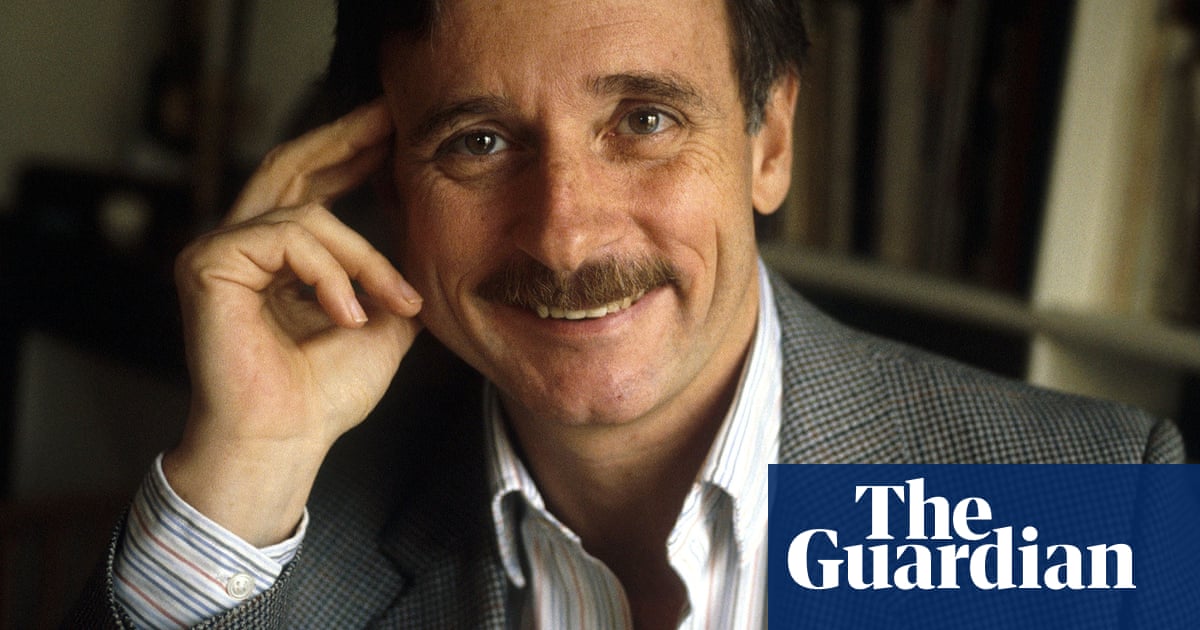

Alan Hollinghurst

Edmund White’s luminous career was in part a matter of often dark history: he lived through it all. He was a gay teenager in an age of repression, self-hatred and anxious longing for a “cure”; he was a young man in the heyday of gay liberation, and the libidinous free-for-all of 1970s New York; he was a witness to the terrifying destruction of the gay world in the Aids epidemic in the 1980s and 90s. All these things he wrote about, in a long-term commitment to autofiction – a narrative adventure he embarked on with no knowledge of where or when the story would end. He is often called a chronicler of these extraordinary epochs, but he was something much more than that, an artist with an utterly distinctive sensibility, humorous, elegant, avidly international. You read him not just for the unsparing account of sexual life but for the thrill of his richly cultured mind and his astonishingly observant eye.

What amazed me about A Boy’s Own Story, when it came out in 1982, was that a stark new candour about sexual experience should be conveyed with such gorgeous luxuriance of style, such richness of metaphor and allusion. This new genre, gay fiction, could also be high art, and almost at once a worldwide bestseller! It was an amazing moment, which would be liberating for generations of queer writers who followed. These younger writers Edmund himself followed and fostered with unusual generosity – I feel my whole career as a novelist has been sustained by his example and encouragement. In novels and peerless memoirs right up to the last year of his life he kept telling the truth about what he had done and thought and felt – he was a matchless explorer of the painful comedy of ageing and failing physically while the libido stayed insatiably strong. It’s hard to take in that this magnificent experiment has now come to a close.

Colm Tóibín

Edmund White wrote with style; he cared about style; he made it seem natural and effortless. He wrote and indeed spoke with a kind of delightful candour. He loved revelation and gossip and intrigue. The idea that everyone he knew had secrets fascinated him. He chuckled a lot. He read all the latest French novels. He saw no reason why he should keep things to himself and, because he was gay in a time when gay life had not appeared much in fiction, that became one of his great subjects.

