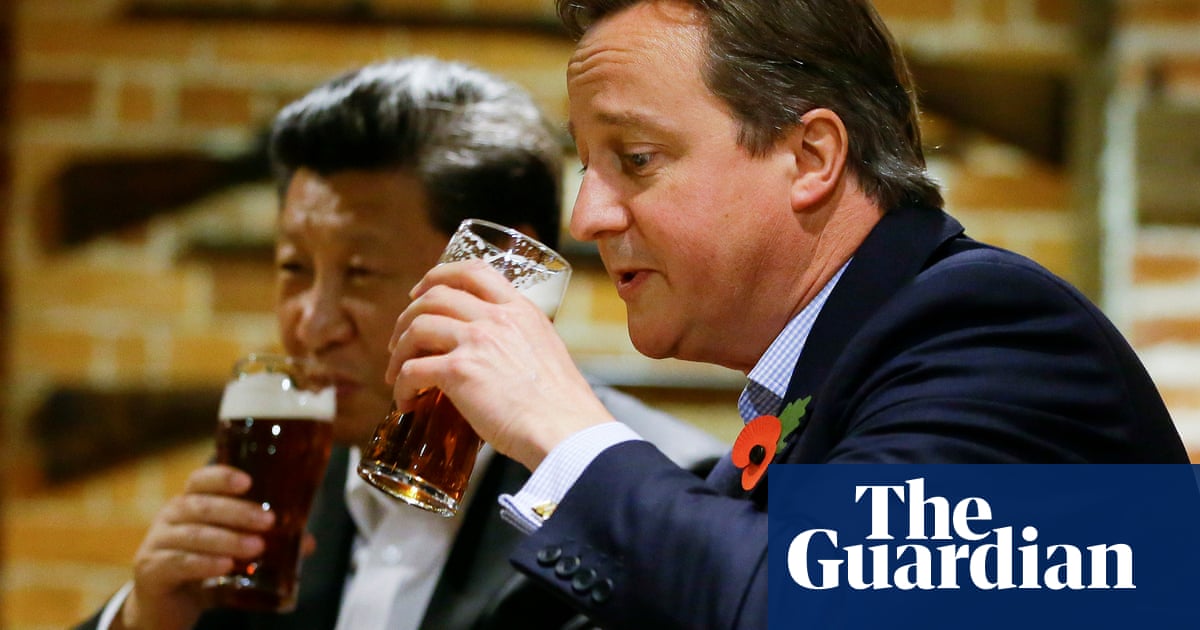

As even Donald Trump was forced to accept inscaling back his latest tariffs, China is just too big to ignore. And so it is, on a much smaller scale, that yet another UK government is doing several contradictory things at once when it comes to Beijing.This weekend brought a particularly resonant example. On the one hand, the business secretary, Jonathan Reynolds,was hintingthat British Steel’s Chinese owner, Jingye, was to blame for neglect – if not worse – over the fate of the threatened blast furnaces at Scunthorpe.Yet at the same time one of Reynolds’s own ministers, Douglas Alexander,was attendinga major consumer goods fair in Hainan, the tropical island on China’s southern tip, before holding trade-linked talks in Hong Kong, a visit that was not promoted in advance.Alexander was forced to mix some tougher politics with the trade, relaying what was termed “deep concern” at China’sdecision to barthe Liberal Democrat MP Wera Hobhouse from visiting her son and infant grandson in Hong Kong last week.For all that Foreign Office officials always insist that nothing fundamentally changes in the UK’s efforts to deal withChina, with endless talk of strategic decisions based on national self-interest, the reality is that the approach does very much vary by government, and not necessarily just when the ruling party switches.The most regularly highlighted contrast came under the Conservatives, when the “golden era” of Sino-UK ties, exemplified by David Cameron’scosy pub pintwith Xi Jinping, became notably more sceptical and even, during Liz Truss’s brief tenure, openly hostile.The stance taken by Labour governments has tended to be more consistent overall, but with a notable difference between the Blair-Brown era and that of Keir Starmer – and with the very obvious caveat that a lot changed in world affairs between 2010 and 2024.When Tony Blair took office, China was the world’s seventh-biggest economy and still four years away from joining the World Trade Organization, a move that led to an acceleration of the country’s already stellar rate of economic growth.View image in fullscreenExpanding trade was on the agenda in 2005 when Gordon Brown, the then UK chancellor, met the Chinese finance minister, Jin Renqing, in Beijing.Photograph: Jason Lee/ReutersThe period was thus – not unexpectedly – based around expanding trade with this new behemoth, a mood exemplified by a 2005 visit to Beijing and Shanghai by Gordon Brown in which the then chancellor marvelled at high-speed Maglev trains and personally gave every travelling journalist a book detailing this ongoing economic miracle.In retrospect, this approach, taken on by Cameron, risked the UK ignoring the parallel rise in China’s national security efforts. A2023 reportby the Commons intelligence and security committee castigated successive governments for allowing Beijing to invest heavily in vital UK infrastructure and gain influence by means as varied as spying and involvement in universities.Whether or not Jingye’s 2020decision to buythe stricken British Steel formed part of a Bejing-hatched strategic plan might never be known. But at the very least, the purchase of part of a totemic industry that once employed about 300,000 Britons by a company formed in 1988 in the heavily industrialised Chinese province of Hebei is a very tangible sign of how the global economy has changed.skip past newsletter promotionSign up toHeadlines UKFree newsletterGet the day’s headlines and highlights emailed direct to you every morningEnter your email addressSign upPrivacy Notice:Newsletters may contain info about charities, online ads, and content funded by outside parties. For more information see ourPrivacy Policy. We use Google reCaptcha to protect our website and the GooglePrivacy PolicyandTerms of Serviceapply.after newsletter promotionSince taking power, Starmer and his ministers have taken what is at least a more publicly emollient approach to China, with visits to the countryby David Lammy, the foreign secretary, and the chancellor, Rachel Reeves.A big part of this is focused, understandably, on growth, the government’s self-stated number one mission. But at the same time, as shown by the Jingye saga and Hobhouse’s plight, such efforts are never straightforward when Beijing is involved.Much more significant, and with the UK as a bit-part player, Trump’s US has begun a seeming fight to the death with China on tariffs, one that has not ended with the US president’s decision to exempt many electronic goods.With the globe reeling from Trump’s tactics and mistrustful of the US, China is ready to step in. The UK will be more wary than some. But yet again, it will be resigned to adjusting policy on the hoof.

