It only took 10 minutes for the trio of eighth-grade girls to recount the life story of Carol Ruckdeschel, the alligator-wrestling environmental activist sometimes called the “Jane Goodall of sea turtles”.

Inside the student union at the University of Maryland, about a 20-minute drive from Washington DC, and armed with papier-mache reptiles, they embarked on a performance that included a litany of costume changes and a pony-tailed rendition of the late president Jimmy Carter, an ally of the 83-year-old Ruckdeschel’s work.

When it concluded, the scary part began. A panel of judges peppered the girls with questions.

Why did some people consider Ruckdeschel to becontroversial?

The girls hesitated. “Sorry,” said one, “but what does that word mean?”

It was the first day of NationalHistoryDay (NHD). In its 51st year, the annual US-based competition invites the top middle and high school students from more than half a million competitors to present their projects: documentaries, performances, websites, papers and exhibits on any topic from history, as long it adheres to the year’s theme. The winners get cash prizes and the admiration of their teenage peers.

The students come from all over – places like Oregon, Indonesia, North Dakota, Guam, Arkansas and China. Jake Sullivan, President Joe Biden’s national security adviser, competed more than 20 years ago, as did Guy Fieri, whose project on the soft pretzel’s origin helped inspire a future career as a TV star restaurateur.

I also competed in NHD, reaching the Florida state competition in 2007 and 2009 with my twin brother. As I reported this year, I joked with students that I’d finally made it to nationals, just 16 years too late. Hardly any of them were even alive then, and the national reality couldn’t have changed more.

In April, NHD lost $336,000 after the Trump administration and the “department of government efficiency” slashed funding for the National Endowment of Humanities, putting NHD in jeopardy.

“We had so many messages from kids saying, ‘Please, please, please we can’t let History Day go down,’” said Cathy Gorn, NHD executive director since 1995 and “the Taylor Swift of history”, as one student dubbed her last year (to many, there is no greater compliment). On social media she made an impassioned plea for donations. Last-ditch fundraising followed, including contributions from students, like a group from New York that held a bake sale and sent Gorn more than $300 in proceeds.

With that, the competition found new legs – for this year, at least. “It’s kids learning,” said Gorn, “what is controversial about that?” And these students want to learn the full history – both its roses and its thorns, or what Alexis de Tocqueville called “reflective patriotism”.

“They have no filter,” John Taylor, the NHD state-coordinator from Maine, told me. “They’ll call anyone and ask them anything.”

When I competed, the cardinal rule was to abstain from any citing of Wikipedia, a transgression that today seems nostalgically benign. Students now learn to hunt down reputable sources in an era defined by untrustworthy generative AI and revisionist histories. Some students even found that sources they’d cited in their research this spring – from governmental websites, no less – had disappeared altogether.

“You start to realize that many of them do more research for NHD than you did for your master’s thesis,” Taylor laughed. He told me about a 130-page bibliography a student once turned in: “That thing could have taken down a woodland creature.”

These are history-defining times. Do students at NHD see the parallels, the precedence, in their projects? “Oh yeah,” said Gorn, “they get it.”

The scene from the student union last Monday could have come straight from a Where’s Waldo book. In one corner, a life-size cutout of George Washington leaned against a wall, until it was scooped up by girls in colonial-era ballgowns. Four lanky boys huddled together, their traffic-cone-orange dress shirts illuminated in the morning light. I heard a boy reading through a script, his manufactured accent undulating between George Clooney in O Brother, Where Art Thou? and wild west cowboy.

In another hallway, lanyarded coordinators carried folders full of research papers and flash drives loaded with digital backups of student-directed documentaries (after a snafu at the state level, one group told me they’d brought eight). Nervous students were tailed by teachers and nervous parents with little brothers and sisters in tow, just happy to be along for the ride.