A Boy’s Own Story, which came out in 1982, had enormous influence. It was an essential book for several generations of gay men. In The Beautiful Room Is Empty and The Farewell Symphony, White charted the changes and the tragedies of the gay life that had seemed so promising in A Boy’s Own Story.

In writing about gay characters, White also became one of the chroniclers of city life, especially New York and Paris. (During a brief stay in Princeton, he suggested that the only relief from tedium was to howl nightly at the moon.) White was in full possession of a prose style that was deceptive in how it functioned. His writing could feel like conversation or someone thinking clearly and honestly or taking you slowly into his confidence. The cadences were close to the rhythms of speaking, but there was also a mannered tone buried in the phrasing, which moved the diction to a level above the casual and the conversational.

The book of his that I love most is his 2000 novelThe Married Man, which is a kind of retelling of Henry James’s The Ambassadors. White dramatises with considerable subtlety the conflict between the idea that the personal is political (“which,” White wrote in 2002, “may be America’s most salient contribution to the armamentarium of progressive politics”) and the legacy of Vichy France filled with secrecy and ambiguity and the ability to live several compartmentalised lives.

In the recent years, White’s apartment in Chelsea, shared with his husband, the writer Michael Carroll, was a centre of fun and laughter, a place where you got all the latest news. Books were piled up. They, too, were treated as kind of news. He worked every day, writing at the dining-room table. He made light of his illness. He was, in many essential ways, a lesson to us all.

Adam Mars-Jones

I met Ed White in London in 1983, at the time of the UK publication of A Boy’s Own Story. I had reviewed the novel for Gay News, and he knew that my verdict was unfavourable but not what my objection was (I described it as a cake that had been iced but not baked). This didn’t deter him from making a conquest of some sort – a degree of resistance could positively inflame his charm. We took a stroll round Covent Garden. I bought him a punnet of whitecurrants, a fruit with which he was unfamiliar, though feigning ignorance in order to please me would have been perfectly in character. He must have registered my lack of carnal interest but went on sexualising our promenade, asking me if one bystander was my type, telling me that another had given me the eye.

To have become his friend without even a moment of sexual closeness was, a least at that time in the New York gay world, an anomaly and perhaps even a distinction. I visited Ed several times in Paris, sleeping on the daybed in his enviable flat on the Île Saint-Louis. In the morning he would help his ex-lover John Purcell get ready for a day of graduate study, a routine – as he was well aware – with overtones of a mother packing her son off to school. We would have one more cup of coffee and listen to some chamber music, Poulenc a favourite. Then he would say, “I must get back to thedarlingnovel” (he was working on Caracole at the time), and lie on his bed to write in longhand. I loved those visits, and some of that was down to Paris, but most to his hospitality. For a night in he might buy rabbit loin in mustard sauce pre-prepared from atraîteur,unthinkable sophistication. It was from him I learned that “cutting the nose off the brie” was not just bad manners, as I hadn’t known, but a named crime.

He was writing a monthly column for American Vogue, so socialising was a job requirement as well as a pleasure. Even so, I was mildly scandalised that his French literary friends took it for granted that he would pick up the tab in restaurants. Priggishly I would treat him to a meal now and then, though I think he took more pleasure in largesse than in the presumption of equality.

Olivia Laing

I saw Edmund White on the A train once, like glimpsing an emperor in the grocery shop. I must have been barely in my teens when I first read A Boy’s Own Story, the Picador paperback with the brooding boy in a purple vest on the cover. I was seduced by everything: the lovely, supple, almost shimmering language, the explicit precision applied to sex and class. Cornholing, a word I’d never heard before. Above all, it held out an invitation. It was from White that I realised a writer takes the rough material life gives – unwanted, shabby, maybe repellent – and makes it their own by way of sensibility and style, that alchemical translation.

Years later, I met him. He was at an adjoining table when my first American editor took me out for lunch. He was celebrating too, toasting the publication of Justin Spring’s Secret Historian, a book about the unconventional sexual researcher Samuel Steward. It was pure White territory: sex explored exactly and without shame. His presence that day felt like a blessing. He interwove the elegant and the explicit, he expanded the bounds of what could be written about and also how a life could be lived. There is a generation of writers you write for without quite realising it. They set the bar, and then they go. That beautiful room is emptier now.

