byFrederick Forsyth. I had no idea I would one day be a writer myself – at that point I was merely an insatiable reader – but in retrospect that Friday marked an important way station on the journey from one to the other.

I gobbled up the book and thought it was fantastic – fast, pacy, exciting, suspenseful and laced with detail and intrigue. Then I thought, wait, what? How was this book working? It was a twin-track thriller – an assassin hunts his target while law enforcement hunts the assassin. But the intended victim was Charles de Gaulle, a real person, the president of France, who had died from ananeurysmin 1970. Therefore we all knew the assassin had failed. How did that not short-circuit the will-he-won’t-he suspense that thrillers seemed to require?

And the main character was an absolute cipher – a completely blank slate. No backstory, no history, no explanation, no reason, no justification. No description. Not even a name. Yet we all rooted for him. We secretly admired him. We wanted him to succeed.

How-to books about writing tell us to create sympathetic, fleshed-out characters, and then place them in great peril, and leave the outcome uncertain until the last page. Forsyth ignored all that. In so doing, he showed us that thehowquestion was as powerful as the who, why, where and when. He showed us that intriguing detail and inside information was compelling in itself. He created a year-zero thriller that reset the whole genre.

Sign up toBookmarks

Discover new books and learn more about your favourite authors with our expert reviews, interviews and news stories. Literary delights delivered direct to you

after newsletter promotion

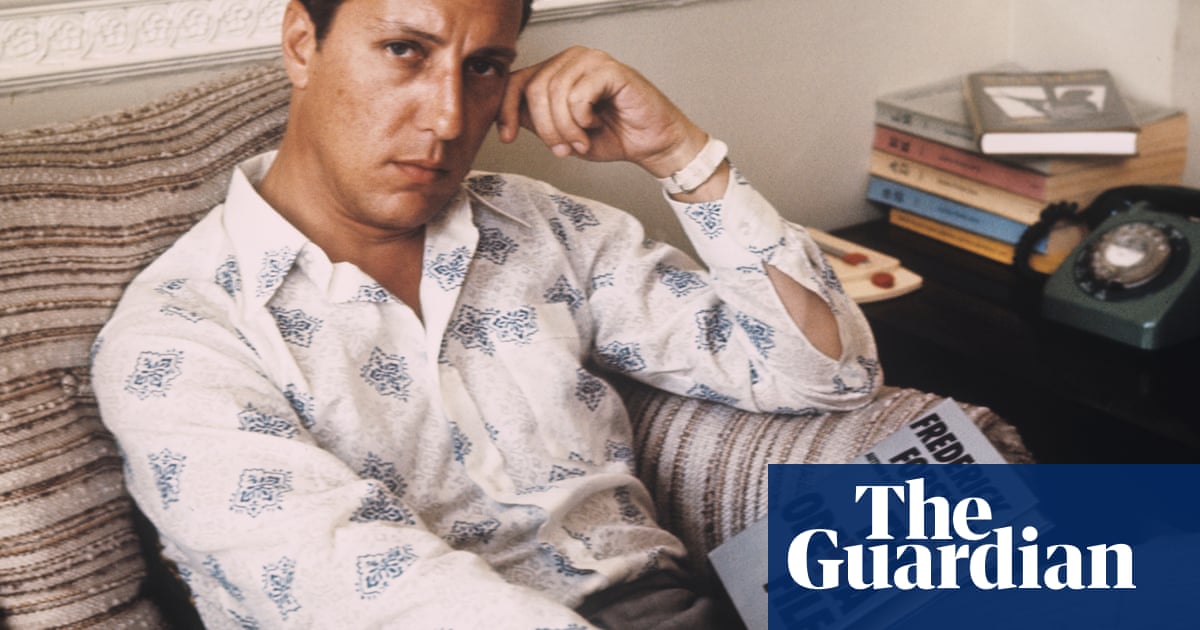

Inadvertently, he claimed. I met him in the early 2010s and we began hanging out occasionally and corresponding fairly often – he by typed snail-mail, me by email printed for him by his wife. He said he knew he had to write the book because he was unemployed and broke, but at first he had trouble feeling his way into it. He was a journalist by trade, and his lightbulb moment was to imagine he was doing a book-length true-crime feature about recent events. The result was a novel that changed the rules for all of us that came after.