Another UK government is doing contradictory things when it comes to China

TruthLens AI Suggested Headline:

"UK Government's Contradictory Approach to China Highlights Complex Trade and Political Dynamics"

TruthLens AI Summary

The UK's approach to China has become increasingly contradictory, reflecting the complexities of international relations and economic dependencies. Recently, Business Secretary Jonathan Reynolds criticized Jingye, the Chinese owner of British Steel, for neglecting the company's operations, particularly concerning the future of the Scunthorpe blast furnaces. This criticism contrasts sharply with the actions of Reynolds's minister, Douglas Alexander, who attended a significant consumer goods fair in Hainan, China, and engaged in trade discussions in Hong Kong. During these discussions, Alexander expressed 'deep concern' regarding China's decision to bar Liberal Democrat MP Wera Hobhouse from visiting her family in Hong Kong, highlighting the tension between political concerns and trade opportunities. Despite the UK government’s insistence on a consistent strategy toward China, the reality is that different administrations often adopt varying stances, influenced by both domestic politics and global events.

Historically, UK-China relations have fluctuated significantly, particularly between Conservative and Labour governments. Under the Conservatives, the relationship experienced a dramatic shift from the 'golden era' of engagement, characterized by David Cameron’s warm interactions with Xi Jinping, to a more skeptical and sometimes hostile approach, especially during Liz Truss's brief time in office. In contrast, Labour governments, particularly under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, initially pursued a strategy focused on expanding trade with China, which was then a rising economic power. However, this approach, while economically beneficial, overlooked China's growing influence in national security and infrastructure. Recent developments, such as Jingye's purchase of British Steel, underscore the changing dynamics of the global economy and the necessity for a more nuanced UK policy toward China. While the current Labour government under Keir Starmer aims for a more conciliatory approach to foster growth, it faces the challenge of navigating the complexities of trade and political sensitivities in a rapidly evolving geopolitical landscape.

TruthLens AI Analysis

The article highlights the contradictory actions of the UK government regarding its relationship with China. It reveals a complex dynamic where political rhetoric does not always align with practical engagements, indicating a lack of a cohesive strategy. This situation raises questions about the government's intentions and the broader implications for UK-China relations.

Contradictory Actions of the UK Government

The article illustrates a clear dissonance within the UK government, emphasizing how different officials are sending mixed signals regarding China. On one hand, the business secretary criticizes a Chinese company for neglecting its responsibilities, while on the other hand, a minister is engaging in trade talks in China. This juxtaposition suggests a struggle to balance diplomatic and economic interests, reflecting the larger global challenge of dealing with China.

Public Perception and Political Narrative

The narrative suggests that the government is attempting to maintain a strong stance against China while simultaneously engaging in trade relations. This duality may create confusion among the public, leading them to question the government's commitment to its stated values versus economic necessities. The article may aim to shape public perception about the inconsistency in government policy, highlighting a need for clarity and coherence in foreign policy.

Potential Omissions and Hidden Agendas

While the article focuses on the contradictions, it may also imply that there are underlying agendas at play. The emphasis on trade discussions in China could overshadow concerns about human rights or political freedoms, which could be a strategic choice to avoid negative backlash against economic partnerships. Thus, the article raises the possibility that not all aspects of the UK-China relationship are being fully disclosed to the public.

Manipulative Elements and Trustworthiness

The article's presentation could be seen as somewhat manipulative, as it emphasizes contradictions without offering a comprehensive view of the complexities of international relations. This approach may lead readers to feel skeptical about the government's sincerity. However, the core facts presented appear to be accurate, based on the actions described, making the overall reliability of the news moderate yet potentially biased towards highlighting inconsistencies.

Impact on Society and Politics

The implications of such a narrative are significant. If public trust in the government wanes due to perceived contradictions, it could influence voter behavior and political engagement. Moreover, the focus on trade relations with China, juxtaposed with criticisms, may lead to calls for a more principled stance on international human rights issues, affecting the political landscape.

Audience and Support Base

This piece may resonate more with audiences that are critical of government actions and those who prioritize ethical considerations in foreign policy. It targets individuals who are concerned about the implications of trade relationships with countries like China, particularly in light of human rights abuses and authoritarian governance.

Market Reactions and Economic Consequences

In terms of market impact, the article could influence investor sentiment toward UK companies involved in trade with China. Stocks of companies like British Steel may be affected if concerns about their ownership and operational management persist. Additionally, the broader implications for trade relations with China could impact sectors reliant on Chinese imports or exports.

Geopolitical Relevance

The article touches upon important themes in the context of global power dynamics, particularly as nations navigate their relationships with China amidst rising tensions. As the UK reassesses its position, this news aligns with ongoing discussions about balancing economic interests with geopolitical considerations. The tone and content of this news piece suggest an analytical approach rather than a purely objective report. The focus on contradictions and political commentary indicates an intent to provoke thought and discussion around UK-China relations. Overall, while the article presents factual information, its framing could lead to interpretations that align more with criticism of the UK government's approach.