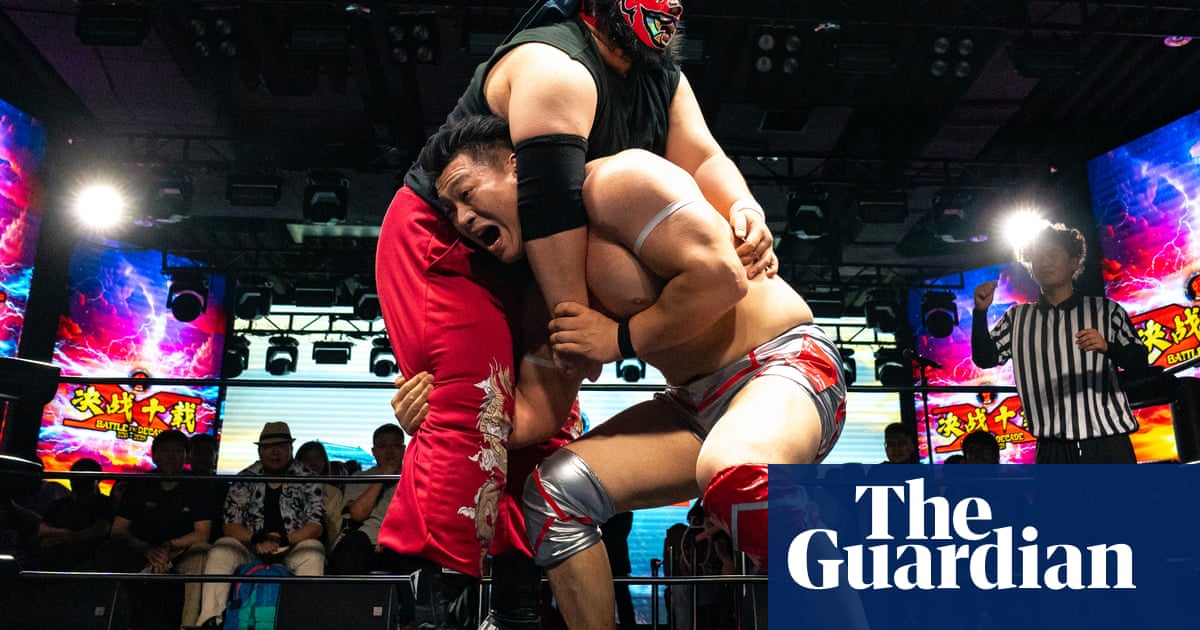

Rising from the ground with 73kg of writhing muscle on his shoulders, Wang Tao grimaced. The man whose legs were wrapped around his head was not giving up, pulling at Wang’s silver-tipped hair, dyed especially for the occasion.

But Wang knew what he had to do. Reaching up with one arm, he grasped his opponent’s neck, and pulled forwards, flinging him to the ground. Seconds later, Wang had him pinned to the floor for a three-count, and had successfully defended his title as Middle Kingdom Wrestling’s “Belt and Road” champion.

The crowd in Beijing went wild. “It was so much better than I expected,” said Wang, beaming with a post-match adrenaline rush. “The audience reaction was really, really good”.

Even Wang’s defeated opponent, Shaheen Alshehhi, was impressed. “You’re fucking awesome,” he , said after the match, inviting Wang to compete in Dubai.

Wang is the 25-year-old poster boy for an industry that has struggled for years to gain a foothold in China, despite a huge potential market and a culture that enjoys its own rich history of martial arts and professional fighting. Less than 10% of households with internet access watchpro-wrestling, according to a 2023 survey by S&P Global, a market intelligence company. For sports like basketball and football, the figure is over 50%.

Some in the industry hope that Wang could make the sport popular inChinathe way it is in America. Wang fell in love with wrestling after watching The Wrestler, an American movie starring Mickey Rourke, as a 15-year-old in rural Henan, one of China’s poorest provinces. Two years later he ran away from home to train at a wrestling camp hundreds of miles away.

