9 June 1973

At the end of most journalistic rainbows stands Freddie Forsyth, hugging a large pot of gold. A pot spilling over almost without effort. It’s a remarkable tale; one which (apart from confirming that there is a Father Christmas) tells you a lot about modern publishing and the demise of hoary, leather-bound gents making genteel fortunes between trips to the Reform Club.

Operatively our story begins in January 1970. Forsyth, ex-Eastern Daily Press cub reporter, ex-RAF pilot, ex-Reuter man in Paris and Berlin, acrimonious ex-BBC correspondent inBiafra, was also becoming an ex-freelance. No commissions, dwindling cash. Thus, wanting other employment, he finally sat down in a series of hotel rooms and – through 35 days flat – wrote a thriller idly planned seven years before on the French reporting stint.

It was called The Day of the Jackal, about a plot to kill de Gaulle. His agent sent it, with diminishing fervour, to four publishers who (perhaps because they were asleep) expressed polite disinterest. By August, Forsyth was getting despondent; as a last throw, he dispatched the manuscript to a French firm. They wrote back enthusiastically. He then sent that letter to Hutchinson, who asked for the book on Friday; on Monday he had a fat three-novel contract. Foreign editions of the Jackal now fill Forsyth’s mantelpiece. Over five years it will make him a conservative £250,000.

One throw, but not the last. A Jackal film, directed by Fred Zinnemann opens in London next week (after ecstatic American reviews). Novel two, The Odessa File, is an even bigger world bestseller, and will top another quarter-million with thousands to spare. Novel three, The Dogs of War, lies a chapter or so from completion, poised for a fresh killing next spring. Unless he casts his royalties to the winds, Forsyth, at 34, is rich for life after, perhaps, 100 days solid typing.

And that, astonishingly enough, is precisely where he’ll leave it. Three books and no more. The end of the rainbow. What comes next? Perhaps a little scriptwriting. Maybe some magazine reporting. Holidays at a newly purchased Spanish farmhouse. “I’ve always been a loner.” So back to a lone, freelance, journalistic role using the name to get plum assignments and not caring a fig for cash attached because it’s pleasantly irrelevant.

Are the books, in any literary sense, good? Not very. Forsyth admits he writes them the way he does because that’s the only way he can write. Straight narrative, packed with voluminous and sometimes excruciating technical detail (all meticulously researched, which is the true grind). Rather like reading, a 350-page Sunday Times Insight grope. The plotting – which is where he starts – often seems ropy (Odessa ends with a confrontation so stagey that Holmes and Moriarty, wrestling on the brink of the Reichenbach Falls, might pause and blush at the thought of it). Soggy globules of reportage verite litter and throttle action (our Nazi-chasing Odessa here goes to see Lord Russell of Liverpool amongst his rambling roses, just as Forsyth plus notebook did). Sometimes you feel nobody’s read the typescript through before it sped to lucrative presses. There are few intricacies, no proper twists or subtleties.

And yet, however crude or cumbersome, both (especially Jackal) are surprisingly effective. They exude a naive zest: coatings of detail, poured like thick chocolate sauce over a mingy scoop of vanilla ice, distract attention, criticism, distrust. Perhaps because he’s never read Eric Ambler orGavin Lyallor any of the other masters of the British thriller in any coordinated way, Forsyth is a true primitive, contributing something different and hugely marketable to a defined genre.

His method takes a situation and location he knows intimately (by living and breathing it for months and years rather than a fortnight’s impecunious research trip) then fitting a yarn to that morass of background. All the gossip, all the briefings he absorbed at the time and couldn’t quite print. A few characters are fiction; most are lightly spiced fact. In the wake of Jackal, the French government held a small inquiry to find out who’d leaked their secret service structures.

Of itself, this method explains best why he’s quitting. The Dogs of War is about an African coup, an African mess (like Biafra), mercenaries, and big European businesses who pull the bloody strings. The Jackal was France, Odessa, Germany – Dogs, Biafra. That exhausts Forsyth’s three spells of foreign experience. Unless he wrote a thriller about newspaper work in King’s Lynn, he’s finished. The only way of recharging would be to disappear in, say, South America for a couple of years – and even then he’d probably need a mainstream job providing a haphazard spray of facts and insights, piles of fuel to spark an idea.

