William Blake may be known for seeing angels up in trees, for writing the alternative national anthem Jerusalem, and for his emblematic poem The Tyger. But his story is far more subversive and far queerer than cosy fables allow. It’s why Oscar Wilde hung a Blake nude on his college room wall. It’s why Blake became a lyric in a Pet Shop Boys song. And it’s why David Hockney is showing a Blake-inspired painting at his current exhibition in Paris.

When I lived in the East End of London, I’d walk over Blake’s grave in Bunhill Fields every day. It felt sort of disrespectful. Perhaps that’s why he has haunted me ever since. Years later, while trying to write a book about another artist, I got ill and very low. Suddenly, echoing one of his own visions, Blake came to me and said: “Well, how about it?” I felt I had to make amends for treading on his dreams. I’ve met many artists – Andy Warhol, Lucian Freud, Derek Jarman – but it is Blake whose hand I would love to have held and whose magical spirit I summon up in my new book. He even gave me my title: William Blake and the Sea Monsters of Love. (A friend has since pointed out that the title sounds suspiciously like a 1970s album by a certain starman from Mars).

I was writing about a man who had died a long time ago, yet who still seems alive and among us. Born in 1757, dying in 1827, Blake had perfect timing: not to be confined by Victorian mores, but to live in a looser, revolutionary age. He only ever sold 61 copies of his revolutionary “illuminated books” – which, for the first time, placed images and words together. Each would be worth £1m now. Blake might have died in poverty and obscurity, but that is exactly where his potential resides – as an unexploded but benevolent device. His posthumous influence lives on in flash-lit scenes – as if his afterlife were a movie being screened in front of us.

Cut to the 1820s and Blake’s young fans, called the Ancients, are led by Samuel Palmer, who bends to kiss the doorbell of their master’s lodgings as he passes by. They enact their Blakean cult in the Kentish countryside, swimming naked in a river and growing their hair long.

Jump forward to Manhattan in 1967 and Blake’s new disciples, Patti Smith andRobert Mapplethorpe, are reading his poetry to each other every night in their poverty. They’re obsessed. Mapplethorpe gets a job in an antiquarian bookstore and when a copy of Blake’s revolutionary America: A Prophecycomes in, he tears a page out and stuffs it down his trousers. Then, freaking out that he might be discovered, he goes to the toilet, rips it up and flushes it away. That evening, he confesses his sin to Smith, who celebrates his act, seeing it as a fabulous infection of the sewers of New York with their hero’s subversion.

Five years later, on the rocky coast of Dorset, Derek Jarman, deeply under Blake’s influence, recreates a Blakean scene for his first narrative Super 8 film. In flickering, saturated 70s colour, Andrew Logan poses as a sea god in the deconstructed dress he’d worn for his first Alternative Miss World that year. A half-naked young sailor floats in a rock pool. A young woman, wearing only a fishing net, plays the siren who lured him to his doom. That night, the crew meet Iris Murdoch in a nearby country house. She takes them up a hill to dance around a megalith in the moonlight. Murdoch cites Blake in a half a dozen of her queer-friendly novels, and discusses him with her lover, the gay liberation hero Brigid Brophy.

Flashback to Paris, 1958: Allen Ginsberg, citing Blake in his outrageously queer poem Howl,emulates his hero by reciting it in the nude outside Shakespeare and Company, the famous bookshop on the Left Bank. He’s accompanied by a besuited William S Burroughs, whose cut-up writing technique is heavily influenced by Blake’s proto-surrealist texts. In 1975, in the New Mexico desert, David Bowie will play a queer alien, singing and speaking Blake’s words, in the Nicolas Roeg film The Man Who Fell to Earth.

Like Shakespeare’s Prospero or Doctor Who, Blake has the power to appear anywhere, any time, rewriting his own fate through his art. That’s why one of Oscar Wilde’s young lovers, W Graham Robertson, was so inspired by Blake’s sensuality that he became his greatest champion, using a multimillion-pound fortune to buy up every work by Blake he could. Presenting them to the Tate 40 years later, Robertson saves Blake for the nation.