Saturday’s event – to mark 10 years since the founding of Middle Kingdom Wrestling (MKW), one of China’s few pro-wrestling organisations – was the first time that the teenage runaway had ever been to Beijing.

He couldn’t sleep the night before with excitement. Now his brawn, showmanship, and the glitzy all-American spectacle of pro-wrestling is set to take the boy from the Chinese countryside from the middle kingdom to the Middle East. “If it wasn’t for wrestling, I probably wouldn’t even have a passport,” he said.

World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) launched in China in 2016, signing a streaming deal with a local platform and scouring China for homegrown talent. It is still pursuing an audience in China, and in 2020 reportedly signed a new partnership agreement with iQiyi, a Chinese streaming service. Events are also broadcast on some regional channels.

But the sport’s reach is limited because of a lack of official support and cultural understanding. Chinese authorities often confuse the choreographed events for actual fighting, or disapprove of the general air of anarchy that surrounds raucous matches.

The sports-or-entertainment quandary has baffled Chinese regulators, said Ho Ho Lun, a 37-year-old wrestling producer and performer who also competed on Saturday. Wrestling’s “theatrical elements” mean that sports authorities often punt responsibility for events to the entertainment bureau, while the entertainment bureau often wants to punt it straight back.

“So we’re in between, that’s our challenge,” Ho said. Later that night, he entered the ring at MKW’s sold-out event dressed in metallic green and silver trousers and a T-shirt emblazoned with a kung fu cartoon of himself performing a flying side kick.

It’s not just regulators who are confused. “Most Chinese people still think wrestling is fake compared to real fighting. They don’t understand it,” said Zhang, a 21-year-old student who travelled to Beijing from neighbouring Hebei to watch Saturday’s match. The winners in pro-wrestling matches are pre-decided, but fans insist that the athleticism and storytelling on display make it just as, if not more, compelling than other types of sport performances.

Adrian Gomez, a 37-year-old wrestling fanatic who founded MKW in 2015, is on a mission to change that. “You can’t just throw money at a market and expect it to work,” said Gomez, who hails from Arizona. “I think that WWE underestimated the fact that there still needs to be more connection with Chinese fans … they still want something that feels a little bit more authentic”.

In that vein, many of MKW’s wrestlers incorporate traditional Chinese elements into their characters. At Saturday’s soiree, one wrestler wore a long black Qing dynasty-style robe complete with a high mandarin collar and Chinese knot buttons. Another donned a red-and-gold Peking opera style mask, not dissimilar to the colourful wrestling face coverings worn by fans in the audience. Han Guangchen, a burly wrestler and film-maker from Shanghai, said videos that include elements of traditional Chinese martial arts do vastly better on social media.

But what Chinese wrestling really needs, according to the aficionados, is one big name. “Until we have one Jay Chou of wrestling that creates a big superstar, [going mainstream] will take some time,” said Ho, referring to the Taiwanese singer who is arguably the biggest Sinophone pop star in the world.

In 2016, as part of its China launch, WWE signed Wang Bin, a young Chinese athlete who was scouted in Japan. He caused a buzz as the American company’s first mainland Chinese wrestler, but he terminated his contract just two years later.

“American wrestling focuses more on performance,” Wang said at the time, while his first love, Japanese wrestling, “focuses more on fighting style and real skills”. Wang claimed to love both, but WWE deemed that he didn’t have the acting charisma necessary to excel in the idiosyncratic universe of American pro-wrestling.

Could Wang Tao be the answer? Now a full-time wrestler, he barely makes ends meet by competing in matches and making online content. But his reach is limited, with even the most popular videos attracting only about 1,000 viewers. Many of his friends have dropped out of the nascent industry because of the financial insecurity, he said. Although it hasn’t made him rich, it’s taken him to places he couldn’t have dreamed of a few years ago.

“When I get into the ring, with all the lights on and the crowds cheering, I feel that all the effort has been worth it,” he said.

MKW’s fans seem to agree, going wild for fist bumps and high fives when he stepped out of the ring. Laurel Burns, an American drama teacher in Beijing, was among the chanting and cheering crowd. “I was so excited to touch him,” she said.