Alarge puddle of water and thickets of weeds cover a vacant lot in Bethesda,Maryland. A towering apartment complex overshadows the cracked asphalt, but Marsha Coleman-Adebayo is most concerned about what – and who – lies beneath.

The nearly two-acre site in theWashington DCsuburb covers the historic Moses Macedonia African Cemetery and another burial ground forenslaved people, with the oldest portion dating back to at least themid-1800s. Hundreds of bones found there may be the remains of enslaved people and their descendants, whilemore bodiesmay lie under the parking lot of the Westwood Tower apartment complex.

But like many resting grounds for Black Americans, its preservation is jeopardized by loss of its original community through gentrification and, now, encroaching development. And despite a recent federal law to protect Black cemeteries, they are vulnerable to neglect and eventual destruction.

Coleman-Adebayo is the president of the Bethesda African Cemetery Coalition (Bacc), which since 2016 has aimed to save the site from further development and return the land to the descendant community. It plans to eventually erect a museum or monument there. She first learned about the cemetery a year earlier, when she attended a joint county park and planning commission meeting where she met a longtime resident who recalled playing in the long-forgotten cemetery as a child.

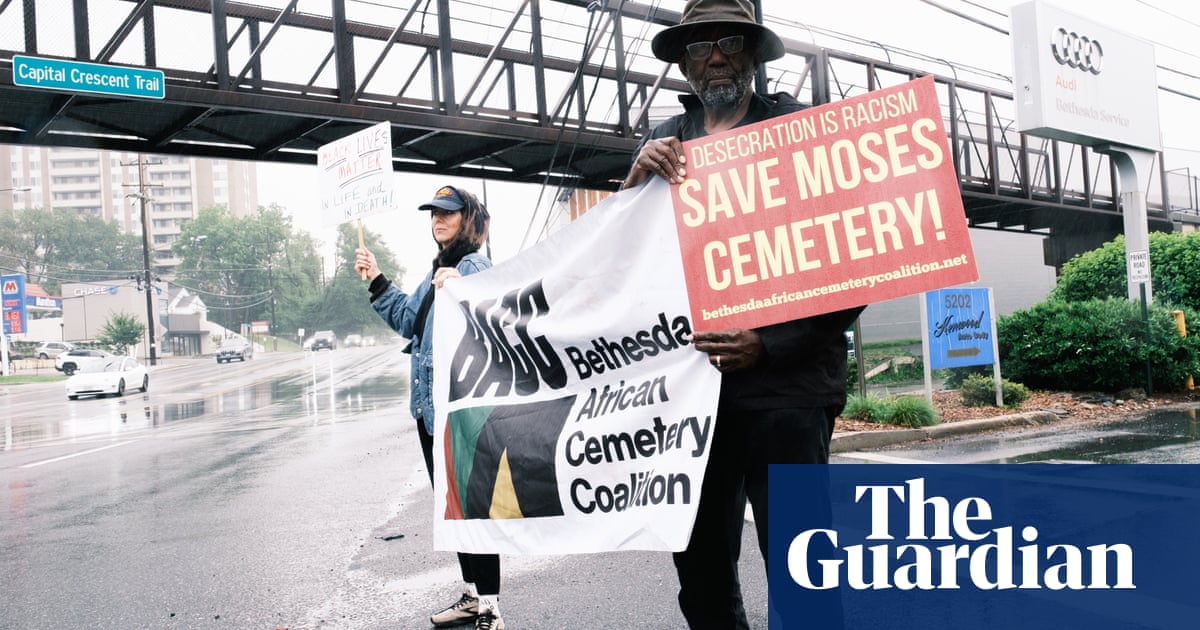

Every week, Bacc members stage a protest at the McDonald’s parking lot next door. Separated into several parcels, the portion of the burial ground that was leveled for Westwood Tower’s parking lot in the 1960s is now owned by the housing opportunities commission of Montgomery county (HOC), which provides low-income housing. Another part of the cemetery, owned by the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, is overgrown with vegetation. A third section, held by the self-storage developer 1784 Capital Holdings, has incited ongoing Bacc protests since construction for a storage facility began in 2017. The burial site has turned into a legal battleground as the coalition has spent several years in court fighting the HOC.

The dispute at Moses Macedonia African Cemetery serves to “open up the conversation about what a major problem that African Americans are having at these sites,” said Michael Blakey, a National Endowment for the Humanities professor of anthropology, Africana studies and American studies at the College of William and Mary. For over a decade beginning in the 1990s, Blakey directed the African Burial Ground Project at Howard University, where he and a team of researchers analyzed more than400 skeletal remainsof enslaved and free Africans interred in New York City in the 17th and 18th centuries. His work was guided by the descendants’ questions about their ancestors. “Even when they assert their rights as a descendent community, it’s a wrestling match with bureaucracies, sometimes even anthropologists,” he said.