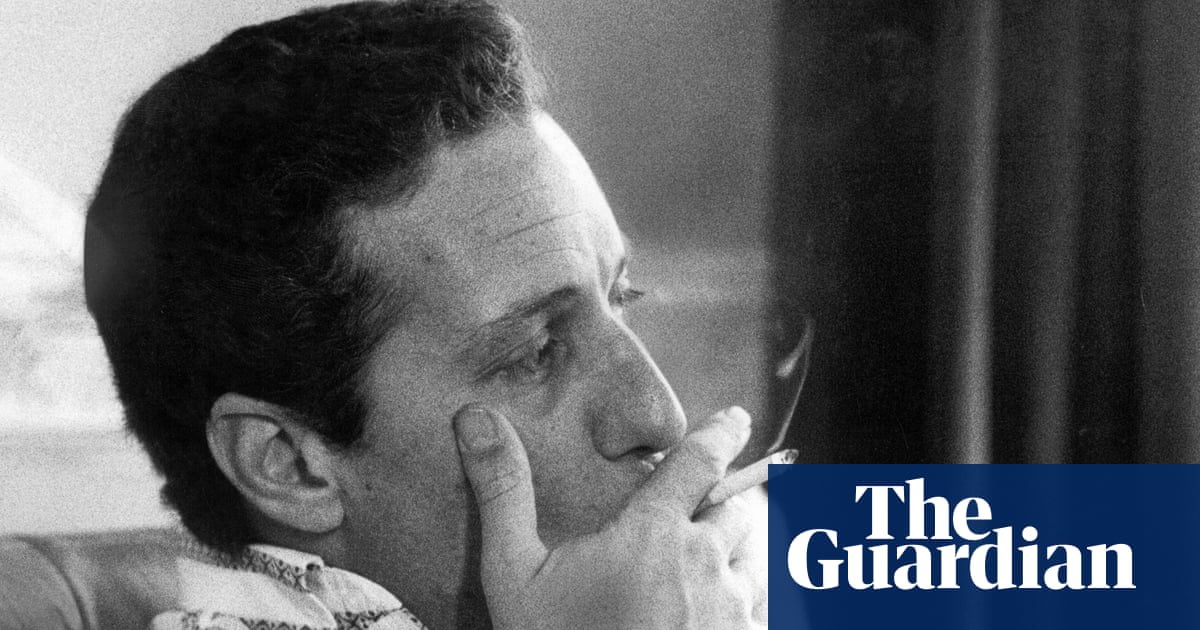

It all seems deceptively simple. You sit in his small flat over a dentist’s surgery near Regent’s Park and imbibe an everyday tale of gold-minting life. Forsyth isn’t a Fleming exotic. His dad sold furs in Ashford, Kent. He doesn’t care much for publicity bandwagons or cocktail promotions. His Foyles’ literary lunch speech set brevity records. The car outside is unchanged by success. He likes jeans, Pernod, an occasional night at Tramps. His girlfriend rings to announce she’s got flu. Frederick hunts for some aspirin to take round.

A fluent, unflamboyant fellow. Not much interested in home politics. Loathes dictators (and blushes when you raise the Spanish farmhouse). Exposé journalism is what he cares about most; he had a high old time in France last year digging round the drug scene for a colour supplement and causing consternation among the Marseille connections. “That was a 20,000 word spiel that caught a few people below the belt. It was nice, you know, to take a trip round the airfield again and not worry about money. I just let my agent negotiate the bread and got on with it.”

Talk reporting and he comes alive. The mechanics of writing – 10 pages a day from eight to 12 in the morning make a 300-page book in 30 days flat – and it’s mere iron discipline. Talk events for keener reaction. “I mean, take Lonhro. If you’d written a novel using those facts last year everybody would have said come on, this is a bit bloody melodramatic. Do it in five years and they’ll say: this was how it was.”

The method, in short, won’t be buried with Biafra. Nor can one quite see Forsyth vegetating for ever amid sun and cheap booze. He’s like no other novelist because the business of novel-writing clearly interests him hardly at all; the business of bizarre, digging, living eclipses all else. He’s not an author but a recognisable Fleet Street type – there are at least two on the Guardian – phlegmatically fearless, inquisitive, pragmatic, a bit solitary. “A loner,” he says again. At a guess, I’d think there may be more thrillers five years or so hence, when there’s more experience; but as things stand, The Dogs of War will end a weird interlude and Freddie will drift away into the wide, blue, perilous beyond – leaving behind a predictable cluster of imitators, an agent rolling in bread, and four exceedingly chagrined publishers. “So the name fades. So what?”