ATikTokvideo shows a young man fanning out a stack of $100 bills. A second flexes his designer clothes. Another man posts a video of himself dancing and wearing a heavy gold chain. They boast to their eager followers about their path to wealth.

“BM got me a new car,” states one caption on a video. “$5,000 in a few hours.”

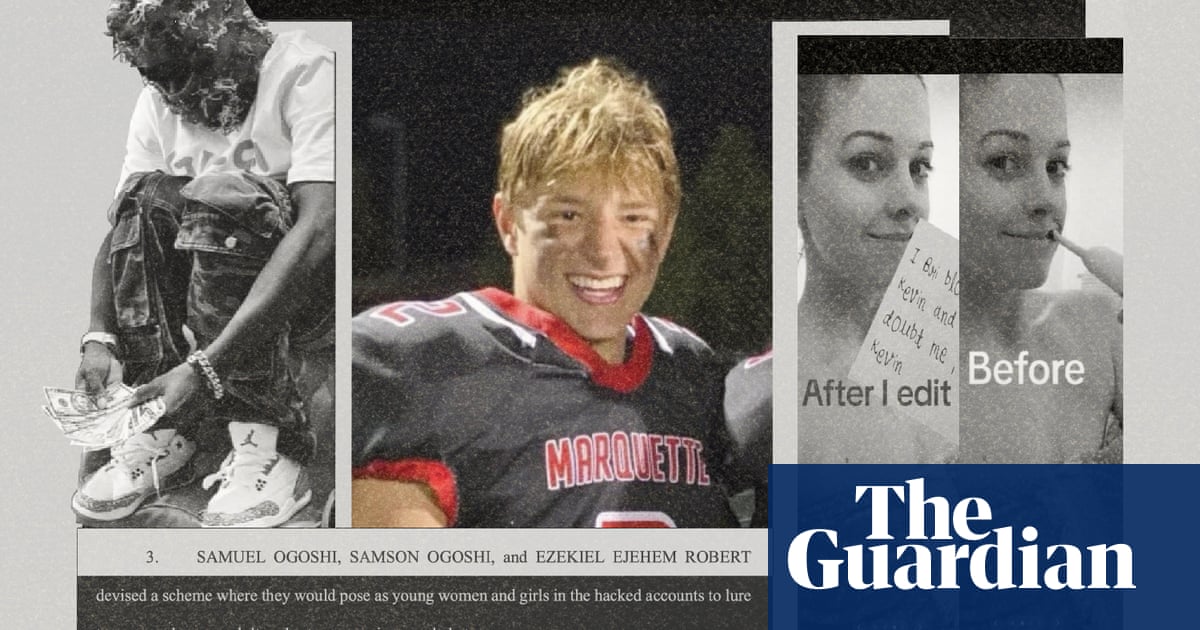

Unlike conventionalsocial mediainfluencers hawking travel, brands or recipes, their selling point is crime. The men are all based inNigeria, and their get-rich-quick scheme is blackmailing other social media users – usually based in the United States and other western nations – by posing as potential female romantic interests and tricking their victims into sending nude photos.

Then the threats of distributing the victim’s images and demands for money begin.

The proclaimed scammers call themselves the “BM Boys”. “BM” means blackmail, and hundreds of young men in west Africa are now engaging in these schemes. The videos flaunting their lifestyles, publicized onTikTokto hundreds and sometimes thousands of followers, draw admiration and ambition from other young men who follow them and plead to be included in their scams.

“Boss please can I come to learn [the] work please,” one follower commented on a popular BM Boy’s TikTok, which drew more than 2,000 likes. “I beg you [in] the name of God please. teach me work.”

Some of the BM Boys’ accounts have garnered several hundred thousand followers. The Guardian has identified 22 TikTok accounts run by self-proclaimed BM Boys and also interviewed a 24-year-old Nigerian man who has been working as a blackmailer for eight years. He claims to have collected nearly $100,000 from his victims during that time.

“For me, it’s an easy thing to do,” says the blackmailer, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss illegal activity. “Any day, any time, we are working on our phones because if you don’t work, you’re not going to eat.”

One of the primary demographics the BM Boys and others like them victimize is that of teenage boys in the US and elsewhere. In 2023 alone, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) received26,718 reportsof financial sextortion of minors, surging from 10,731 in 2022. Since 2021, at least 46 American teen boys have died by suicide after being targeted in sextortion blackmailing scams.

In 2024,Meta announcedit had removed 63,000 Instagram accounts it said were associated with Nigeria-based sextortionists. Despite the crackdown, Instagram remains the platform of choice for blackmailers to identify and engage with their targets, the blackmailer and human trafficking experts interviewed said. TikTok, meanwhile, is where BM Boys flaunt their success and recruit newcomers to their profession.

“Others are eager to participate and get in on this scam because they see how profitable it is. They show off the money and the gold, the luxurious clubs and travel that they’re doing,”says Paul Raffile, an expert in online exploitation. “They are using the platforms and this kind of influencer status in order to make money.”

By appearing to live an enviable lifestyle, established sextortionists recruit new scammers, known as “chatters”, to work for them. The bosses likely take a cut of their profits, said Raffile.

“These chatters are responsible for creating fake social media profiles, trawling the internet and making initial contact with potential victims,” said Raffile. “However, when it comes time to handle the actual transfer of funds – whether through Cash App, bitcoin wallets or other financial platforms – the boss steps in.”

A TikTok spokesperson said: “We design TikTok to be inhospitable for those intent on causing harm to teens and we do not tolerate any content or behavior promoting sextortion.”

