Tracey Moffatt’s triptych horror movie, Bedevil, opens with a story about a swamp haunted by the ghost of an American GI, who – legend has it – drove in one day and never emerged. The celebrated Indigenous artist brings this setting to life with a trick plucked from the expressionist playbook: using intentionally artificial sets to create jarring, surreal environments. Like the rest of the film, the effect is intoxicating.

The reeds, logs and water look authentic but behind the swamp the background glows with a bright synthetic green. It’s ghostly: partly real and partly not. A feeling that the air is thick and vaporous, twisted in all sorts of terrible ways, permeates each of the film’s three chapters, which are tonally similar but narratively connected only through the inclusion of supernatural elements.

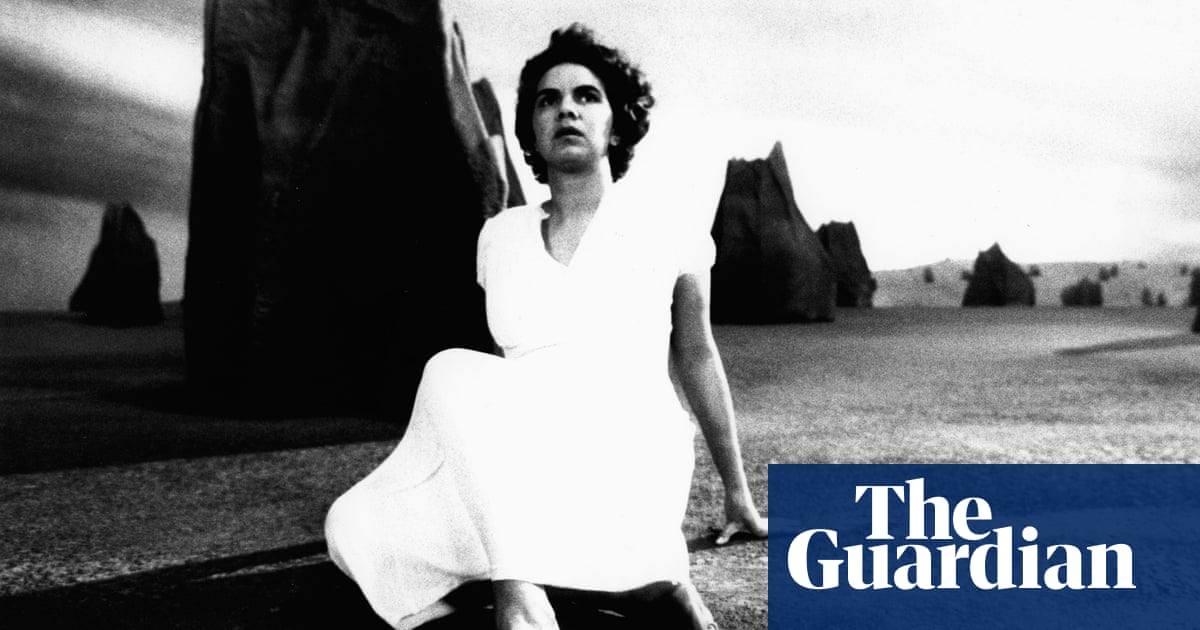

Each chapter features locations that are vividly hypnagogic, as if etched in the space between wakefulness and sleep. The second presents a house next to railway tracks used by ghost trains – and the spirit of a young girl. The landscape is dotted with rock-like formations that look unnaturally flimsy, almost like papier-mache. The final instalment follows a “doomed couple” who haunt a warehouse. With its creamy backdrops it evokes the paintings of the Australian artist Russell Drysdale, whom Moffatt has referenced in other works.

Sign up for the fun stuff with our rundown of must-reads, pop culture and tips for the weekend, every Saturday morning

Bedevil belongs to a long history of under-appreciated Australian films, neglected despite its milestones: it was the first feature film directed by an Australian Aboriginal woman. It received some international attention, screening at the 1993 Cannes film festival, and was championed by criticsincluding David Stratton. But there’s a feeling all these years later that this production hasn’t been given its dues.

To be fair, Bedevil was never going to be everybody’s cup of tea and it certainly doesn’t fit into a conventional box – it’s not the kind of genre flick that’s played at repertoire cinemas for midnight movie fans. Moffatt creates a kind of horror that has nothing to do with gore and jumpscares. It’s abstract, enigmatic and cerebral in all sorts of compelling ways, including its strange relationship with time. ANational Film and Sound Archive curatorsummarised it well: the film, perhaps alluding to the stories of the Dreaming, “challenges the linear time frame of Western storytelling in order to suggest the ongoing presence of entities interwoven throughout the landscape that supersede all human characters and players”.

We see this play out in various ways. In the first chapter, a seven-year-old Aboriginal boy, Rick (Kenneth Avery), falls into the swamp, gasping and reaching out for help. Soon we’re introduced to that boy as an adult man, played by the lateUncle Jack Charles, and then again as an 11-year-old, played by Ben Kennedy. Each timeline seems to blend, diffuse, liquefy; there’s no centre holding it together.

Further complicating things are dramatic changes in style and tone. At different points the film becomes a faux-documentary: Charles speaks to an unseen interviewer about the swamp, commenting on how he “hated that place” and bursting into uneasy laughter. Moffatt then cuts to a well-off white woman who reminisces about the “swamp business” before segueing into a bizarro sequence of cheerful music and sun-kissed images of sand, surf and community facilities, taking the tone of a tourism commercial.

Maintaining an ironic touch, Moffatt interrupts a menacing section of the second chapter with a kitschy outback segment like a cooking show involving the preparation of a wild pig (“marinated overnight with juniper berries, wine and fresh herbs”) and yabbies. It’s an audacious touch – so crazy it works. And it feeds into a feeling that part of the “horror” comes from never being entirely sure what the director is playing at.

Every time I watch this deeply peculiar film, its meaning slips through my fingers – yet I keep coming back, squinting through that thick, twisted air, trying to make sense of it.

Bedevil is streaming on SBS on Demand in Australia and Ovid in the US. For more recommendations of what to stream in Australia,click here