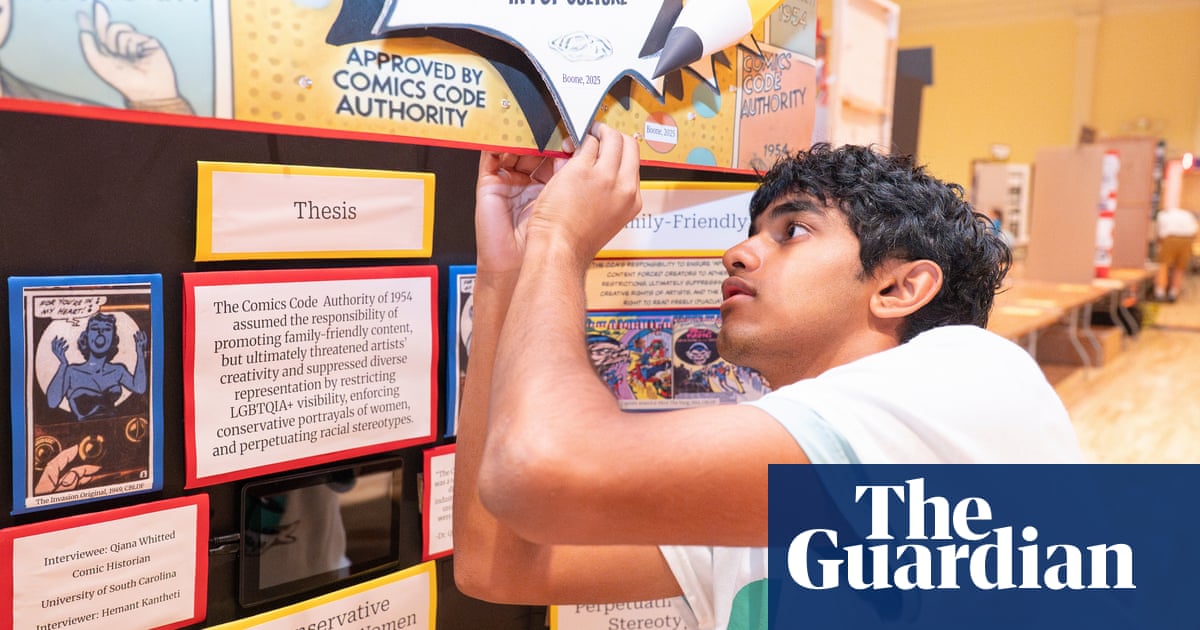

As I walked in and out of competition rooms over the next three days, I saw a spectrum of stories that spoke to this year’s competition theme, “Rights and Responsibilities” – the Elgin marbles, birthright citizenship, lobotomies, Martin Luther King Jr, social security, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, the first Black character to appear in Charlie Brown. The theme, which sought to magnify the relationship between individuals and society, seemed especially prescient, even though it is one of several that NHD has recycled over the years.

At a table finishing up a meal from Chick-fil-A sat Chloe Montgomery, an eighth-grader from Indiana, with her father, Ryan. The topic she chose to research – the Salem witch trials – had been bubbling up for years. “You grow up hearing about the trials a lot,” said Chloe, “like in Hocus Pocus!”

Her project had ascended from the local competition in her hometown of Mishawaka, through regionals and states, all the way to nationals. Now, father and daughter were in the US capital for the very first time. She, too, was impressed by the spectrum of project topics: “I saw one about Green Day!”

In the hallway after the performance about Ruckdeschel, I caught up with the eighth-grade trio. “We’ve had hundreds of sleepovers to work on this!” said Zoe Otis. Not only that, they’d traveled from their homes in Knoxville, Tennessee, ferried from mainland Georgia and then biked about 35 miles roundtrip – “half of that was in the dark!” – to meet Ruckdeschel on Cumberland Island, where she lives alone in a cabin.

They’d spoken with the octogenarian recluse, who still keeps a research lab with jars of turtle guts and bugs. For the girls, it was an eye-opening experience that at times bordered on gut-wrenching. “There was a giant, dead boar on the side of her house,” said Gemma Walker. “She hunts, and eats roadkill.”

“We always tell ourselves to ‘embrace the cringe’,” said Addy Aycocke, laughing. This, it turned out, was part of the reason Ruckdeschel was considered controversial, along with her decades-long jousting with the National Park Service and the Carnegie family over environmental protection of the island and its sea turtles.

It’s this flavor of research – active, firsthand, hands-dirtying – that history professors at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio, who started NHD in 1974, saw as the antidote to the traditional textbooks and multiple choice repetition that often went hand in hand with learning history. A science-fair-like competition, they hoped, would propel students to both dig into dusty archives and track down primary accounts – to feel history, rather than to memorize it.

Later on, I heard stray conversation aboutTrump’s deploymentof the national guard and marines in Los Angeles. Less than 10 miles away, tanks were arriving in Washington for amilitary parade. “You look at the news, and all you see is negativity,” Gorn told a room of volunteer judges. “But spend a couple of days at National History Day and it’ll give you hope.”

It was true. There was an attitude of genuine, mutual encouragement that seems difficult to come by these days. The students seem to understand that nothing is a zero-sum game, that striving for excellence and being amiable with competitors are not mutually exclusive.

When I spoke to Gorn a week before, we’d discussed the critical role of history, and its sometimes precarious place in school curriculum.