A crucial part of the scheme involves building trust by convincing targets they are interacting with attractive women or girls who appear to be based in the same country. As a form of professional development for wannabe blackmailers, some BM Boys post “BM Updates” on their TikTok accounts, tips and education for their followers to learn or refine sextortion techniques.

“Millions of people want to get into it. If you don’t learn it, you’ll never be able to do it,” said the blackmailer, who frequently posts BM Updates to grow his following.

BM Updates include copies of scripts to follow, pictures of girls to use for imitation, tutorials on hacking Facebook accounts and advice on which virtual private networks (VPNs) to use to disguise that they are based in Nigeria to evade detection. There are instructions on composing angry voice notes to compel their victims to hand over payments and advice on where to find these targets, including dating sites and community pages.

To locate and connect with victims, perpetrators often engage in a tactic known as “bombing”, in which they mass-follow a large volume of individuals within specific online communities, such as people attending a school, following a sports team or keeping up with a celebrity. Blackmailers frequently share tips on which fanbases to target, pointing to followers of country music stars, Hollywood A-listers or popular television shows.

“They do that for two reasons. They will try to scam whoever accepts their follow request. The other reason they do this is it makes their fake accounts seem more legitimate because now when you get that friend request, that has 20 mutual friends in common,” said Raffile. “Sometimes they’ll say something like, ‘Oh, I saw you in my suggestions, or myInstagramsuggestions or people you may know.’”

To appear more convincing as Americans, BM Boys consume US news, sports and pop culture content obsessively, the blackmailer said.

Over thousands of attempts, the scripts and strategies have been refined into a high-pressure formula designed to lure victims into compromising situations quickly. In most cases, they’ll initiate the image exchange by sending a nude photo, often stolen from sites like OnlyFans, where sex workers create content, said Raffile.

The blackmailer’s next step is to demand between $500 and $3,000 in exchange for not distributing the photo to the victim’s social media contact, he said. To scare them, he’ll edit their photo on to a newspaper page or TV news show image.

Sign up toTechScape

A weekly dive in to how technology is shaping our lives

after newsletter promotion

“Sometimes I’ll call them and let them know they are talking to a man. When [the victim] sees his picture in the newspaper or TV news, he’ll be like, ‘Oh my god.’ He’s not going to block me,” he said. “I get my newspaper app and edit everything. I say, ‘It’s going to be seen on the fucking news on the TV.’”

Promoting the fruits of blackmail on TikTok does not come with compunction. The blackmailer interviewed said he is skeptical of reports that dozens of US teens have died by suicide after being targeted by sextortionists.

“I don’t feel guilty because this is not the main reason why they commit suicide. I’m not sure it’s the BM that makes the kids kill themselves,” said the blackmailer. “If somebody says they will kill themselves to me, I think they are kidding.”

He claims he was orphaned as a child when his mother died giving birth to one of his siblings, which leads him to treat sextortion as a job despite its emotional consequences.

“I feel nothing when I get the picture [from the victim]. I have to survive as a living thing,” he said.

The lack of remorse exhibited by BM Boys has been deeply traumatic for John DeMay and his family. In 2022, his son Jordan died by suicide at 17 after being targeted by three Nigerian men posing as a teenage girl on Instagram. Two of them, Samuel Ogoshi and his younger brother Samson Ogoshi, were extradited to the United States to face trial and are nowserving sentences of 17 years and six monthsin a federal prison.

When the judge handed down the sentences last September, he condemned the brothers for what he described as a “callous disregard for life”, referencing the fact that they continued their sextortion schemes even after learning that Jordan had taken his own life as a result of their actions.

“They fired back up and were right back at their same antics, with the exact same script, doing the exact same thing, the exact same way, knowing that Jordan killed himself,” said DeMay.

Experts say the balance between privacy and safety on children’s social media accounts must be different from that of adults, and that platforms should take stronger steps to protect minors.

“You’re dealing with a youth. You’re dealing with someone who will be a little more impulsive. So they’re going to make a decision, and maybe a warning isn’t enough. In that case, maybe you need to intervene in behavior because you’re dealing with a vulnerable population,” said Lloyd Richardson, director of technology at the Canadian Centre for Child Protection.

Meta has enacted a number of changes in recent years to protect its youngest users. In a statement, the company says its systems notifies teen users when they are corresponding with someone in another country, regardless of a VPN, and blurs nude images sent from or to an underage account.

A Meta spokesperson said in a statement: “Sextortion is a horrific crime. We work aggressively to fight it by removing networks of scammers, sharing information with other companies so they can take action too, and supporting law enforcement to prosecute these criminals.”

Since September, Instagram has made accounts it identifies as belonging to teens private by default, preventing people they’re not connected to from viewing their followers. However, once a teen accepts a follow request, that person gains access to the follower list. Making follower lists inaccessible even to approved followers would further protect teens from being targeted by sextortionists, as would hiding their profiles in search, said Raffile. He added: “It shouldn’t be as easy as going into the Yellow Pages and pointing, ‘Here’s a teenage boy, here’s a teenage girl,’”

DeMay said social media companies “have the capability of putting a lot of the safeguards that need to happen within the platforms to prevent this, but they’re choosing not to do it.”

In the US, you can call or text the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline on 988, chat on 988lifeline.org, or text HOME to 741741 to connect with a crisis counselor. In the UK, the youth suicide charity Papyrus can be contacted on 0800 068 4141 or email pat@papyrus-uk.org, and in the UK and Ireland Samaritans can be contacted on freephone 116 123, or email jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at befrienders.org