There’s a visual quiz circulating on social media at the moment that promises to reveal your unresolved childhood trauma. Do you see an elephant first or a forest? A butterfly or an apple? Jungjin Lee’s exhibition, called Unseen,is in some ways an elevated version of that. The series of large, black-and-white landscape photographs – all made last year in Iceland – do not tell you anything about the times, or the place. Instead what you see depends on what is buried in you – threatening to open up that scary, unbidden “unseen”.

Lee, who lives in New York, is little known in the UK beyond her photobooks. This small show of 10 works is her first solo show in the UK in a 30-year career. Her background is important in deciphering these images. Her first artistic training was in the traditional calligraphic arts, as a child growing up in South Korea. Later she studied ceramics at Hongik University in Seoul, where artists such as Lee Bul were among her peers.

In the late 1980s, her first photography project followed an old man living on a remote Korean island, documenting his search for wild ginseng. In a decade, he had never found a single plant. But by the time Lee had finished the project, she realised what she had made was more a reflection of her own state of mind, and that she would never be a documentary photographer. She turned her back on the genre for good.

After moving to New York, she worked for a time as an assistant to Robert Frank. His attitude, rather than his style, influenced Lee, who was moved by the way he followed his instincts and interests. In the 1990s, she began to travel the US and make portraits of a decaying American landscape and its elements: the barren desert, the unforgiving wind, the endless debris. These clamouring landscapes were, and continue to be, portraits of the artist as rocks, trees, and thrashing waves. They come to be portraits of the viewer, too.

This new body of work was all made last year, in Iceland. Many contemporaries of Lee have made work about or with the Icelandic elements: Roni Horn, Ragnar Axelsson, Olafur Eliasson. Lee also responds to this aspect of the place. The specific topographies there provided Lee with what she needed: dramatic vistas capable of carrying the epic literary qualities of her work, the full range of human emotion. They are brooding, fearsome and roar with the supremacy of nature. The landscape, to Lee, is an expression of existential angst and metaphorical musings. Out there is the only subject capable of holding everything that’s in here, in us.

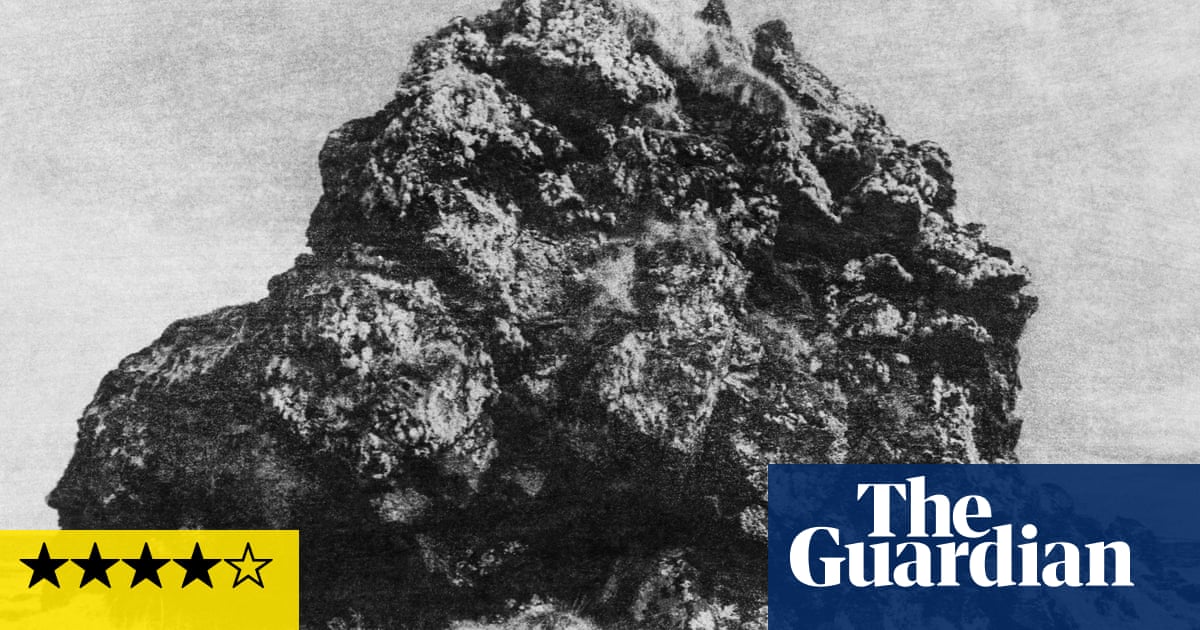

We are placed on an empty road that plunges into a dark abyss on the horizon (#83), or at the frothy seam of the sea and land (#55). You can almost feel the salty air slap your face in a portrait of an imposing rock standing resolute against the choppy water that whips up around it (#76). Its coarse and craggy surface seems to contain the history of the world. A smoky cloud descends on a blackened earth, its symbolism striking.

What you see, of course, is subjective. A mournful picture of two rocks (#49) shows them rising like tombstones from the sea, one large, jutting out, one tiny and intrepid, as if heading off into the distance. I make out the tender figures of a mother and child, the child forging ahead, falteringly, off into the unknown. I see Frank’s influence surfacing: the “humanity of the moment.” And the moment is uncertain.

You have to be a decent artist – even more so, working with a camera – to make a landscape picture interesting. Part of the brilliance of Lee’s work comes from her technical mastery, which reflects her journey as an artist, from the calligraphy of her childhood and the same raw approach to moulding the earth with her hands, adapted from ceramics.

Sign up toArt Weekly

Your weekly art world round-up, sketching out all the biggest stories, scandals and exhibitions

after newsletter promotion

It starts with a medium format Panoramic camera. She then brushes the negative with processing emulsion soaked on to delicatehanji, or Korean mulberry paper, and bathes them at a slightly higher temperature than is conventional for fixing. This optimises the mottled, etched textures. These hand-emulsified images are then transformed again, into digital images, at which point she tinkers with the contrasts and prints them again.

The brushstrokes to the surface are palpable and are as evocative Korean ink paintings – you can’t help but trace the influence of a pictorialist tradition that seeps unmistakably into Lee’s work. The knockout textures and the charcoal tones are aesthetically closer to drawings. At times the photograph seems to dissolve completely: in #10, a minimalist picture of a sloping mountain is stretched to abstraction, its suggestive black lines merely mimicking what was there.

Jungjin Lee: Unseen is atHuxley-Parlour Gallery, London, until 5 July