Burial rites reveal a society’s values in life and in death, Blakey added. “The desecration of Black cemeteries is a reflection, whether in slavery or in current development projects … of the lack of empathy with African Americans as complete human beings,” he said. “And African Americans, from slavery to the present, have defended those cemeteries with sure knowledge of their full humanity and an insistence upon their dignity.”

The Moses Macedonia African Cemetery in Bethesda; the Evergreen Cemetery in St Petersburg, Florida; and the Buena Vista plantation’s burial ground in St James parish,Louisiana, demonstrate ongoing fights to preserve Black burial sites in the face of development throughout the US. Amid the scant oversight of Black cemeteries, a growing movement of descendant communities and their allies are protecting the grounds by documenting their existence, protesting development and performing genealogical research on the buried.

On a rainy May evening, Coleman-Adebayo held a large white sign listing violations of what she considers a sacred space. “Even a dog cemetery would not be treated like this,” she told the Guardian. As anEnvironmental Protection Agency whistleblowerwho sounded the alarm on US vanadium mining in South Africa in the 1990s, Coleman-Adebayo has a long history of activism. She also helped spearhead theNo Fear Act, which discourages retaliation and discrimination in the federal government.

Bacc contends that, during a 2020 excavation, a dump truck took earth from the cemetery to a landfill. Members followed and say they found 30 funerary objects including pieces of cloth, a hair pick and a tombstone. They have also demanded the return of200 bonesheld by a consulting firm in a Gainesville, Virginia, warehouse to no avail. In August, a circuit court will hear a case in which Bacc and several other plaintiffs are requesting$40min compensation from the HOC for emotional damage and to build a museum.

Coleman-Adebayo looked somberly at the scaffolding erected by self-storage developer 1784 Capital Holdings. “Look what they’re building here on the bodies of African people,” Coleman-Adebayo said. “How did they die? How did they live? What happened to them? And the county could care less because they’re Black.”

The HOC and 1784 Capital Holdings did not respond to requests for comment by publication date.

The River Road community, an African American enclave linked to the cemetery, was a once bustling district withBlack land ownership, a school and the Macedonia Baptist church, whichopened in 1920. By the 1950s and 1960s,the area was zoned for commercial use. Now, Coleman-Adebayo’s husband, the Rev Olusegun Adebayo, chairs Bacc’s board and pastors the church, the only surviving institution of the historically Black community.

Black cemeteries have long been threatened. In the 18th century, Blakey said, Black cemeteries were also used to dump waste from pottery factories and tanneries. Historian and anthropologist Lynn Rainville, who has researched Black cemeteries for 20 years, noted that Black bodies were dug up to use as cadavers for 19th-century medical research. But robbers rarely disinterred Black bodies to steal objects or jewelry, as they frequently did to Indigenous burial grounds. After the civil war, Black cemeteries were usually placed in areas with cheaper property values, which later became prime real estate for developers. Some Black cemeteries were also neglected following the great migration of the early 20th century, when 6 million Black people moved from the south to other parts of the US for economic opportunity and to escape racism. As a result, many Black people moved away from their ancestors’ graves.

“The Black living communities have long since been forced out of there because of high taxes, high property values,” Rainville said. “The cemetery is the last of what’s left, and then it is at greatest risk.”

The development at the Moses Macedonia African Cemetery shows that American society values certain bodies over others, said Rainville: “If 2,000 prominent, wealthy people in Bethesda, Maryland, came forward and said, ‘Hey, these are my relatives,’ it would have been stopped by now. No one’s digging up Thomas Jefferson, for example. There is a hierarchy of what and when in American society is considered OK to move.”

During his travels and work throughout the world, Blakey found that development is the paramount threat to Black cemeteries. He recalled discussing with a Howard University colleague in the 1970s about how Black internment sites, he said, “were the places developers were said to be most fond of because they knew they could dispose of them with greater ease”.

A federal law similar to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), which requires institutions and federal agencies to return human remains and artifacts to their descendant Indigenous tribes, does not exist for Black Americans, said Rainville. Signed into law in the 1990s, the NAGPRA came after hundreds of years of the desecration of Native American graves.