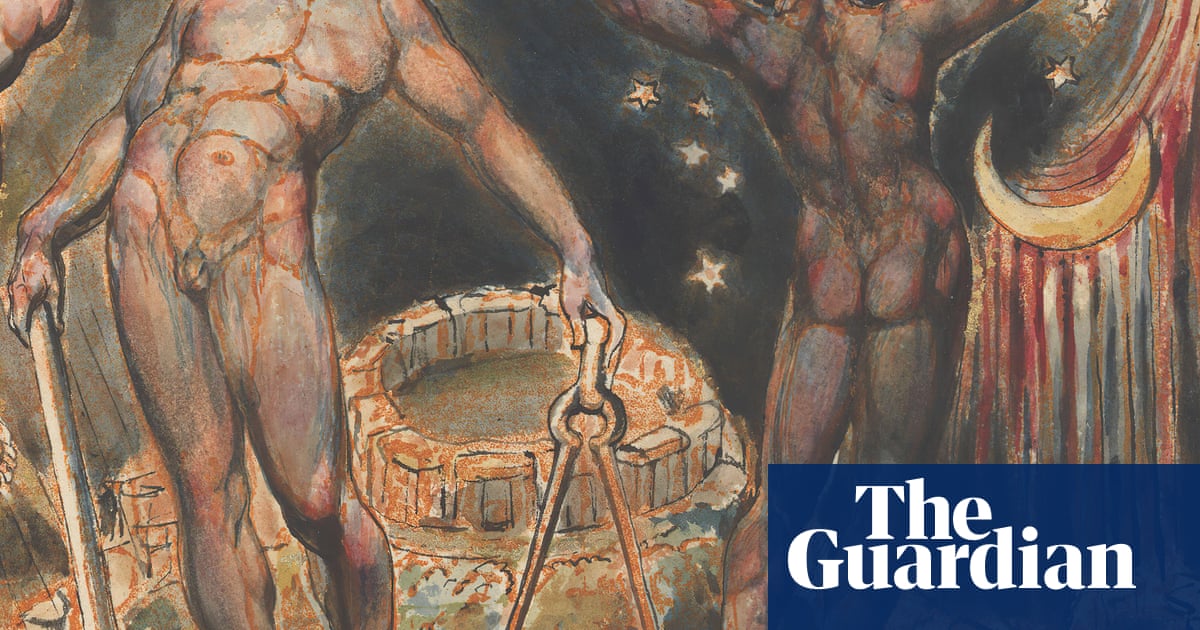

Yet Blake remains a secret, hiding in plain sight. In Milton, his astoundingly beautiful and prophetic book of 1804, he creates two images of male fellatio and a butt-naked Milton. They wouldn’t look out of place in a Mapplethorpe photograph. One reason Blake published his own work was to escape the censoring eye of the printer. It is this same transgression that powers James Joyce in 1920s Paris, as he deploys Blake’s queerness like a grenade in Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. Joyce’s Leopold Bloom changes sex in a lucid dream sequence, while British grenadiers drop their trousers to bugger each other as an emblem of the anti-imperialism Joyce and Blake shared.

In 1970s London, in their house that is as old as Blake, the artists Gilbert & George claim him as their saint. Like them, Blake would today be seen as one artist in two people. Misogynistic history has written his wife Catherine out of the story – but she shared his visions, printing and colouring them in. Then they’d spend the afternoon sitting naked in their backyard. “Come on in,” they’d tell visitors. “It’s only Adam and Eve, you know.”

Their neighbour is the Chevalier D’Eon, a former army officer who now performs fencing demonstrations in a black silk dress. D’Eon duly appears as Mr Femality in a witty salon skit written by Blake that today reads like a Joe Orton farce. Blake declared gender a mere earthly construction and agreed with Milton: “Spirits when they please / Can either Sex assume or both.”

Faced with this fantastical cast, I can only wonder at Blake’s alchemical effect. His large colour prints – such as a nude Isaac Newton with Michelangelo thighs sitting at the bottom of the sea – have a 3D texture that still defies explanation. He was trying to make reproducible paintings. Like Andy Warhol and Albrecht Dürer, Blake trained as commercial artist. He believed in the egalitarian power of art. He even proposed a 100ft tall image of a naked “Nelson Guiding Leviathan” to be set over the road to London like a Regency Angel of the North.

Shockingly modern, Blake burned with a fire that can’t be put out. His new Jerusalem was an achievable utopia, if only we shook off our “mind-forg’d manacles” – our prejudices about gender, sex, race and class. His art still inspires us as he shoots his arrows of desire from his bow of burning gold, standing there naked, bursting out of a rainbow. Blake’s new world is the one we long for, where we will all be gloriously free to love whoever and however we like.

William Blake and the Sea Monsters of Love is published by 4th Estate