Mendez

Edmund White was one of those writers whose work was as fresh and immediate as gay bar gossip, but from a place of deeper learning and knowledge. I met him once in 2019, over dinner with Alan Hollinghurst in New York, and he remained every bit as witty and sex-positive as I’d found him in his books. The incredible thing about him is that he was one of very few gay writers to remember the pre-Aids era and survive into old age. When I think of White I think of the bathhouses of 1970s New York City and his conspiratorial storytelling, though that’s not to undersell him as a prose stylist. Such was his keenness to connect with a gay-literate rather than a mainstream, almost anthropologically minded audience, that The Joy of Gay Sex, which he co-wrote, retains a contraband feel to this day.

Tom Crewe

Edmund White was not a gateway to gay literature, or to the gay experience, since that would imply that he was not in himself a main destination. However, he was very often the man who opened the door to the expectant reader, who took them by the elbow, led them inside and eagerly showed them everything that was going on – that wasreallygoing on. There are his novels and his memoirs, of course, with their brave, bracing, dirty and dignifying candour, and his biographies, of Genet,Proust,Rimbaud, not to mention The Joy of Gay Sex, co-authored with Charles Silverstein. But I am thinking especially of States of Desire: Travels in Gay America (1980), which records his visits to the diverse gay communities across the country, before they were united by the internet and representation in mainstream culture. It is of its time – often magnificently so, as in its description of the “San Francisco look”:

But it is also of its time in its repeated, inevitable attention to the brute facts of homophobia and how it crowds, limits and costs lives. The book, accidentally, became a vital record of gay life on the brink of Aids: the epidemic’s outsized impact in the US (which White went on to describe and protest) was a direct consequence of this indulged prejudice. But States of Desire doesn’t memorialise a lost Eden – “Gay life,” White said, “will never please an ideologue; it’s too untidy, too linked to the unpredictable vagaries of anarchic desire.” At one point in his travels, in Portland, he discovered “an unusual degree of integration with the straight community” worthy of remark: “A gay single or couple must deal with the family next door and the widow across the street; the proximity promotes a mixed gay-straight social life – parties, dinners, bridge games, a shared cup of coffee.” It’s a reminder of how amazingly far we’ve travelled. Edmund White was one of the people that brought us here – but he didn’t think integration and toleration, the right to marriage and a family, was an end-point. It was just one sight on the tour, and White showed us, with a proper absence of shame or embarrassment, many others rather more thrilling. Gay life shouldn’t ever mean one thing in particular; but what it can provide, as he wrote in States of Desire, “is some give in the social machine”.

Seán Hewitt

Edmund White was true giant of letters, the patron saint of queer literature. I can still remember, vividly, reading (in the wrong order), the books of the trilogy from A Boy’s Own Story to The Farewell Symphony, completely absorbed in White’s camp, biting humour, his name-dropping, his ability to capture self-delusion, fantasy, disappointment, anger, lust and romance in a heady, whirling voice. I remember saying to a friend, then, that I thought I could read him for ever.

White’s books were a fabulous, unending reel of anecdote and savage humour, attuned to the erotic impulse of writing, full of mincing queens, effeminate boys and brutal men: a fully stocked world of idolatry and abnegation. What stays with me, years later, is not only the biting social observation, but also the religious tenor of his mind, the affinities of his characters with the world of the sacred, of mystics and martyrs, which processed shame with such exuberance of feeling. I felt, in the company of his voice, educated in a secret, glamorous world, which was operatic in its emotion and brilliantly arch in its range of reference.

In his final book,The Loves of My Life, White proved himself an iconoclast to the end. Even the epigraph made me chuckle, because I could almost hear him chuckling to himself while setting it down: “Mae West hearing a bad actress auditioning for West’s hit comedy Sex: ‘She’s flushin’ my play down the terlet!’”. His honesty, even in his last years, was still enough to make you wince, still sharp enough to bring a shock of laughter, still melancholy and occasionally self-pitying enough to catch you off guard with all the many sadnesses of the world. I’m grateful that he left us so much work, and that the full, unadulterated sound of his voice is so potent, so convivial, so fresh and living on every page.