In recent years, a national movement has emerged to protect Black graves by creating a law that parallels the NAGPRA. Enacted into law in 2022, theAfrican American Burial Grounds Preservation Actauthorized the National Park Service to fund federal and state agencies, as well as non-profits’ efforts, to research and preserve Black cemeteries. But the National Park Service told the Guardian that it has not awarded any grants so far, since Congress has not allocated money to the program.

Seeing a need to prevent the erasure of African American burial grounds in her local community, University of South Florida anthropology chair and professor Antoinette Jackson created theBlack Cemetery Network, a database of internment sites throughout the US. Of the 193 cemeteries listed on the site, Jackson said that up to 70% of them face preservation challenges, including threats from development, legal battles or lack of resources.

A lack of Black political power in the early 20th century fueled neglect and subsequent loss of cemeteries through tax sales, she added. “It was by design, because many of the ones that were lost were in what became a desirable area for that time,” Jackson said. “Up until the 1965 Civil Rights Act, [Black political] representation wasn’t there in many of these governmental agencies, committees and commissions. So, often, there was no one to defend them, and they were easily given away or changed hands without people really being aware.”

She cites a2021 Florida lawthat protects abandoned African American cemeteries as a potential model for other states. The law created ataskforcethat identified and researched cemeteries, and led an advisory council that provides recommendations for their preservation. Research and academic institutions, non-profits and local governmental organizations may also apply fora grant of up to $50,000to conduct historical and genealogical research, or to restore and maintain abandoned cemeteries.

Jacksonreceivedthat state grant to find the descendants of theEvergreen Cemetery– one of three graveyards buried under Interstate 175 and Tropicana Field, a St Petersburg stadium being considered forredevelopment. Through Jackson’s work, St Petersburg city council member Corey Givens Jr learned that his great-great-great-uncle was buried in the historically Black cemetery.

Givens wants the city to conduct a ground-penetrating radar survey of the site to see if any burials remain there. That was done forOaklawn Cemetery, where mostly white people were interred and at least10 possible graveswere recently found. But the Florida department of transportation, which owns the property where Evergreen and another Black cemetery,Moffett, are located,has refusedto allow a survey.

Givens hopes that the descendants of people interred in Evergreen and Moffett will have a say in the future of the site. “Do we just want to leave these bodies there? Or do we feel like we want to spend tax dollars and move these bodies elsewhere?” Givens told the Guardian. “I really want the community to be in charge of this conversation. I want them to lead it because I don’t trust the same governing body that said ‘out of sight, out of mind’.”

At the site of the Buena Vista plantation in St James parish, Louisiana,the Louisiana Bucket BrigadeandInclusive Louisianaenvironmental justice groups are using genealogical research of enslaved people buried on the land to fight the construction of a petrochemical facility.

The Louisiana Bucket Brigade and Inclusive Louisiana learned through a public records request of the Louisiana division of archaeology’s emails that a graveyard for enslaved Africans existed on the land where the Taiwanese company Formosa Plastics planned to construct a$9.4bn facility. Lenora Gobert, the Louisiana Bucket Brigade’s genealogist, spent years researching the mortgage and conveyance records from plantation owner Benjamin Winchester to learn the names of the enslaved people buried there between 1820 and 1861. In 2024, the non-profitreleased a reportdetailing the lives of five enslaved people ages nine to 31. Among them was 18-year-old Betsy, who was buried on the plantation’s edge and mortgaged by the Winchesters at least seven times in life and death.

Anne Rolfes, the Louisiana Bucket Brigade’s director, hopes that evidence of the graveyard will help further stall or cancel the development. She would like descendant communities to have a say in how the area is memorialized and programming that honors the area’s history.

“How about we just stop all this petrochemical expansion? It destroys these really sacred places, and it’s not economic development. It’s destruction, massive disruption and illness,” Rolfes told the Guardian. “So let’s instead center this. That would preserve the communities. It would provide so many more jobs. It would be deeply meaningful. It would be a beacon to the rest of the country.”

Meanwhile, in Bethesda, about100 peopleattended Bacc’s “rebellion” on 19 June, Coleman-Adebayo said, during which the group featured poetry, dancing and speakers who talked about the struggle to protect the cemetery.Bacc also protestedat the county’sJuneteenth eventon 21 June.

At Bacc’s Juneteenth event, member Joann SM Bagnerise received an award for her outstanding advocacy. Bagnerise, an 87-year-old from Dumfries, Virginia, has traveled over an hour each way to join the coalition’s weekly protests for several years. During a recent May protest, she sat in a chair under an umbrella and said: “The desecration of hallowed grounds is un-American.” The high-rise apartment at the center of the dispute towered behind her. “There are young teenagers buried here,” she said. “There are mothers and fathers.”