“No Child Left Behind left history education behind,” she said of the 2001 congressional act that, in a quest for equality and accountability in schools, shifted focus to standardized testing and left less time for the humanities. Meanwhile, the national emphasis on Stem subjects could be traced to the National Defense Education Act that followed the Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik in 1957. These subjects are important – she doesn’t argue that – but “not at the expense of history”.

“It’s a real disservice to our democracy,” said Colleen Shogan, who works with NHD and was archivist of the United States until February, when she was dismissed by Trump without reason. “We are not teaching kids how the constitution functions and what the principles are that we all agree upon as Americans.”

The politicized situations that some history teachers find themselves facing are a marked difference from when Gorn began in education in the 1980s. Disgruntled parents and school boards sometimes seek repercussions if lessons don’t align with their own interpretations of history, often along the lines of race and equity. “I’ve heard many [teachers] say, ‘If I can’t teach complete history, I can’t teach any more,” Gorn said.

Not only that, she lamented the attitude that learning the thorny parts of the nation’s past is somehow teaching kids “to hate America”. Not true, she said. “Kids are resilient and they know when you’re pulling it over their eyes.” Young people need to understand that there has been struggle. “That’s how we develop empathy,” she said. “Learning history does that.”

It was 6.58pm on Monday, and a crowd had gathered around flat screens throughout the student center. In a few minutes, they’d display the list of competition finalists. Students were anxious. Some killed time by doing each other’s hair.

At 7pm, several shrieks sounded. A little brother covered his ears and mouthed “Oww!” while student faces split into a telling binary of smiles and frowns. Teachers and parents – quite a respectful bunch when compared to the kind you might find on a suburban soccer field – squinted to read the tiny font. “Maybe that judge wasn’t so bad after all,” said one mother.

Three of the smiling students were from Minnesota. Sara Rosenthal and Helen Collins had been selected to move on for theirdocumentary about Radio Free Europe, the American soft-power station begun during the cold war to spread democratic influence to communist countries. Their friend, Jack Grauman, was also advancing. For months, he’d researched Frank Kameny for his one-person performance about the astronomer who’d been removed from the US army in 1957 for being gay.

It was “powerful” to be headed to the finals, Grauman said, and just miles away from Washington, no less, where the current administration is targeting LGBTQ+ rights. Meanwhile, funding for Radio Free Europe is on the Dogechopping block, as are press freedoms around the world. Their teacher told me the girls had to update the ending of their documentary several times to keep up.

Even here, students and educators sometimes hesitated before answering my questions. One group of students, from Singapore, was talkative until I asked about their projects’ relevance to today – one was specifically about American borders. In my periphery, I saw their classmates miming the slit-throat gesture, as if to say “don’t answer that one”.

Later, I spoke with a group of judges inside the forest of elaborate poster board presentations. One of them kindly declined to go on the record: “I’m a federal worker. I don’t want any attention.”

Back with the Minnesotans, the outlook was rosy. How would they be celebrating? “We’re going to the dance!”

Before leaving campus for the evening, I poked my head into what I’d expected to be an awkward affair. Bass of early 2000s hits – oldies to this crowd – pounded through the walls. I passed two middle-schoolers outside.

“It’s weird to talk about your exes to your new boyfriend, you know?”“But I want to know everything!”

Inside, hundreds of students were cherishing their success or drowning their relative disappointment with fruit juices and soda. It was a mocktail of hoodies, high heels, recycled homecoming dresses, black-suited vests, and one especially-civic-minded student in a T-shirt that said “Support Local Music”.

The trading of pins – each state or country delegation had brought their own – provided much of the necessary social lubrication.

And then it was Thursday: results day. Across the hardwood of an indoor arena, delegations marched in like at an Olympic closing ceremony, some carrying flags and inflatable animals and wearing bedazzled top-hats.

Once everyone took their seats, Gorn stepped up to the microphone, pumped her hands in the air and roared: “Happy History Day everybody!” Then she teed up a special treat: a congratulatory video from a real-life Thunderbird pilot and NHD alum.

Finally, it was time to hear the results. It was a successful day for the Minnesotan contingent. Grauman won a special prize for “equality in history”, climbing the steps to the stage wearing a large smile and a pair of Crocs. Almost two hours of nervous waiting later, Rosenthal and Collins heard their names announced at last – the silver for middle school documentary was theirs. The gold went to a pair of students from Chiang Mai, Thailand, for their look into theUK miners’ strike of 1984.

If funding comes through, next year’s NHD theme – “Revolution, Reaction, Reform in History” – will again seem especially relevant. If there was a silver lining to the uncertainty, Gorn said, it’s that students felt how a decision made far away in the nation’s capital could directly affect them.

As Vritti Udasi, a high schooler from Florida, told me: “The place where we are today didn’t come out of thin air. If we study history, dissect it, then we can progress.”